In this series

Is America a “Christian nation”? When we worry about the direction our nation is heading, or celebrate when we see as a positive religious turn in American culture or politics, we are making assumptions about our own religious background as a country. Most of these assumptions are based on civics classes we took in primary and secondary school. While our assumptions claim a historical basis, there are a number of misunderstandings, some subtle and some overt, that Americans often have about their religious history. Here are five of the most common:

America's Religious History: Faith, Politics, and the Shaping of a Nation

HarperCollins

320 pages

$13.64

1. Religion had little to do with the American Revolution.

The American national Congress during the Revolutionary War was ostensibly secular, but it sometimes issued proclamations for prayer, fasting, and thanksgiving that employed detailed theological language. Whereas the Declaration of Independence had used generic theistic language about the creator and “nature’s God,” a 1777 thanksgiving proclamation recommended that Americans confess their sins and pray that God “through the merits of Jesus Christ” would forgive them. They further enjoined Americans to pray for the “enlargement of that kingdom which consisteth ‘in righteousness, peace and joy in the Holy Ghost’ [Romans 14:17].”

Some have argued that the Declaration of Independence illustrates the “secular character of the Revolution.” The Declaration was specific about the action of God in creation, however. A theistic basis for the equality of humankind was broadly shared by Americans in 1776. Thomas Jefferson did not let his skepticism about Christian doctrine preclude the use of a theistic argument to persuade Americans. Jefferson was hardly an atheist, in any case. Like virtually all Americans, he assumed that God, in some way and at some time in the past, had created the world and humankind.

The Virginia Declaration of Rights, which had been adopted just weeks before the Declaration of Independence, had spoken blandly of how “all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights.” Drawing on the naturalistic theory of government crafted by John Locke, this first section of the Virginia Declaration made no explicit reference to God. Yet when Jefferson and his drafting committee wrote the Declaration of Independence, they made the action of God in creation much clearer. “All men are created equal,” and “they are endowed by their Creator,” Jefferson wrote. The Declaration was not explicitly Christian, but its theism was intentional. This is not to say that the founding documents are uniformly theistic. The Constitution hardly referred to God at all, save for a paltry reference to the “Year of our Lord” 1787.

2. Religious conflict and violence is worse today than it has ever been before.

Religious vitality in America has always existed alongside religious violence. To cite just one example, in 1782, during the latter years of the Revolutionary War, an American militia in the Ohio territory attacked Moravian mission stations in Native American communities along the Muskingum River. The Moravian Delaware Indians were pacifists, having embraced the German-background Moravian missionaries and their teachings about Jesus, the Prince of Peace. The interethnic mission station attracted unwanted attention from many of its neighbors. The Delaware converts sought to allay the suspicions of hostile forces surrounding them—including non-Christian Indians, American Patriots, and British authorities—by employing Christian charity. They shared what food they had with their neighbors, even in times of scarcity.

American militiamen, however, were certain that the Moravian station at Gnadenhütten (“tents of grace”) was a staging ground for Indian attacks on frontier settlers. Driven by genocidal rage against all Indians, Christians or otherwise, the white volunteers imprisoned and methodically murdered almost a hundred Moravian Delaware men, women, and children around Gnadenhütten, even as the doomed converts were reportedly “praying, singing, and kissing.”

The stage was set for the Gnadenhütten massacre by a convergence of white Americans’ hatred for Indians, the violence of the American Revolution, and the earnest missionary labors of the Moravians. Not all religious violence in American history has been as grotesque as that at Gnadenhütten. Sometimes the violence has taken rhetorical, legal, or other forms (what we generically would call religious “conflict”). Unfortunately, religious fervor and religious viciousness are not only part of a distant colonial American past.

Indeed, episodes of religiously tinged mass murder have become common in the years since the September 11, 2001 jihadist attacks in New York and Washington, DC. Mass shootings have become almost a routine feature of American life, often targeting places of worship. These include shootings at congregations such as the Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin (2012), the First Baptist Church of Sutherland Springs, Texas (2017), and the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh (2018). The shooting at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015 was unusual only in the sense that the congregation had endured a similar paroxysm of violence almost two centuries earlier, when an alleged slave rebellion led by Denmark Vesey led to the execution of dozens of African American Charlestonians and the burning of the church building.

Religion has been a source of hope for many Americans and a focus of hate for others. The vitality of faith has endured, even in the face of murderous animosity, especially toward religious and ethnic minorities.

3. The concept of religious liberty primarily grew out of Enlightenment theory.

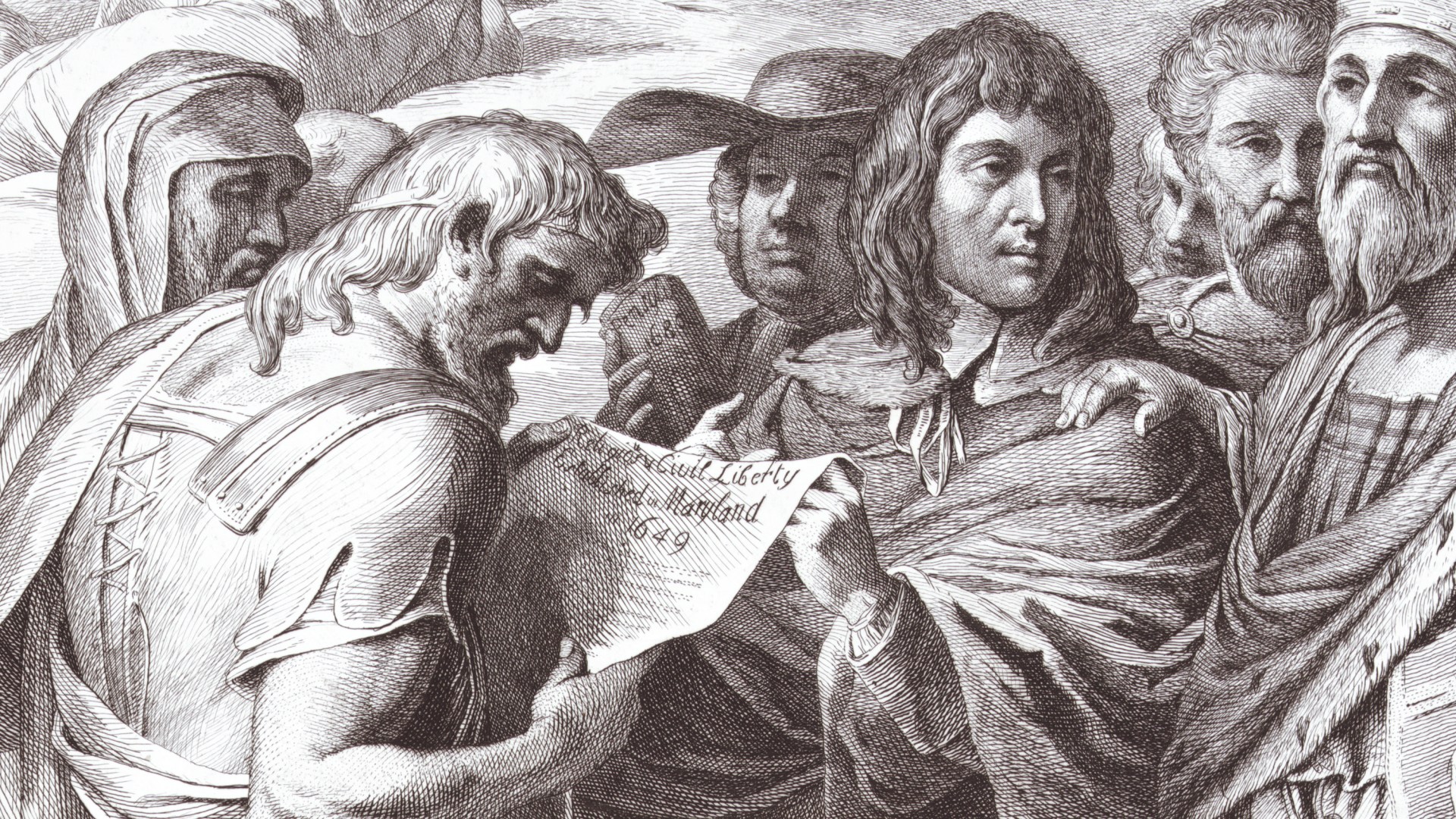

Only the colonies of Pennsylvania and Rhode Island offered religious freedom in any way resembling its modern meaning. The great religious diversity of many colonies caused conflict and elicited calls for religious liberty. These calls included Maryland’s 1649 Act Concerning Religion, which promised the “free exercise” of religion for all Christians. Nevertheless, well into the Revolutionary era many of the established churches still treated dissenters with contempt, if not outright violence.

The Great Awakening of the 1740s generated a new wave of activism for religious liberty. Especially in New England, where the Congregationalist Church was established, evangelical Separates (those who started illicit separate meetings) and Baptists called on authorities to allow them to worship God in freedom. In Connecticut in 1748, a group of Separates petitioned the colonial legislature for religious liberty, calling freedom of conscience an “unalienable right” upon which the government should not intrude. Connecticut refused to act upon the Separates’ plea.

Baptists were the most consistent advocates for religious liberty as the Revolution approached. As Separate Baptist churches and missionaries spread throughout the South, they fell under increasing persecution. In Virginia, where the Anglican Church was established, political and religious authorities took an especially harsh approach to dissenters. They put a number of legal requirements in place that made it difficult for dissenters to build churches and get preaching licenses. Many Baptists simply ignored these requirements. They suffered accordingly. Dozens of Baptist preachers were put in jail in Virginia in the 1760s and 1770s. One of them, James Ireland, was arrested for illegal preaching in Culpeper, Virginia, and was mercilessly hounded by anti-Baptist thugs. Ireland’s supporters followed him to the jail, and Ireland tried to keep preaching to them through a window. Ireland’s antagonists beat up his supporters, and some even urinated on him through the window as he attempted to keep speaking.

The plight of the Baptists drew the sympathy of nonevangelical leaders such as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Madison and Jefferson already believed in religious liberty as an intellectual precept. Theorists associated with the Enlightenment, such as England’s John Locke, had argued for religious toleration for Protestant dissenters. The Enlightenment, as a catch-all term, can broadly refer to an emphasis on human rationality, scientific discovery, and naturalistic philosophy in the late 1600s and the 1700s. The abuse of Baptists and other dissenters hardened Madison and Jefferson’s resolve to achieve disestablishment, or the end of state-supported religion. Madison deplored the persecution of dissenters. In a 1774 letter, he lamented the “diabolical hell conceived principle of persecution” raging at the time in Virginia. He asked his correspondent to “pray for Liberty of Conscience to revive among us.”

4. Christians in early America didn’t have to contend with skepticism and heterodox theology.

The early decades of the 1800s saw huge religious growth, diversification, and conflict. The period of disestablishment of the state churches also afforded a more prominent role for religious skeptics. Surging Christian commitment in the Second Great Awakening actually fed the skeptical backlash. But the story of doubt about traditional faith was an even older one. In the colonial era, some Americans expressed serious questions about traditional Christian theology, especially about Calvinism.

Some of the earliest skeptical views, particularly universalism, emerged from Calvinism. Universalists espoused the notion that God would eventually save all people through Christ. If God chose some (the elect) for salvation, why would he not choose everyone? Charles Chauncy, Jonathan Edwards’s key adversary during the First Great Awakening, became one of America’s first universalists. Chauncy secretly cultivated universalist views for years before finally going public in the 1780s. He even coined a code term (“the pudding”) for universalism because it was so controversial. Chauncy posited that since God was preeminently benevolent, he would not “bring mankind into existence, unless he intended to make them finally happy.”

Deism was less an outgrowth of Calvinism than a rejection of it. We can see this most obviously in the case of Benjamin Franklin, who by his teen years had come to doubt his Puritan parents’ faith. His father gave anti-Deistic tracts to the bright boy, but Franklin found the Deists’ arguments more convincing than traditional Christians’ arguments against Deism. Thus, as Franklin wrote in his wildly popular Autobiography, he became a “thorough Deist.” To Franklin, Deism meant downplaying doctrine and focusing on virtue and benevolent service as the essence of Christianity. He also doubted the divinity of Christ and the reliability of the Bible.

Deism was fashionable among educated men in the American Revolutionary era and was overrepresented among the Founding Fathers. Thomas Jefferson was a more strident Deist than Franklin, though Jefferson mostly kept his skepticism quiet until his political career had ended. Jefferson did consider himself a Christian, but he only revered Jesus as a moral teacher, not the Son of God.

Jefferson was convinced that Jesus’s followers had imposed the claims of divinity on him after he died. This accounts for the so-called Jefferson Bible, which was Jefferson’s multilanguage edition of the Gospels. Jefferson used a penknife to cut out sections of the Gospels that he found implausible, especially a number of the miracles attributed to Jesus. In the last verse of the Jefferson Bible, Jesus’s disciples “rolled a great stone to the door of the sepulchre, and departed.” There was no resurrection in Jefferson’s account.

5. The connection between white evangelicals and the Republican Party began with the Moral Majority.

Although President Dwight Eisenhower was not especially devout, he wanted to reenergize American civil spirituality. The evangelist Billy Graham helped him do that. Graham assured Eisenhower, whom he had urged to run for president in 1952, that as president the general could “do more to inspire the American people to a more spiritual way of life than any other man alive.” For Graham, Eisenhower, and their supporters, the Judeo-Christian tradition represented a shield against the atheistic menace of communism. The term Judeo-Christian first became popular during the period. Although Graham’s preaching was as explicitly Christian as any minister’s, the civil religion favored by Eisenhower was generically theistic, not Christian. Anticommunist civil spirituality reached its height in the mid-1950s when Congress added the phrase “one nation under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance and made “In God We Trust” the national motto.

Untold thousands of people around the world became born-again Christians due to Billy Graham’s preaching and that of other evangelical and Pentecostal ministers during the era. But in retrospect one of the most salient developments associated with Graham’s work and the “neo-evangelicals” is their growing linkage with politics and the Republican Party. Evangelicals had been engaged in politics before the 1950s, of course, but Graham facilitated the transformation by which American evangelicals—especially white evangelicals—would become known primarily for their political behavior.

To Graham, this transformation was understandable, given the existential threat he perceived in global communism. He later expressed regret about his turn to politics as a distraction from the pure spirituality of his preaching. The gospel remained the core message of his crusades, but the specifics of that preaching received relatively little media coverage after he burst onto the national scene in 1949. Graham would receive much more secular coverage for appearances at patriotic occasions and for his friendship with politicians, usually (though not exclusively) Republican ones, beginning with his fateful courtship of Dwight Eisenhower to run for office in 1952. Graham’s remarkable access to presidents from Eisenhower to George W. Bush helped other evangelicals envision permanent proximity to powerful politicians. It was an enticing prospect.

Thomas S. Kidd is the Vardaman Distinguished Professor of History at Baylor University. This essay is drawn from his new book America’s Religious History: Faith, Politics, and the Shaping of a Nation (Zondervan).