Tucker Carlson is reviving American interest in Ukraine.

Approaching two years since the Russian invasion on February 24, 2022, the Slavic conflict has been eclipsed by the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza in the forefront of US attention.

Many Americans, however sympathetic they remain, have tired of foreign wars in lieu of pressing domestic issues at home. Others, however, see continued US support for Ukraine as a low-cost check on Russian imperial ambitions.

Carlson, the controversial pundit, is presenting the views of Vladimir Putin.

While many American media outlets have requested an interview with the Russian president, Carlson was granted the interview as his perspective “is in no way pro-Russian, it is not pro-Ukrainian,” stated the Kremlin spokesman. “It is pro-American, but at least it contrasts with the position of the traditional Anglo-Saxon media.”

Carlson said it would allow viewers to see the “truth” obscured by Western reporting.

Christianity Today invited Ukrainian evangelical leaders to comment on any religious remarks conveyed. Seven stated they had no intention to watch what one called a “propagandist” in conversation with “the killer of my people.”

Putin gave them little to work with during the two-hour interview.

“There was nothing new in this interview,” said Valentin Siniy, rector of the Kherson-based Tavriski Christian Institute. “It looks like nothing more than an attempt to play on the feelings of religious freedom in the West.”

But he did, Siniy emphasized, again put forward his oft-repeated Russki Mir (Russian World) ideology.

Putin described the coming of Christianity to Eastern Europe within a nearly uninterrupted half hour answer detailing Russian history, during which he called Ukraine an “artificial state.” Pressed how as a professing Christian he could order violence, Putin spoke only of Russia’s “moral values.” And probing the head of state’s personal faith, Carlson asked Putin if he saw God at work in the world.

“No, to be honest,” the Russian president replied, after a pause. “I don’t think so.”

CT has provided extensive coverage of the Russia-Ukraine war, including descriptions of the polarized American public, Russian-American pastors combating propaganda, and advice for interpreting misinformation no matter the source.

To understand any conflict requires knowledge of its background. CT has published articles about how Christianity came to Ukraine and Russia, the 160-year spiritual history behind today’s divide, and why Ukraine calls upon Michael the archangel. Concerning more contemporary pre-war history, CT covered Ukrainian politics and the efforts of evangelicals to win influence, in addition to the tomos of autocephaly that gave ecclesial independence to one-half of Ukraine’s Orthodox church.

But while Ukrainian sources declined to engage Carlson’s effort to understand the war through the rhetoric of Putin, they have informed most of CT’s ongoing coverage.

As Russia marshaled troops on the border, two articles provided Ukrainian evangelical perspective while waiting in limbo. And after the invasion, two more described the reaction of Christian leaders to their new wartime reality. As the previous Mennonite-inspired pacifism of Ukraine was pushed aside in defense of the homeland, reporting also provided the response of the foreign missionary community. Subsequent articles described ways in which concerned Christians can help.

An immediate need was with the millions of refugees dispersed around the world. CT’s June 2022 cover story featured this issue, with other reporting zooming in on the evangelical response in Moldova, among believing Roma minority communities, and among Slavic churches in the US. Coverage was also given to the controversial reception Ukrainian refugees received in Russia.

One of Carlson’s objectives is to present Americans with Russian perspective. CT has consistently aimed to do similarly through the Russian evangelical church. While many sources requested to shield their identity to avoid prosecution under Russian law—such as in making a theological case for peace—one Russian leader offered Ukrainians a public apology.

But the need for security was real. One Russian pastor spoke out against the war and was forced from his church. A prominent Russian Baptist leader fled into exile prior to his arrest. Early reports about hundreds of Russian clerics opposing the invasion further developed into an article about overall Russian Christian opinion of the “special military operation.”

CT then asked five European evangelical leaders whether Russia needed more “Bonhoeffers.”

Europe was not the only region impacted by the war, even as evangelicals in Russian-allied Belarus feared greater isolation. Christian leaders debated if the welcome extended to Ukrainians signaled racism toward rejected Syrians and other Muslims. Taiwanese wondered that if Russia was not pushed back, China might similarly invade them. Israel dealt with an influx of Jews from both Russia and Ukraine, while a seminary in Estonia did its best to reconcile believers.

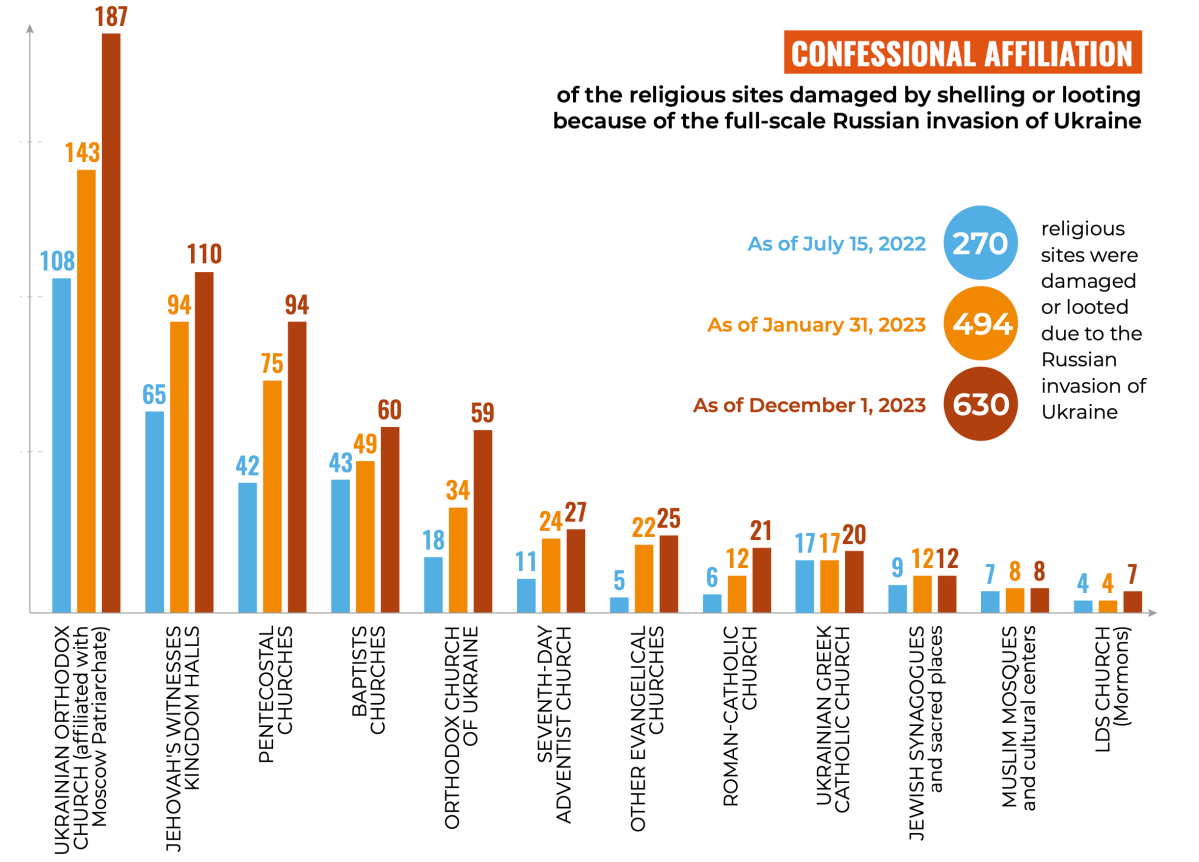

But primary CT coverage followed the wartime prayers and favored verses of Ukraine’s evangelical community, the impact of destruction upon seminaries and churches—first tallied at 500 religious sites, then updated last month to 630 sites—and the ministry they continued nonetheless. As evangelical women and seminarians pleaded for help, the toll of war was described in Irpin, Bucha, and Kherson.

And as CT’s February 2023 cover story featured how evangelical leaders were ready to “meet God at any moment,” a photo essay provided a window into the life of frontline chaplains. Service continued in Ukrainian Christian schooling, prison ministry—including to Russian POWs—and radio outreach, despite restrictions on use of the Russian language.

Such restrictions have often been highlighted by commentators like Carlson, with particular emphasis of those recently enacted and threatened against the Moscow-linked Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC). CT covered the UOC’s initial efforts to signal its independence from Russia, and the local reactions as Ukraine threatened and then recently passed a law that allegedly would “ban” the historic denomination altogether.

Amid the controversy, Ukraine switched its Christmas celebration from the traditional Orthodox date of January 7 to the Western date of December 25. A holiday-themed article described the Ukrainian origin of Carol of the Bells, while an Easter article featured the Ukrainian Pysanky eggs.

But while most of CT’s reporting aims to reflect nuance in its presentation of the mutual recriminations, coverage has also sought to faithfully convey evangelical perspectives, as offered in “Christmas Epiphanies from the Ruins of Ukraine.”

God may have been minimally invoked during the Carlson-Putin interview. But even as Ukrainian evangelicals struggle to make sense of their national ordeal, they keep God at the forefront (as seen in Ukraine’s top 10 Bible verses last year). One emphasized after the interview released late Thursday that he is praying for victory.

“I relate to the Psalmist’s prayers for delivery from the evil deeds of evil men, and many biblical examples give me hope,” said Maxym Oliferovski, a Mennonite Brethren pastor and project leader for Multiply Ukraine. “But even if he doesn’t I will continue to praise him, for God is good and sovereign.”