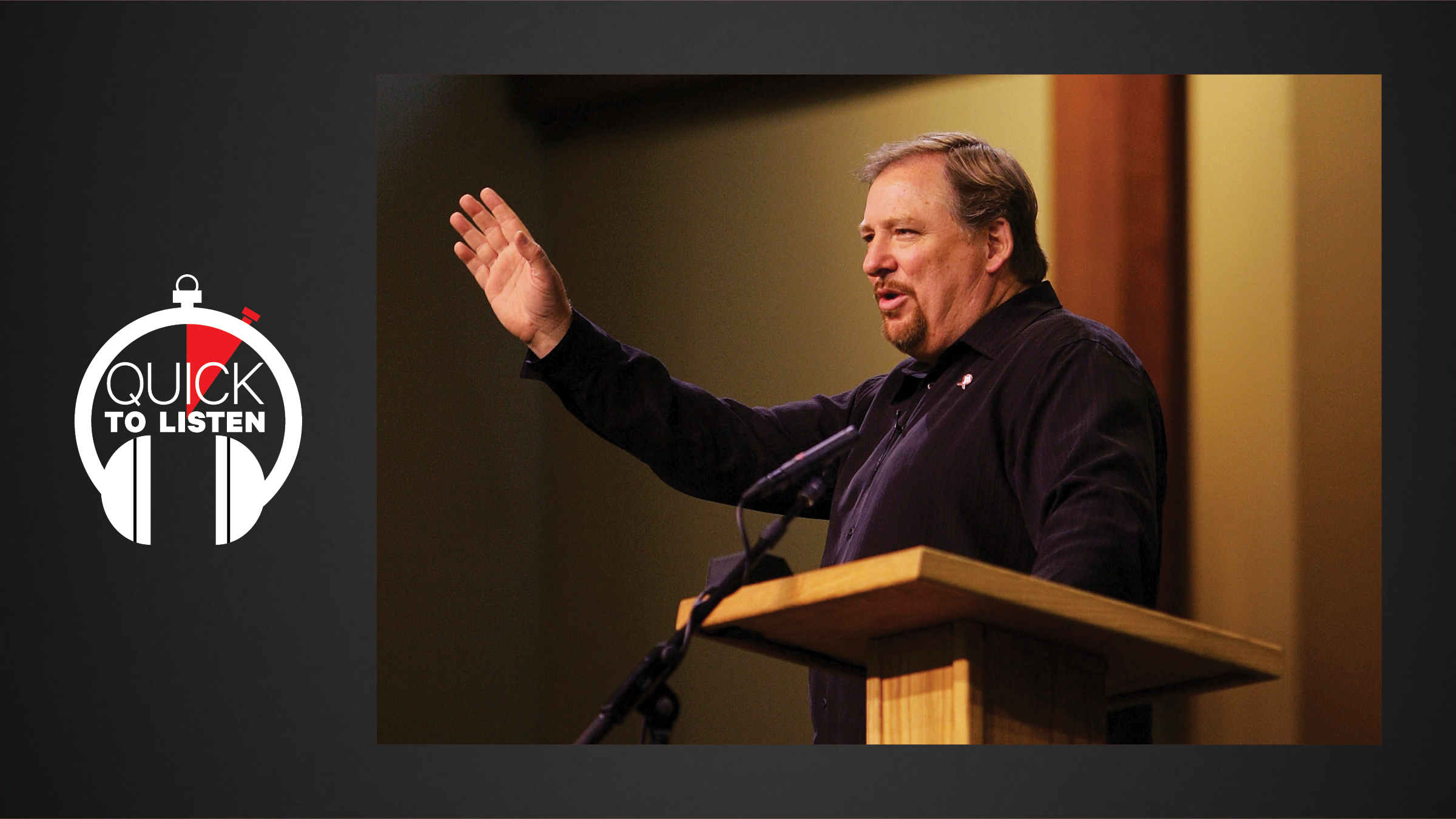

After more than 40 years leading Saddleback Church, Rick Warren has announced his retirement.

“This is not the end of my ministry,” Warren told his congregants on Sunday. “It’s not even the beginning of the end. … We’re going to take one step at a time in the timing of God. … God has already blessed me more than I could ever possibly imagine. I don’t deserve any of it, and so this next transition in my life is something I am anticipating with zero regrets, zero fears, zero worries.”

The Southern California-based megachurch has begun looking for Warren’s successor.

Warren’s ministry has had national and international significance. He is the author of the best-selling The Purpose Driven Life. He championed evangelicals fighting AIDS overseas. After his son died of suicide in 2013, he and his wife Kay began a mental health ministry.

Overall, Warren’s ministry has not been as polemical as many of his fellow Southern Baptist church leaders. But he faced controversy after praying at Obama’s 2008 inauguration after he campaigned against same sex marriage that same election cycle. Several months ago, he apologized for Saddleback’s children’s Sunday school curriculum video which used Asian culture stereotypes to teach kids about the Bible. Last month, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary president Al Mohler criticized Saddleback after it ordained three women as pastors.

Gerardo Martí is professor of sociology at Davidson College and the author of numerous well regarded books, including The Deconstructed Church, American Blindspot, and The Glass Church.

Martí joined global media manager Morgan Lee and news editor Daniel Silliman to discuss Southern California evangelicalism, how Warren reached the suburbs by looking at amusement parks, and what informed his political strategy during Trump’s presidency.

What is Quick to Listen? Read more

Rate Quick to Listen on Apple Podcasts

Follow the podcast on Twitter

Follow our hosts on Twitter: Morgan Lee and Daniel Silliman

Follow our guest on Twitter: Gerardo Martí

Music by Sweeps

Quick to Listen is produced by Morgan Lee and Matt Linder

The transcript is edited by Bunmi Ishola

Highlights from Quick to Listen: Episode #268

In comparison to the rest of the country, how would you describe evangelicalism in Southern California?

Gerardo Martí: Well, something that a lot of people don't know is how religiously hot Southern California has always been.

It was founded in a place that was dominated by farms, citrus groves, and strawberry fields, and it is in this place that there came to be a stream of people from the south and the Midwest—people who already knew church, understood what church was like, and were seeking churches.

So immediately with the flow of Southerners and Midwesterners, churches began an aggressive attempt to plant their churches immediately. And they took over every available space. So before there were buildings, they took over farms and fields and barns and funeral homes and whatever school buildings were available.

And what was interesting is that it was such an aggressive place of church competition that it forced churches to innovate about how to distinguish themselves and how to attract a faithful population and continue to grow their flocks, and then eventually to be able to expand.

And out of that base is where you get some of the most interesting developments in American religion. You get Robert Schuller, Garden Grove Crystal Cathedral, and The Hour of Power broadcast; you get Calvary Chapel with their charismatic Christianity; you get The Vineyard; you get Campus Crusade for Christ expanding to all of these campuses; you also get some specific ethnic-oriented congregations—Chinese and different forms of Latino communities.

So essentially, by the time Rick Warren shows up, he has already been schooled in what has been happening in Southern California. Specifically through his mentor, Robert Schuller, and the school of leadership there, learned church growth techniques. And so using the funding and the base offered by Southern Baptist, he moved southward into an expanding Southern Orange County—which residents were moving to in order to find cheaper housing but also larger housing, while still having an American dream of that fenced-in lawn, two-car garage, with lots of grocery stores, shopping malls, multiplex theaters within easy driving distance.

The new schools promised better education, new streets promised better traffic, and new churches promised better religion.

With so many people planning churches and innovating in church space, what set Warren apart early on? How did he go from one of many pastors to this standout figure?

Gerardo Martí: Well, if you've ever encountered Rick Warren, he is a person of immense personal warmth. And so I want to give at least a little credit to the fact that he is a person who knows how to connect with people, how to communicate clearly, and how to create a shared sense of ownership. But at the same time, from the beginning, he always had a sense of what it meant to be an effective church.

He started Saddleback Community Church by going door to door, just like his mentor Robert Schuller did, asking local residents what they liked and what they hated about churches. And based on his personal survey, he came up with a marketing profile: Who is it that we're trying to reach?

Famously, that person was called “Saddleback Sam,” and Saddleback Sam had particular characteristics from the kind of job they had, the kind of family life, the kind of attitudes and orientations that they had. And basically, you can picture a collared khaki-wearing, upwardly mobile, business entrepreneur type of person who's trying to move up the ladder. And that essentially becomes the unchurched person that's being reached, who is tremendously busy but still resonates with the notion of church.

And to do that, Rick Warren didn't assume that people were already committed to any kind of a church. And so the whole goal was to make everything very easy. An easy access church. Usually, this is called “seeker-sensitive,” but the idea is to make things as easy as possible, remove any obstacles that might keep people from committing to a church.

And in doing so, they also drew on the paradigms that are available from other Southern California entertainment institutions, specifically amusement parks. So a host of subsidiary tourist attractions knew how to draw a draw thousands of people daily, manage the crowds, make things very digestible and easy. And Disneyland, of course, is king of all these.

And so Saddleback was a part of meeting that standard for capturing attention, having crowd control, keeping attractions continually fresh, and offering a saturated spiritual experience that would include the whole family.

What's an example of something they would borrow from Disneyland? What are they doing that’s borrowing from these local entertainment options?

Gerardo Martí: One of the things that's very interesting about the notion of crowd control is when you go to a church that you've never been to before, the first thing you want to know is where's the building, and where do I park?

And through a system of establishing lines, having ushers who are clearly uniformed and demarcated people, they would be able to almost immediately get you to a prime parking position and then be able to clearly show you how to get to the front door where then you would be continually ushered. So that the trip from not knowing where things are to getting into a seat was accomplished within a few minutes.

And that kind of rationalizing, of formalizing, of being able to get a flow of people to integrate into a church service was highly innovative at the time. And the fact that you had very specific people—the parking people, the ushers, the people to greet guests, the people who then take you down to the seat—all of that is seamless and you just ride the wave almost like moving along a little conveyor belt that gets you right into that place.

If you ever had a chance to visit their children's ministry, you would see a huge aquarium set up. You'd be able to see how colorful and bright it is. You'd be able to see the different options that they have for people to be able to do things. Also Saddleback allowed for things like patios, lattes, and coffee, the ability to just sit anywhere.

And eventually, they were able to create multiple church service experiences on the same campus. So you could come to one church, but if you preferred a particular kind of worship style, you would go over to this place. If you preferred a particular way of doing things that accommodated another set of sensitivities, you'd go over here. So they were able to create a surprising diversity of experiences of church on the same site.

In addition, the architecture, the color, and the scheming of things, everything was meant to feel contemporary, fresh, interesting, and very much reflective of the aspirations of what people wanted to do with their lifestyle.

So it sounds like there was the belief that we can’t assume people are going to know the “script” of church, is that correct?

Gerardo Martí: Absolutely, because the whole point is actually not to use a church script at all. The idea is to take the kinds of experiences that people already have in urban society—the grocery stores, the amusement parks, shopping malls, theater experiences—to remove all semblance of being a church and to just be this place that you gather.

So there's no dress requirement. Rick Warren himself was famous for wearing Hawaiian shirts and that happened very early in his ministry. The idea was, you don’t need to dress up in a particular way, we’re not going to use any formal language here, you don't need to bring a Bible with you. We're going to provide everything you need to know upfront or on the bulletins or the screens. And if you don't know the music, that's okay. We're going to make it really easy for you to follow along. We're not going to pressure you to sing. It's going to be loud enough that even if you try, nobody's going to hear you.

So there were a lot of ways that this was done so that it was just the easiest thing in the world to come and basically hear a speaker give a message, and not a pastor give a sermon.

There was a time when you couldn't read anything about Rick Warren that didn't mention his Hawaiian shirts. It was a very prominent feature of his. What was he communicating with that fashion choice?

Gerardo Martí: Rick Warren was right in the middle of what was often called “The Worship Wars.” And so there were churches that really felt that to do things right, you had to be traditional. You had to show respect for God, you needed to be able to have the proper, pious stance as you come in. And it's reflected in how you dress. It's reflected in what you do and how you follow directions. And it's certainly reflected in what the pastor communicates from upfront.

And so the idea of wearing the suit, to dress nicely, is the idea of being able to be your best for God. And this is something that's just incredibly pervasive. And, in fact, is one very interesting way that he countered his mentor, Robert Schuller, because Robert Schuller did not countenance casual hippy-like people coming into the services, and ushers were meant to keep people out. And it was not unusual in churches in Southern California, that if, for example, you had a baseball hat and tried to come into the service, you were asked to remove the hat or leave.

Now at Rick Warren's church, those sentiments were totally obliterated. So what he was trying to communicate is, “I'm one of you. I care. I know the circumstances of your life. I want to relate to what you're kind of dealing with on a day-to-day level. We're not going to pretend that our spiritual lives are only about a sacred moment in a sacred spot for this sacred time. Instead, what is it that we need to talk through to help you realize what it means to be in relationship with God and to live a life that has a connection to what God wants from all of us?”

And so the Hawaiian shirts were the most prominent aspect, but I think that there were a lot of other things that were readily communicated—in the architecture of the place, in the style of music that they used, in the way that they would talk. I think it was a whole package that fit into what was often called a Southern California thing, but actually was being found all across the nation as this move from traditional to contemporary was the aggressive move of trying to make religion relevant, to make Christianity relevant in a new and fresh way.

Do you find or think that there is a tension in the clearly calculated and highly detailed marketing strategy and business practices and the emphasis on authenticity, vulnerability, and accessibility that Rick Warren and Saddleback are known for?

Gerardo Martí: In my mind, these things are deeply intertwined in the revivalist tradition. And so I go all the way back to Charles Finney and how he's strived in his ministry to connect with people on a deeply personal and emotional basis, and at the same time, everything that he did was calculated, formulaic, intended to move towards a particular outcome, which he was able to do over and over again.

And we see that Rick Warren adopts a generally revivalistic and primitivist evangelical orientation. And that is that faith is meant to speak specifically to you, you are to respond specifically to it, and that every issue, every problem, everything in the world can be solved as long as you give over your life to God.

But the same revivalistic tradition believes that you need to organize the church in particular ways. And so at the same time that Rick Warren was trying to reach particular people—remember that Saddleback Sam—he also cultivated an entire ministry philosophy which became church seminars and eventually became his first book, The Purpose Driven Church.

And that first thing was arranging the involvement of people into a sort of baseball diamond, where people came and they were intended to go to first base. And the church knew how to get people to first base, and then from first base, you went to second, second to third, third to home. And the notion of the entire structure of the congregation was how to involve people into deeper and deeper levels of investment. And it also was meant to correspond to an investment in their own spiritual lives.

So that organizational dynamic with that intimacy of personal conversion and change is always implicit to Rick Warren's, but it is also in my mind, implicit to all seeker-church orientations. And it goes back to the revivalist tradition.

Plenty of pastors write books every year, but The Purpose Driven Life had a whole ministry package that developed around it. What made this book so remarkable, and why did it sell so well?

Gerardo Martí: First of all, most people don't recall that before The Purpose Driven Life was written, he had already written a bestselling book, The Purpose Driven Church and it had already reached millions of people. And I had visited pastors’ offices that had not only their copy but multiple copies so that they could give it away to other people.

The Purpose Driven Church was seen as the state of the art way of doing church for a whole lot of people. And that sense of intentionality about what to do with your ministry conveyed to people a genius about Rick Warren as a pastor. Because how do you solve the issue of church growth? How do you create greater stability for this thing called church? Everybody was worried about what was going to happen in the future, and he seemed to have figured it out.

So once he was able to take some of the principles that were embedded within The Purpose Driven Church and to convey it in a pastoral language—conversational, direct, personal, Nx with a whole lot of charm—that's how The Purpose Driven Life was born. It personalized a lot of the principles that Rick Warren had been working with, and it immediately fell into the hands of people who already were sold on him as a person who had figured out how to move the church into the future.

So what Rick Warren was able to do was to give these pastors, already convinced of the methodology, a new tool for reaching people. And The Purpose Driven Life isn't as much about the individual who picks it up off the shelf, it's more about the ministries who take this book and say, “Let's use this, let's have a small group, or here let's work through this together.” And this Purpose Driven Life book was a lot less intimidating than giving people a Bible.

So, to me, it was a way of giving these churches a new tool for making their revivalistic Christianity relevant to a new population. And it did it in such a nicely packaged way that it really took off.

What are some of the critiques that began to emerge about this particular model and what type of people love the model?

Gerardo Martí: In evangelicalism, many people don't have to go to seminary to be in ministry. You're just kind of following whatever you seem to know. You can be ordained in ministry because you care about the church, and you've served as a volunteer and been dedicated. So you're really following the model of someone else.

And so you start to go, how do I figure out budgeting issues? How do I attract people and keep them? What do I do with their kids? If you staff for growth, how do you actually work that? So all of those complications were initially solved by The Purpose Driven Church and the network of people who thought more logistically about churches. The logistic orientation became important. And that is different from how to preach homiletics. It's certainly different from how to do pastoral counseling. So for a lot of people, because of the apparent success that it had, this seemed like a breath of fresh air.

What Warren was constantly criticized about was not having depth, that depth was missing. Sunday morning was not necessarily in-depth Bible study and what he was asking people to do wasn't to go out on the mission field or things like that. And even communion, which for many churches is something that must be done every Sunday, they were distributing in small groups with no ordained pastor at all. His model didn't seem to have a lot of the demands of discipleship. So that's the critique that Rick Warren often fell into.

There was also the belief that the music that they were using lacked any theological substance—no hymns anywhere. And there were no formal membership requirements. So it's like, where are people learning things? What does it mean to actually grow in the faith? That remained very ambiguous for a lot of people.

And I think then, a lot of others would say, “We’re doing it better,” and they would compete with Rick Warren and his style of church. So you had people leaving churches going to Rick Warren’s, and then you had some people who felt that they had outgrown Rick Warren's church and would siphon into far more fundamentalist congregations.

Was there ever any critique about the individualistic focus that much of the Purpose Driven rhetoric seems to reinforce versus asking American Christians in particular to transcend their individualism?

Gerardo Martí: No, because evangelicals don't think this way. Evangelicals think that the center of change happens among individuals and that's what's important. That's been that way for a very long time. It's just not a conversation and it's still not. So this critique doesn't exist.

And what they would say, “of course it's social, people are in small groups,” “of course, it’s social, they're involved in ministry,” “of course, it's social. We gather as a congregation.” So in their minds, they don't think of it as individualistic because they see people in interaction.

But the framework that they're missing is really to understand how history and social structures affect the lives of people. And so I don't think they even understand things like how Southern California developed to begin with, or what is the religious history that's embedded in the people that come to church, or what is affecting the work and family lives that create all of the tensions and the conflicts and the difficulties that they're trying to therapeutically preach their way out of. Those are things that just aren't even in the conversation.

The message has tremendous resonance with so many people that they don't see a need to change.

Warren is also known for his engagement with social issues. Can you talk about his involvement in politics and things like calling evangelicals’ attention to AIDS?

Gerardo Martí: You find that evangelicals like Rick Warren do believe that they have relevance for the world as a whole, and so they're paying attention. And what I want to emphasize upfront is that he still believes that conversion and commitment to God are primary, and has always felt that that was first and foremost of anything that he did.

In terms of the 2008 election, Rick Warren became aware that he had a very public voice and a very large following of people who were paying attention to him. And so he very quickly saw himself as more than the pastor of a local church, and he started to think that perhaps he could be a part of helping evangelicals come to a different sensibility about things. I think it was a moment of, “I've got power. How do I want to use this power responsibly?”

And so the attempt to play out a non-partisan approach to politics and try to not put forward a particular agenda led to him inviting Barack Obama and John McCain to the church for a public conversation. And that kind of thing was very notable at the time because it signaled what I think every pastor wants to say: my congregation matters, we talk about important things here, and we bring guests that matter. Certainly, his mentor, Robert Schuller, had done that for a very long time, and others would do it as much as possible.

But at the same time, what he didn't talk about was politics. So it was more about connecting to forms of power than it was about looking at policies and attempting to understand structural changes. I don't think that Rick Warren ever became sophisticated about policies, but I do think that Rick Warren knows something about power. And so the attempt to play at a non-partisan political awareness is how that worked.

But overall, I think all of that hit him much harder than he anticipated. Because every time he stepped into something that was a political arena, he always discovered that the people that were supposedly a part of his constituency held highly partisan and very specific views and were far more combative and felt that the world was a moral battleground that had to be won. And so Rick Warren didn't approach things in that way, but the people that he was closest to, and in his denomination, the Southern Baptist, certainly did. And that's the back and forth tussle that he constantly had.

Even his introduction to the AIDS epidemic was not through domestic politics or policy. It was through his exposure to what was happening in Africa. So you have as a person who goes to a part of the world that's not the United States, and all of a sudden discovers there are actually large structural issues that need to be dealt with. He had no vocabulary for how to deal with structural issues once he discovered them.

And so then he starts to go, “Okay, let's do something about AIDS in this foreign country.” But at the moment at which you started to talk about what you need to do to address AIDS—which has to do with sex education, distribution of condoms, and other things like that—he ran smack dab into the machinery of family-values politics n the United States.

And so that created this need to assert for himself, “I cure about the conversion of people. I care about people changing and giving their lives to God first and foremost.” And then, along the way, try to address these things with all kinds of different compromises and always with these conservative-culture warrior people nipping at his heels that he wasn't doing it right.

And so Warren's brand of person-centered politics always had a problem. It always ran into its limitations.

Let's pivot and talk about Warren's personal life, specifically his son's death by suicide. How did that affect Warren personally and also his ministry at large?

Gerardo Martí: When I found out about Rick and Kay Warren's son’s suicide, I think I responded like many. Just a real sense of grief and sadness. Because you don't get the impression that these are people who don't care about their kids, right? This is someone who's been invested. And for anything like that to happen to anyone, I would hope we would all have deep compassion. And I think if anything, I was surprised at the time amount of grace, the willingness to talk about it publicly, and the amount of detail that was shared right away.

I think that Rick Warren accepted that he was a public person and that if he was going to deal with this kind of trauma, he needed to do it in a way that would allow people to see this is how you work through things. It's not a perfect way of dealing with things, but it is the way that we do it, that’s sensitive to the lives that we've given ourselves to.

And I think that what that did was take him into understanding yet another social problem, one that deals with issues of mental health. The bridge was set. It wasn't that he came to be aware of mental health issues in some broad and abstract way. He was affected by the death of his son. And for evangelicals, the personal connection to a vast social issue like that is what allows for a bridge to then talking about a larger social issue.

And so for many people, it allowed greater conversation about these things. It allowed further permission-giving to seek professional help and not just relying on prayer. To actually see that certain things are so significant and that can be so troublesome and that there can be things that you don't know, that can happen unexpectedly, and you can't just wish them away by being a good spiritual person.

So I think that as he walked through that, he allowed for new sensibilities that became very important for a whole lot of people. And I think that is significant, and he and his wife deserve a lot of credit for that.

You’ve mentioned that he seemed to feel this responsibility in part because of his celebrity or his sort of public renown. At what point does Warren become a celebrity, and what kind of Christian celebrity is he?

Gerardo Martí: In my mind, by the mid-nineties, the name Rick Warren was already abuzz. And if Rick Warren were to come and show up somewhere there was a high level of anticipation that something good was going to happen. He was always seen as someone who stood out in his charismatic persona, that he had somehow been able to do what most people still don't quite understand how to do: how do you start a church from scratch and be able to make it financially viable and stable?

So Rick Warren's celebrity went in waves. There was the inner circle of people in the Southern Baptist and among a certain scope of mostly white evangelicals. Then people finding out about his church started to say, “How do I do this?” and the requests for figuring out how to do church become so burdensome that that's why he organizes conferences. That’s how Robert Schuller did it. That's how Bill Hybels did it. That's how Erwin McManus did it at Mosaic in Los Angeles, that's how's Hillsong does it.

You have all these places that once it feels like they've unlocked something, they've gone to a different level very quickly. Church circles start to knock on doors, call, email, visit, sometimes showing up in vans to just soak in what's going on and then talk the ear off any volunteer who's willing to talk. So the conferences are a way of channeling all of the curiosity and packaging the formula. It is the incessant demand from church leaders for how to do church that creates these conferences.

So once Rick Warren started to package his formula for success, that's what became The Purpose Driven Church. And The Purpose Driven Church expanded him out because church leaders who are not evangelical are also very attentive to things. They feel like they need to be attuned to what's happening in ecclesial circles. And so what makes him much bigger. S

So when The Purpose Driven Life became a bestseller, that's when I think he became more of a pop culture phenomenon. He became someone that was known in popular culture. And I think his most famous moment was when a woman was being held hostage and she talked the man through The Purpose Driven Life and led him to convert, and he ended up letting her go. That was the peak moment of Rick Warren in popular culture until the Obama-McCain thing, and when he became the one person to pray at Obama's inauguration.

It’s interesting how far beyond the Southern Baptist his influence goes. What was his relationship with the SBC, and how does he relate to the SBC over the years?

Gerardo Marti: The Southern Baptist likes to say that individual churches are free to do what they want and that they have a lot of discretion on their own. So there's always a difference between the pronouncements of the SBC as a denomination and what happens in the different churches.

So out of the thousands and thousands of churches and pastors, you have plenty who deliberately obscure their Southern Baptist connections because they don't want to be associated with the pronouncements being made by the SBC. And Saddleback is certainly one of those churches. These churches don't want to be burdened with having to answer for a body that they weren't a part of making those decisions but take the benefit of the things that they do resonate with and the things that are good for them by remaining within the SBC.

But the other thing is that the SBC often gives a lot of hands-off autonomy to churches if they are successful. It’s almost like they don't want to question God's work if God is indeed doing something good. And these churches make a point of showing how they do that. Probably the most important figure in a Southern Baptist church is how many baptisms you accomplish in a year. That's more important even than the number of attendees. And Rick Warren would often say how many people have been baptized through his ministry, and they have baptized over 50,000 people through their ministry.

I don't think that there's any other Southern Baptist church that would come close to that. That's a spectacular number. And so no Southern Baptist is going to argue with what they see as the sine qua non of ministry effectiveness.

One of the most recent things to happen at Saddleback is the ordination of three women as pastors. What is the significance of Saddleback doing that, especially in light of Warren's retirement being just a couple of weeks away?

Gerardo Martí: First, I think that it should be clear that there are different levels of what it means to be ordained in a church. Many churches make a difference between being licensed versus being ordained. Licensure meaning that that you can be employed by the church, and it gives you certain tax benefits, but it's meant to be renewed on an annual basis. While being ordained is being set apart for ministry. It can also have tax benefits but is not something that has the same requirements to re-up as often.

And to my knowledge, I believe that many women in Southern Baptist churches have received ordination, but are not called pastors. These are your children's ministry people, sometimes some worship or music directors, but there are a variety of people who've worked in Southern Baptist churches who have essentially been ordained without being called pastor. So what would be different is for them to be publicly acknowledged with the same role and title of being a pastor. That, I think, might be distinctive.

But I know of husband-and-wife teams in the Southern Baptist that because the wife is under the headship of her husband, then it is okay for her to be called pastor. So I think that that might be a little bit more heat than light in what's going on there. That's my opinion.

The presence of Donald Trump and his overwhelming support from white evangelicals was a huge story over the past four years. What was the approach that Warren took to Trump? And to what extent did it change over Trump's campaign, and then eventually Trump’s presidency?

Gerardo Martí: Well, we're going to continue to unpack the white evangelical support for Trump for probably the rest of our lives. I think when it comes to Rick Warren specifically, I think he took away a lot of lessons out of his involvement in the 2008 campaign and his association with Barack Obama. The backlash that he received was so strong, so persistent, so forceful that I think it burned him from being involved in national-level politics at all. And he decided to be ambivalent, at best, about Donald Trump.

So the continuity was that Rick Warren still did not engage in issues of policy, did not understand some of the larger dynamics involved, and treated things as more of like this non-partisan politics that we're kind of involved in. He sort of affirmed some things but didn't really speak out against anything.

I think that we know that Rick Warren holds certain moral positions that would be consistent with a conservative white evangelical position—the same ones that have been that have supported Donald Trump and have translated into certain kinds of policies, particularly affecting women, gender, and sexuality issues.

But overall I think that he immediately saw that if he had already dealt with so many issues with Obama, who in his mind seemed to be faith-friendly, and he wasn't going to touch the issues with Trump. So he kept his distance from it. And I think that that remained consistent throughout Trump's presidency.

Did his relative silence cost the church in any way or at all? Did it undermine the goals of his ministry? Or was he able to successfully sit this one out in a place when a lot of other high-profile pastors were not?

Gerardo Martí: My read of Southern California, particularly that area of South Orange County, is that it’s more conservative than progressive. It's whiter than other parts of Orange County. And it remains connected to the evangelicalism that was the suburban white evangelicalism that started the religiosity of Southern California as a whole.

So there is a comfortable conservative ethos—a pro-capitalist, pro-family, anti-gay, homeownership, work hard, get an education—that I think he can comfortably work within. And so there's no need to confront that. It is the lay of the land. And he can seemingly be nonpolitical and have things just continue to go that way.

So there are some people who, of course, would like to have a much more forceful demand to address certain things. But there's just not going to be the same push to try to figure out things related to immigration, for example. I think most people just think that talking about white supremacy is kind of odd. It's just not something that is discussed. It's the environment or the culture they swim in. And so there's no need to challenge that.

There's been a few times that Warren has ended up apologizing for his or the church’s insensitivity on race issues, particularly towards Asian-Americans. How did Warren generally approach the issue of racial reconciliation or racial justice?

Gerardo Martí: I think that if you know anything about Promise Keepers and the general orientation that they took to racial issues, that's exactly where Saddleback would be. And so Saddleback embraced all the things that seemed good, but they still approached it on an interpersonal level.

And so you would see a very welcome and open attempt to try to diversify the staff or to try to incorporate some racial representation perhaps liturgically or publicly, but you're not going to find a Black Lives Matter sign. You're not going to find them organizing against injustices or oppressions. That's just not going to be there.

So in that sense, you have an environment that treats the world as wanting to be racially sensitive but still mostly in a colorblind manner. And that colorblind manner is still indicative of a whole lot of white evangelical churches that want to stay out of the political realm, or at least believe that they're not political.

In south Orange County, you’re going to find professionalized Asian Americans who already a lot of sympathies with white evangelicalism. So the fact that Saddleback had to address an issue reflects not so much of their becoming sensitive, but more with the fact that professionalized evangelical Asian Americans are coming to terms with the pervasive racism that they have faced their entire lives. And rather than excusing it from their churches and from the institutions that they've been a part of, they've become more vocal about confronting that and saying it is not okay.

So I think it still becomes an interpersonal orientation of racial reconciliation, and not really an attempt to address systemic issues of racial justice.

As we look at the end of his career, what do you think Warren's legacy will be? How will he be remembered?

Gerardo Martí: We may still be revisiting the legacy of Rick Warren as we see how white evangelicalism plays itself out in the coming decades.

Certainly, Rick Warren was a part of affirming and further developing the church growth movement. The movement of being able to take a formulaic stance of targeting particular kinds of people, organizing our ministries in particular ways. Staffing them in a way that allows us to have a machinery for being able to attract people, involve them, get them invested and excited about things. Because of Rick Warren and the way he approached church life worked.

Now some people may feel like it didn't give the theological depth that they may want and that it certainly didn't address all kinds of other issues, but fundamentally he was definitely a part of affirming a church growth pattern that was especially successful in expanding suburbanized spaces. And that I think is going to be history.

When it comes to politics, Rick Warren becomes an example of one of many people who believed that politics should work in a particular way. That politics is personal, it has to do with individuals wanting to exercise particular sensitivities, and that we could solve things if we were just reasonable with each other and built relationships with each other. But he did not have an understanding of the vast histories that are embedded in the policies that the country has in the laws that are in our books—dynamics like how the Supreme Court actually works, that racial issues are far more deeply embedded and demand a more radical response.

And finally, I think that when it comes to assessing mega-churches in America, we are still unpacking the meaning and significance of mega church ministry. Mega-churches still remain some of the more unique aspects of American Christianity, and they are still new and are still rare. And whether the future of American Christianity will continue to orient itself around mega-church ministries or whether we'll even see any expansion of mega-churches, that also remains to be seen. But any attention to mega-churches will inevitably include Rick Warren and Saddleback Church.