In this series

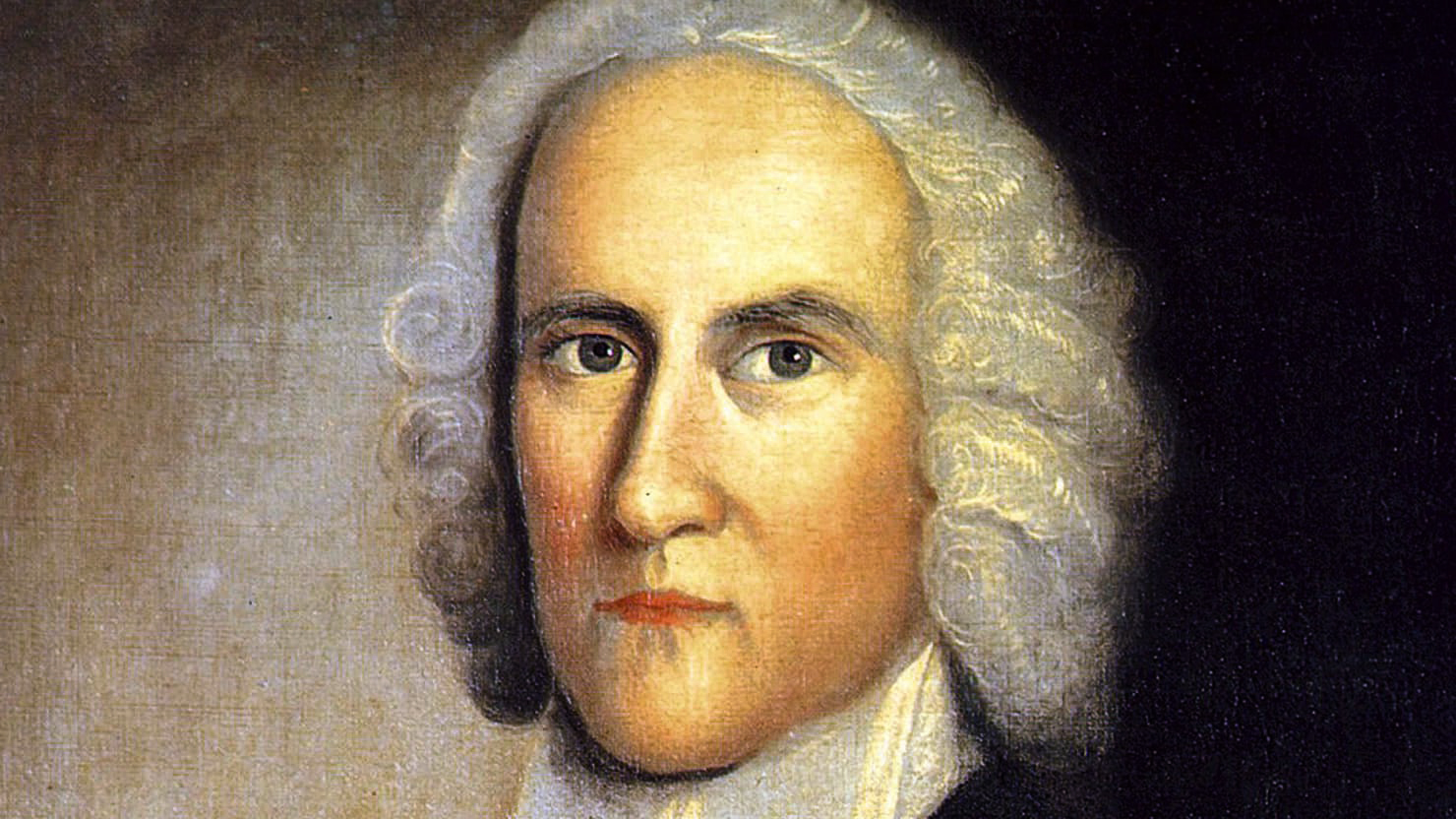

Popular caricatures of Jonathan Edwards’s theology focus almost solely on divine wrath, usually in reference to his infamously titled sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” A deeper read of his theology, however, discovers instead that God’s love is the impetus for Edwards’s understanding of salvation.

“Everything that was contrived and done for the redemption and salvation of believers, and every benefit they have by it,” Edwards avers, “is wholly and perfectly from the free, eternal, distinguishing love and infinite grace of Christ towards them.”

Christ has loved his people from eternity. All of God’s economic activity is done with redemption in mind, which means that creation is subsumed under the work of redemption (which is itself subsumed under the Father’s eternal love of the Son). It is because of the Father’s infinite love for the Son that the elect are accepted by God, having been purchased by the Son’s own love for the elect: “Because of the infinite worthiness and excellency of Christ and his dearness to the Father, the Father is willing for his sake to accept of those that have deserved infinite ill at his hands.”

In the eternal covenant of redemption, the Son covenants with the Father to give himself to his people in love. The incarnation is the embodiment of that love. Edwards boldly declares that “by the incarnation [God] is really become passionate to his own, so that he loves them with such a sort of love as we have. … Now this passionate love of Christ, by virtue of the union with the divine nature, is in a sort infinite.”

Robert Jenson responds to this proclamation by claiming that the idea “that God, as incarnate, is passionate in the very way we are passionate is the heart of what theology has rarely dared say about him; Edwards just goes ahead and does it.” It is important to notice the affective dimension in this proclamation. The incarnation was an act of passion—an act of affection—and as such, entails an overflow of God’s affectionate life within a creaturely register.

The beloved Son of the Father, who has the love of God without measure, pours forth this love to his people. Ultimately, the atoning suffering of Christ is regarded as the elect’s because of their union with him. Christ is so united with the elect, in fact, that they are “justly looked upon as the same.” As Edwards goes on to explain, “Now there is no other way of different spirits’ being thus united, but by love.”

This love is a thorough love, a love in which the lover is willing to put himself in his lover’s stead in all concerns (Christ passionately loved his people as his own). This union, of course, is the work of God’s Spirit, the overflowing and uniting love of God’s own life. It is the Spirit that unites the Son to himself and to the elect. As Edwards explains,

And if his [God’s] love to the suffering person [Jesus] be heavy enough to counterpoise his anger to the offending [sinners], yet it will not counterpoise it unless it be laid in the balance with it to counterpoise it, unless it be put in the opposite scale; which it is not, unless the suffering person suffers for the sake of the offending and out of mere love to him, or unless his love be great enough to put him in the place of the offender.

It is not enough that Christ suffers and dies; he must suffer and die out of a dual love: love to his Father and love to the offender.

Now the foundation of the propriety of this imputation of righteousness seems to lie in these two things: in Christ’s union with God, and his union with men. It would not be proper that the righteousness of any person should be accepted by God for another, but a person that was one with God; nor would it [be] proper that it should be accepted for any person, but only a person that he is one with.

In other words, Christ must embody for humanity the love of God and love of neighbor. Edwards gives a precise analysis of this dual love in an attempt to justify how a holy God could allow himself to accept sinners into his own life. He spent the most significant space musing about these issues later in his life, and, at face value, took a new direction (or, if nothing else, utilized new imagery not used previously).

But while the imagery is new, closer examination reveals that these musings follow the same trajectory he had traced from the beginning, namely, that “everything that was contrived and done for the redemption and salvation of believers, and every benefit they have by it, is wholly and perfectly from the free, eternal, distinguishing love and infinite grace of Christ towards them.” God has moved toward his people in love, and this is the underlying reality of Edwards’s understanding of the atonement.

Relations of Love as the Foundation of the Atonement

To advance his account, Edwards turns to the imagery of a patron, a friend of the patron, and a client: Jesus, God the Father, and the believer, respectively. To articulate this model, Edwards utilizes the category of merit.

The key question in this scheme concerns how the patron (Jesus) covers the lack of merit in his client (believers), while still maintaining his relationship with his friend (Father). For this relationship to work, the patron must have an abundance of merit, enough to cover the client’s lack. Edwards explains, “’Tis not unreasonable, or against nature, or without foundation in the reason and nature of things, that respect should be shown to one on account of his relation to or union and connection with another.” The believer’s relation with Christ and union with Christ are one in the love of the Spirit.

The focus, here, concerns how union can ground respect. To keep in mind the difficulty, we need to know that, for Edwards, sin against God is an infinite transgression. The believer has lost all that makes her or him moral, holy, or good. How can Christ maintain his relationship with his Father if he receives these people into life with himself? To use imagery closer to Edwards’s own idiom, how can the Father and Son maintain their intimate union in the event that the Son takes a prostitute as his wife? How can she be accepted into the Father-Son relationship?

In order to explain the logic of redemption, Edwards makes several assertions. First, he points out that just any old union will not do. Jesus’ ability to vouch for his client—while still being accepted by the Father—depends upon the greatness of the union between Jesus and his elect people. How strong must this union be between Christ and the elect in order for the Father to accept them?

Edwards claims that Jesus’ “heart is so united to the client that, when the client is destroyed, he from love is willing to take his destruction on himself.” Jesus’ love is the main feature of this image, not only because Jesus loves his creatures enough to take their destruction upon himself, but also because the union between them is Christ’s love to them. Because of the strength of this union of love, the believer’s interest is Jesus’ own. The believer’s plight is now Jesus’ plight because he has given himself so fully to the believer.

Second, and building on the first assertion, Edwards turns to the nature of Christ’s atoning work specifically, noting that the atonement does not simply involve paying off a debt out of his abundance (which is true); it also entails Jesus’ personal suffering for the interest of the believer.

Edwards’s concerns can be easily detected. The apparent dilemma is this: The patron must remain friendly with his friend, but taking on a client that reeks of sin and vice may shatter the patron-friend relationship. This concern is especially important in a soteriology of participation. There are two things that need to be intact when a patron is united to an offending and unworthy client, namely, his regard for his friend (in this case, God the Father) and his regard for virtue or holiness (“For in these two things consists his merit in the eyes of his friend”).

Edwards turns his attention, for the moment, away from God’s people and focuses on Jesus’ identity in relation to the Father. Christ’s perfect relationship with his Father is the ground and, for Edwards, the reality of salvation. But it is not only Christ’s standing before the Father but also his standing before the blindfolded justice of virtue that is necessary for the salvation of sinful creatures. Christ must be infinitely worthy in his own life in order to secure salvation for the elect.

To accept someone unsavory, the patron must be truly great, and the friend of the patron must have the deepest regard for him. If the Father has a great degree of regard for Jesus’ dignity, then “there is a sufficiency to countervail all the favor that the client needs.” In this circumstance, the lover must be willing to part with his own welfare for the sake of the beloved. Jesus must regard the believer’s welfare as his own and must love the believer to such a degree that it is a part of his self-love.

As with all persons, Jesus’ love internalizes the believer into his own self-love. Jesus’ love to himself, and, in this sense, the Father’s love to him, must now include the believer. “Christ loves the elect with so great and strong a love, they are so near to him, that God looks upon them as it were as parts of him.”

Now if it be inquired how much love is sufficient for that, I answer, that if Christ loves men so that when they are to be destroyed, he out of mere love is willing to take their destruction upon himself—or what is equivalent to their destruction—then is Christ’s love sufficient in God’s account to make them one, for this reason, because when it is so, his love is such as does as it were of itself put the love in the beloved’s stead, even to the utmost and the most extreme case. That love that makes the lover willing to be in the stead of the beloved, even in the last extremity and where the beloved’s utmost is concerned, even to perfect ruin and destruction, such love makes a thorough union.

For Edwards’s redemptive reasoning to work, the patron and client must be united together in an act of faith and love. But the patron and the friend—Jesus and the Father, respectively—must be united to provide the foundation for Jesus to act on behalf of his people. Jesus can save his people, not only because he shares the nature and love of the Father, but also because he shares the nature of the saints and has loved them into union with himself (recalling that this union is in the Spirit of love).

If it be inquired how great a love it ought to be, in order to their being accepted for his sake, I answer: the love should be so great as to be justly looked upon [as] a thorough union with them, so great that Christ may be justly looked upon as making himself one with them, such a love as is thoroughly assuming them into union with himself.

Furthermore, because Jesus has taken on the sinners’ cause as his own, suffering all that was needed for their full redemption, they can know true salvation in him. The role of the clients, simply enough, is to be clients—to cleave to Christ and trust that he, their patron, will do all that is needed in recommending them to the Father.

It is here that Edwards’s patron-client imagery gives way to his prior and more fundamental metaphor for the relation of the elect to Christ—that of bride and groom. The uniting of faith is the uniting of marriage, not only between the church and Christ but also between the individual soul and Christ.

In this union, the bridegroom has made his bride’s interest his own. In this marriage, not only has her incredible debt been cast away, but she has also received Christ’s merit as her own (i.e., double imputation). In this, she is ushered into the household of God and shares Christ’s standing before the Father.

What grounds this atoning work, from beginning to end, is love. Put another way, the logic of the atonement is discovered in love-in-relation; the atonement works because of the love that the Father and Son share, as well as the love that Christ has for his people. This point does not yet explain the mechanism of the atonement; nevertheless, whatever else Edwards says about the atonement should be interpreted through the lens of this particular insight.

Oliver D. Crisp is professor of systematic theology at Fuller Theological Seminary. Kyle C. Strobel is associate professor of spiritual theology at Talbot School of Theology, Biola University.

Adapted from Jonathan Edwards: An Introduction to His Thought; Copyright © 2018 by Oliver D. Crisp and Kyle C. Strobel. Excerpted by permission of William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. All rights reserved.