Christians love to talk about marriage and babies, and sometimes even sex. But our earthly loves—the intimacy of bodies built on friendship and romantic affection—are so often described as little more than a physical means to a spiritual end. When we compare our earthly loves to eternity, the significance of embodied life seems little more than a temporary good, paling in comparison to the glories of a future hope.

Still more confusing, consider those puzzling words of Jesus on the hallowed institution: “At the resurrection people will neither marry nor be given in marriage; they will be like the angels in heaven” (Matt. 22:30).

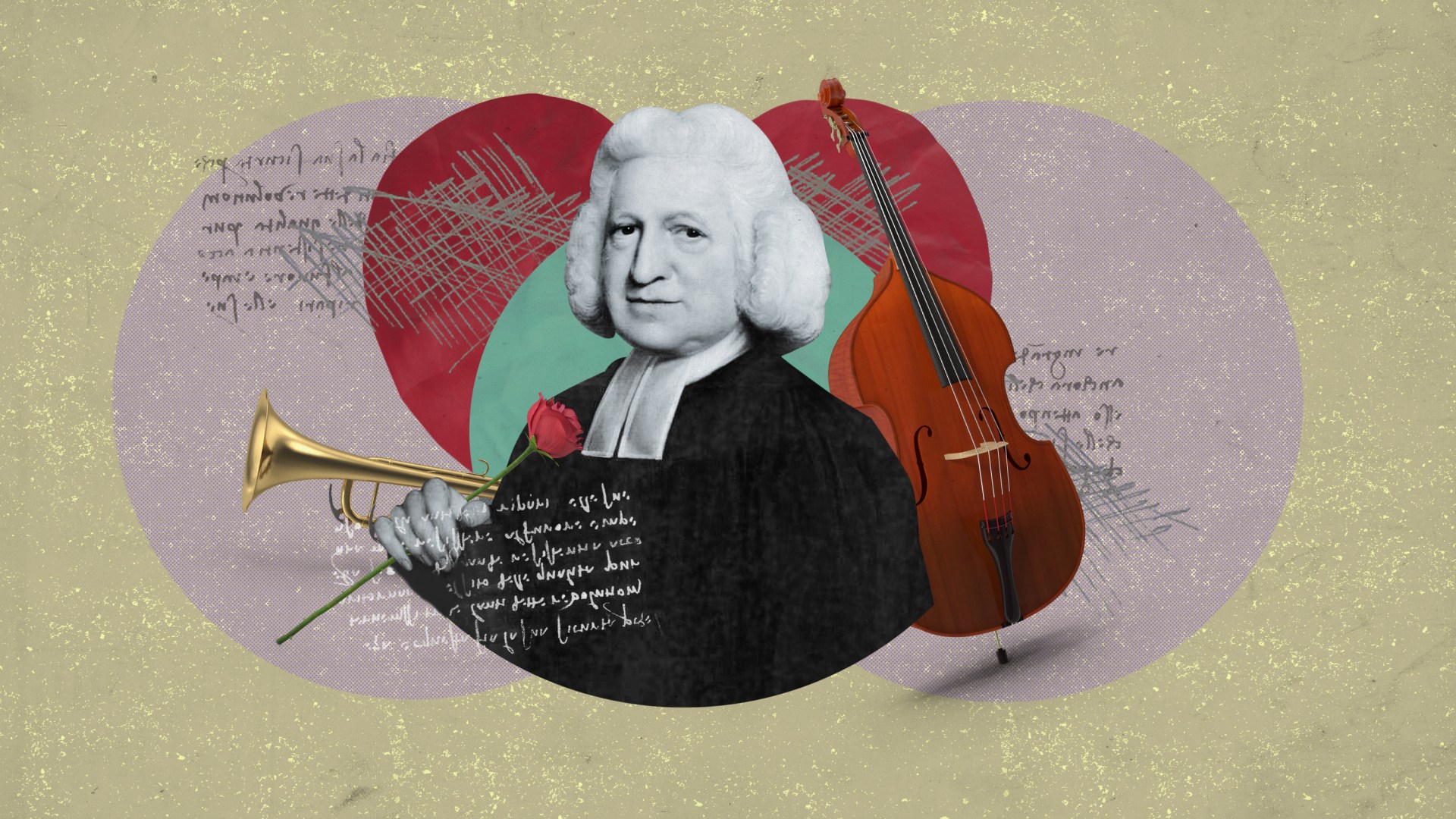

Is there any good in romantic love? The great Methodist preacher Charles Wesley—in a little-known letter to his wife—provides a fresh reminder of the power of romantic affection to shape us for good both here and in the hereafter.

The “Lesser” Wesley

Accounts of the great evangelical revival of the 18th century often neglect the life and thought of Charles Wesley (1707–1788). He wrote well over 7,000 hymns, but his older brother John has almost always been honored as the greater of the two men. Even as a child, Charles tended to be sickly, and illness plagued him for much of his life.

Yet Charles was raised in the same home as his brother John, listening to their father, Samuel Wesley Sr., preach in the Epworth church in Lincolnshire, England. Charles, likewise, learned under the tutelage of their assiduous mother, Susanna, who guided the children in their earliest years and taught them the basics of Christian belief and practice.

At Oxford, Charles was initially rather indifferent to matters of faith. After a year of study, however, he recognized the need to set new patterns. Charles began to take the religious life more seriously, celebrated the Lord’s Supper weekly, and convinced a few of his friends to accompany him in the process.

These newly acquired habits garnered the attention of fellow students, and they began to call Charles and his circle of friends “Methodists” derisively for their devotion. If the origins of Methodism can be traced back to Charles Wesley, then the inspiration for their “Holy Club” was love of God expressed in friendship with others.

Charles welcomed his brother John into the group and encouraged him to help administer it when he returned to Oxford as a fellow. Make no mistake: John’s administrative skill proved essential to the growth of what quickly blossomed into a movement, first in Britain and then around the world. In those early days at Oxford, their small group began to study classics of Western spirituality by Thomas à Kempis, Jeremy Taylor, William Law, and Henry Scougal.

When John suggested that the brothers serve as missionaries in Georgia across the Atlantic, Charles agreed, was quickly ordained, and set out with John across the ocean for Georgia. But life in Georgia proved far more challenging than either of the Wesleys expected. Charles’s health failed, while John attempted to impose a rigid discipline (and experienced a bad breakup with a young lady in Savannah to boot). Soon, the brothers sheepishly returned to London with considerable doubts about their own faith.

Converted by Love

John Wesley’s subsequent “conversion” at Aldersgate Street in London is well known, but fewer realize that Charles experienced his own “heart strangely warmed” experience only a few days before. On Pentecost Sunday (“Whitsunday”), May 21, 1738, Charles attained what might alternately be called a deepening of faith, a new birth, and an assurance of God’s love that helped launch one of the great revivals in modern Christianity.

As he lay sick in bed, Charles experienced what he described as a new “Pentecost.” He heard the voice of a woman, calling out to him: “In the name of Jesus of Nazareth, arise, and believe, and thou shalt be healed of all thy infirmities.” Charles records in his journal: “The words struck me to the heart.” In a moment, Charles, with “strange palpitation of heart,” declared “I believe, I believe!”

Three days before John Wesley’s Aldersgate experience, Charles beat John to the punch. He came to recognize the love of God in the presence of the Spirit, dispelling the darkness of doubt from his heart. The event was so moving that he later memorialized the day in one of the great hymns in Christian history, “For the Anniversary Day of One’s Conversion,” more popularly known as “O for a Thousand Tongues to Sing.”

In fact, the hymns of Charles Wesley are replete with references to love. At Easter, Christians around the world repeat the words of his most famous composition, “Christ the Lord is Risen Today,” and declare “Love’s redeeming work is done, Alleluia!” Elsewhere Charles praises “Love divine, all loves excelling” and honors God’s great and “universal love.”

Charles believed that love was at the heart of the gospel. While his brother caused controversy for teaching that “perfect” love could be known in an instantaneous blessing, Charles emphasized the gradual process whereby a Christian grows in a pilgrimage of faith.

For Charles, the new birth initiated a journey. According to his leading biographer, John Tyson, Charles Wesley looked for the complete realization of perfect love at the end of a life lived from grace to grace through suffering.

Charles and Sally

The brothers soon launched into ministry together. Methodism spread rapidly, particularly in the industrial areas of England where the Church of England seemed unable to respond to rapidly growing communities. At the urging of their friend, the fellow Methodist George Whitefield, the two took up open-air preaching and soon discovered crowds of listeners in the thousands.

Still, Charles longed for more. He was friendly by nature and personable. While some thought John too rigid, Charles always had an expressive and passionate character that complemented his brother. His friendship with Sarah “Sally” Gwynne, whom Charles had met during ministry in Wales, soon flowered with the prospect of romance.

Friendship served as the basis of their relationship: Charles and Sally remained little more than friends for a year and a half before any signs of deepening affection appear in his journals. Surviving on the income of a writer and traveling minister was a grim prospect, and Sally was 18 years his junior, so the already rigid social obligations of a proposal for marriage were made even more complicated than they might have been.

Sally’s mother insisted that Charles prove his ability to support her daughter, though establishing an income of 100 pounds a year was no small feat. Eventually, with the publication of a new hymnal, the support of his brother, and the timely intervention of another pastor, the Gwynnes agreed to the match.

Charles and Sally were married on April 8, 1749. His journal records the idyllic details of the scene: “Not a cloud was to be seen from morning to night.” They arose early, spent more than three hours in prayer and singing, and proceeded to the church.

At the threshold, the pair recalled the bitter prophecy of a jealous associate—the two would be unable to cross the door of the church that morning. Charles and Sally looked at one another and smiled. “We got farther,” he knowingly records. Sally’s father gave his blessing, and John joined their hands, “It was a most solemn season of love!”

Charles seemed to understand that such a joyous celebration of love could not be fully appreciated by a stranger. For him, the wedding was among the most powerful experiences of God’s presence—no less than the heights of grace in celebrating the Lord’s Supper. Yet when one man passed by the church, he only commented that the scene looked more reminiscent of “a funeral than a wedding.” Their friends knew better.

Abiding in Love

The letters shared between Charles and Sally, while often discreet, reveal a tender and romantic love that shaped the teachings of the Wesleys and the Methodist movement broadly. No leap of faith is required to see how the love he knew in marriage contributed to his understanding of the love of God.

From the beginning of their relationship, Charles closely identifies trust with love, as when he asked in the “loving openness” of his heart if Sally could trust her life to his care. Her answer, “with a noble simplicity,” was only “she could.” Elsewhere, signs of their abiding affection are discernable in brief references of mutual concern or in the tantalizing record of one entry: “Every evening we retired to pray together, and our Lord’s presence made it a little church.”

One little-noticed letter stands out for a remarkable statement that ties the deep affection Charles had for Sally with his own awareness of God’s grace. Dated Whitsunday, 1760, Charles’s letter begins with a recollection of the work of God’s grace so many years earlier, his “Day of Pentecost”:

My dearest Sally,—This I once called the anniversary of my conversion. Just twenty-two years ago I thought I received the first grain of faith. But what does that avail me, if I have not the Spirit now?

The letter provides a reminder that Charles still looked to the past for signs of God’s work in his life. Yet the experience of faith so many years before, while still remembered, remains only a memorial without an ongoing awareness of God’s presence in life each day. Then Charles inscribed what must surely be regarded as among the most romantic statements ever penned to a lover:

Eleven years ago He gave me another token of His love, in my beloved friend; and surely He never meant us to part on the other side of time. His design in uniting us here was, that we should continue one to all eternity.

Charles Wesley, as with his brother John, rejected a severe fatalism they perceived in Calvinist predestination, yet here he offers a sign of affection so great that he cannot imagine life, even in the resurrection, apart from Sally. His wife, partner, and friend had come to serve as a means of grace—an ordinary channel of God’s generous and loving presence in his life.

Embodied Life

Even if we didn’t know anything about their personal lives, Charles’s hymns offer clues to the ways that marriage shaped him. Strikingly, for all their love, Charles and Sally were no strangers to suffering.

In his Hymns for the Use of Families (1767), Charles’s compositions reveal how marriage and family brought intimate acquaintance with the joys and griefs of embodied life. There are numerous hymns devoted to the theme of love but also occasional verses with prayers of thanksgiving or sorrow over ordinary cares.

A series of touching compositions relate to pregnancy and the approaching pains of labor and delivery, and while some hymns celebrate the safe delivery of a child, others relate to sickness and death. In a most affecting hymn, Charles mourns the death of their second child, Martha Maria Wesley, in juxtaposing “One sad moment of fruitless woe” with the “Love, which every want supplies, / Love of one that never dies.”

Amid all these joys and griefs, Charles celebrated the love he found in Sally. Even in the sorrows that accompanied marriage and family, he found himself drawing closer and closer to the love of God. He didn’t feel the need to qualify his love for Sally as a secondary good, a shadow of the love he had experienced on that great “Day of Pentecost.” Instead, he recognized in this most romantic love something of the profound mystery that would bind them to one another even in the new creation.

In this, Charles Wesley confessed a profound truth of Christian faith—one that is too often forgotten in our desire to set aside the cares of this world: Our bodies are not meant to be discarded as refuse, sloughed off in favor of some disembodied life in the Spirit, but renewed and glorified in the perfecting love of God.

Of course, romantic love often fails to match such flights of affection as Charles and Sally Wesley discovered in one another. Unrequited love may bring profound heartache. Partners grow sick and die. Others face the cruel reality of affections misdirected to another. Sometimes the weight of suffering hinders the necessary mutuality of friendship and the willingness to press on in the journey together.

Indeed, some may choose to sacrifice romantic love entirely for a life of celibacy, choosing to direct such energy into friendships and service for the good of the community. Love is complicated, to be sure, and loneliness and shame may heighten our disillusionment with declarations of its potential for lasting joy.

Still, these examples of love’s frailty ought not diminish the potential for good in romantic affection. In attending to the love of another in this world—whether in the tender care for another person in loving acts of romantic mutuality or in nurturing a lover in times of pain, grief, and sickness—we embody the love of God.

The story of Charles Wesley reminds us that the goods of friendship and romantic affection are no passing fancies to be discarded in favor of a future disembodied life. Love is part and parcel of the promise of our total salvation. In the warm embrace of another, I come to know the love of God, on earth as it is in heaven.

Jeffrey W. Barbeau is professor of theology at Wheaton College. His latest book, The Spirit of Methodism: From the Wesleys to a Global Communion, will be published this summer with InterVarsity Press.