This piece was adapted from Russell Moore’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

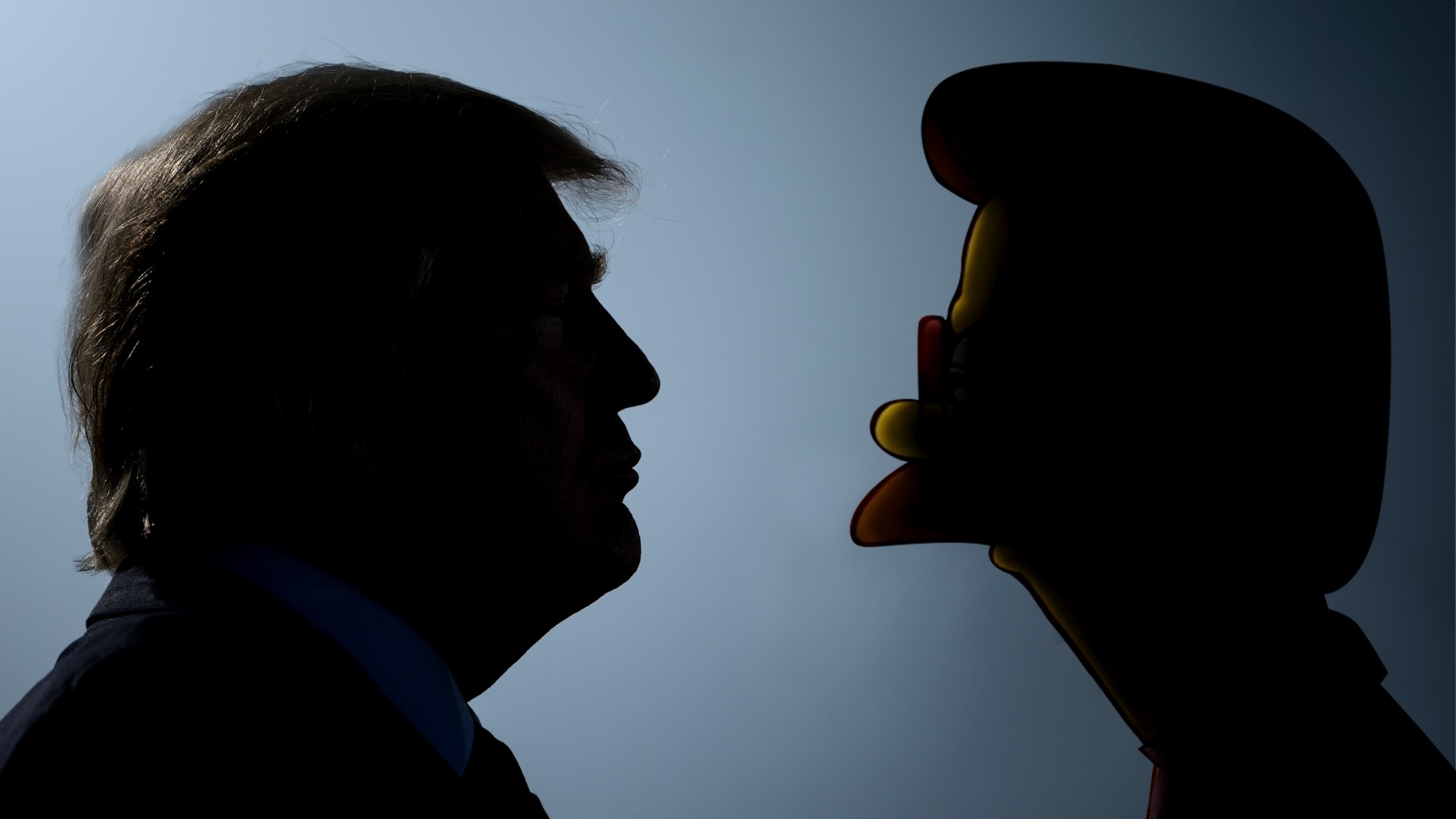

I guess Ned Flanders goes to strip clubs now.

Until this week, I hadn’t thought about the caricatured born-again Christian neighbor on the animated series The Simpsons in a long time. New York Times religion reporter Ruth Graham mentioned him and his “cheerful prudery” as examples—along with Billy Graham and George W. Bush—of what were once the best-known evangelical Christian figures in the country. Indeed, a 2001 Christianity Today cover story dubbed the character “Saint Flanders.” Evangelical Christians knew that Ned’s “gosh darn it” moral demeanor was meant to lampoon us, and that his “traditional family values” were out of step with an American culture this side of the sexual revolution.

But Ned was no Elmer Gantry. He actually aspired to the sort of personal devotion to prayer, Bible reading, moral chastity, and neighbor-love evangelicals were supposed to want, even if he did so in a treacly, ultra-suburban, middle-class North American way. As Graham points out, were he to emerge today, Flanders would face withering mockery for his moral scruples—but more likely by his white evangelical co-religionists than by his beer-swilling secular cartoon neighbors.

As Graham says, a raunchy “boobs-and-booze ethos has elbowed its way into the conservative power class, accelerated by the rise of Donald J. Trump, the declining influence of traditional religious institutions and a shifting media landscape increasingly dominated by the looser standards of online culture.” (This article you are reading right now represents something of this shift, as I spent upward of 15 minutes pondering how to quote Graham’s article without using the word boobs.)

Graham’s analysis is important for American Christians precisely because the shift she describes is not something “out there” in the culture but is instead driven specifically by the very same white evangelical subculture that once insisted that personal character—virtue, to use a now distant-sounding word the American founders knew well—matters.

Yes, part of the vulgarization of the Right is due to the Barstool Sports / Joe Rogan secularization of the base, in which Kid Rock is an avatar more than Lee Greenwood or Michael W. Smith. But much more alarmingly, the coarsening and character-debasing is happening among politicized professing Christians. The member of Congress joking at a prayer breakfast about turning her fiancé down for sex to get there was there to talk about her faith and the importance of religious faith and values for America. The member of Congress telling a reporter to “f— off” is a self-described “Christian nationalist.” We’ve seen “Let’s Go Brandon”—a euphemism for a profanity that once would have resulted in church discipline—chanted in churches.

Pastor and aspiring theocrat Douglas Wilson publicly used a slur against women that not only will I not repeat here but that almost no secular media outlet would quote—and that’s without even referencing Wilson’s creepily coarse novel about a sex robot.

Wilson, of course, cultivates a cartoonishly “Aren’t we naughty?” vibe not representative of most evangelical Christians. But the problem is the way many other Christians respond: “Well, I wouldn’t say things the way he says them, but …” In the same way, they characterize as just “mean tweets” Donald Trump attacking those claiming to be sexually assaulted by him for their looks or war heroes for being captured or disabled people for their disabilities or valorizing those who attack police officers and ransack the Capitol as “hostages.”

What’s worse is that evangelical Christians—including some I listened to pontificate endlessly about Bill Clinton’s sexual immorality (pontifications with which I agreed then and agree now)—ridicule as pearl-clutching moralists those who refuse to do exactly what they condemned Clinton’s defenders for doing, namely, weighting policy agreement over personal character.

In the midst of the late-1990s Clinton scandal, a group of scholars issued a “Declaration Concerning Religion, Ethics, and the Crisis in the Clinton Presidency,” which stated:

We are aware that certain moral qualities are central to the survival of our political system, among which are truthfulness, integrity, respect for the law, respect for the dignity of others, adherence to the constitutional process, and a willingness to avoid the abuse of power. We reject the premise that violations of these ethical standards should be excused so long as a leader remains loyal to a particular political agenda and the nation is blessed by a strong economy.

Those words seem far more distant than a Tocqueville quote now.

Our situation today would be understandable in a world in which words that come out of a person don’t represent what’s present in the heart, or in a world in which external conduct can be severed from internal character. The problem is that such an imagined world is one in which there is no Word of God. Jesus, after all, taught us the exact opposite, explicitly and repeatedly (Matt. 15:10–20; Luke 6:43–45).

Ironically, some of the very people who advance the myth of a “Christian America,” in which the American founders are retrofitted as conservative evangelicals, now embrace a view that both the orthodox Christians and the deist Unitarians of the founding era would, in full agreement, denounce. From The Federalist Papers to the debates around the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, virtually every Founding Father—even with all their differences on the specifics of federalism—would argue that constitutional procedures and policies alone were not enough to conserve a republic: Moral norms and expectations of some level of personal character were necessary.

Do these norms keep people of bad character from ascending to high office? Not at all. Hypocrites and demagogues have always been with us. What every generation of Americans have recognized until now, though, is that there is a marked difference between some leaders not living up to the character expected of them and leaders operating in a space where there aren’t expectations of personal character. You might hire an accountant to do your taxes, only later to find that he’s a tax fraud and an embezzler. That’s quite different from hiring an open fraud because you’ve concluded that only chumps obey the tax laws.

That’s because no leader of any community, association, or nation is an abstract collection of policies. We select leaders to make decisions about matters that haven’t happened yet, or that might not even be contemplated. A dentist who screams profanities at opponents and promises a practice built around “revenge and retribution” and the tearing down of all the norms of modern dentistry is not someone you should trust with a drill in your mouth. How much more so when it comes to entrusting a person with nuclear codes.

Moreover, what conservatives in general, and Christians in particular, once knew is that what is normalized in a culture becomes an expected part of that culture. Defending a president using his power to have sex with his intern by saying, “Everybody lies about sex” isn’t just a political argument; it changes the way people think about what, in the fullness of time, they should expect for themselves. This is what Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously called “defining deviancy down.”

Louisianans defending their support for a Nazi propagandist and former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan because he’s allegedly “pro-life” is not just a “lesser of two evils” political transaction. The words pro-life Nazi—like the words pro-life sexual abuser—change the meaning of pro-life in the minds of an entire generation.

No matter what short-term policy outcomes you then “win,” you’ve ended up with a situation in which some people believe authoritarianism and sexual assault can be offset by the right “policy platform,” while others believe that opposing abuse of power or sexual anarchy must necessitate being opposed to “pro-life.” Either way you look at that, you lose.

What happens long-term with your policies in a post-character culture is important. What happens to your country is even more important. But consider also what happens to you. “If individuals live only seventy years, then a state, or a nation, or a civilization, which may last for a thousand years, is more important than an individual,” C. S. Lewis wrote. “But if Christianity is true, then the individual is not only more important but incomparably more important, for he is everlasting and the life of a state or a civilization, compared with his, is only a moment.”

The Bible not only warns us about what character degradation—from immorality to boastfulness to heartlessness and ruthlessness—can do to the souls of those practicing such things, but also about the ruinous effect on those who “approve of those who practice them” (Rom. 1:32).

Ned Flanders is not, and never was, the Christian ideal. Personal piety and upstanding morality are not enough. But we should ask the question—if The Simpsons were written today and wished to make fun of evangelical Christians, would the caricature be someone inordinately devoted to his family, to prayer, to churchgoing, to kindness to his neighbors, to the awkward purity of his speech? Or would Ned Flanders be a screaming partisan, a violent insurrectionist, a woman-ogling misogynist, or an abusive pervert?

Would that change be because the secular world has grown more hostile to Christians? Perhaps. Or would it be because, when the secular world looks at the public face of Christianity, they wouldn’t dream to think now of Ned Flanders but only of one more leering face at the strip club?

If we are hated for attempted Christlikeness, let’s count it all joy. But if we are hated for our cruelty, our sexual hypocrisy, our quarrelsomeness, our hatefulness, and our vulgarity, then maybe we should ask what happened to our witness.

Character matters. It is not the only thing that matters. But without character, nothing matters.

Russell Moore is the editor in chief at Christianity Today and leads its Public Theology Project.