One author once said that in the hearts of many Christians, the Chinese Union Version (CUV) Bible is “the only Chinese Bible; everyone calls it the ‘Chinese Bible’ and not the CUV.”

Another praised the CUV as “a collection of the essence of a hundred years of Bible translation,” a “culmination of the efforts of countless Chinese and Western scholars, with many terms derived from [Robert] Morrison’s translation.”

Although there have been several high-quality Chinese translations in recent years and the CUV has undergone revisions, the early history of Protestant Chinese Bible translation clearly testifies to Chinese-Western cooperation and global collaboration, laying the foundation for different Chinese translations in the future.

The Bassett Version and the first translations

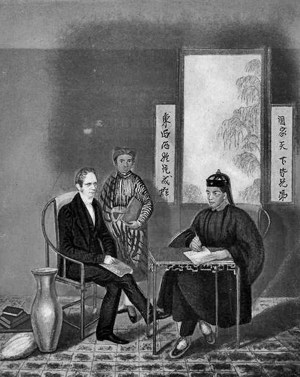

When Robert Morrison arrived in Guangzhou in 1807, China operated under the Canton System, restricting foreigners’ activities to the port of Guangzhou and imposing limitations on their interactions with the Chinese.

During his studies and translation work, Morrison heavily relied on a copy of the New Testament known as the British Museum Manuscript, which he acquired from his Chinese teacher, Yong Sam-tak, in London. This manuscript was later identified as a translation of the New Testament done by French missionary Jean Bassett and Chinese believer Johan Su (or Xu) in Sichuan. However, Bassett’s translation reached only the first chapter of Hebrews before his death in 1707, leaving the task unfinished.

This copy significantly influenced Morrison’s translation efforts and created a competitive environment with another group of Protestants attempting to translate the Bible into Chinese in Serampore, a Danish-controlled port in northeastern India.

The mission center in Serampore, founded by Baptist missionary William Carey, made significant contributions to India. Alongside their missionary work, they engaged in poverty alleviation, education, and the translation and printing of the Bible in multiple Indian languages. Through an unexpected encounter, they met a Chinese-speaking Armenian named Joannes Lassar (original name Hovhannes Ghazarian), which led to the expansion of their ministry in Chinese Bible translation.

Lassar can be considered a member of the Canton System Era. His father was a businessman who had brought his family to China for trade. However, at that time the Thirteen Factories area in Guangzhou allowed only foreign merchants and business personnel (such as translators, which was a position Morrison also had to take on to stay in China) to reside there, so Lassar’s father had to leave him in Macau and hire a Chinese teacher for him to learn the language. Later on, Lassar faced some business failures and ended up living in India. Through a series of events, he was invited by believers in Serampore to teach Chinese and began collaborating with Baptist missionary Joshua Marshman in translating the Chinese Bible.

While Morrison was still in the early stages of his translation work, Lassar and Marshman had already published their translations of the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Mark in 1810–1811. Under intense competition, Morrison sought to expedite his progress and heavily relied on Bassett’s manuscript, eventually completing the translation of the entire New Testament in 1813. Upon learning of the existence of the Bassett version, the Baptist translators in Serampore used it to revise and complete their own translation. Consequently, both translations (collectively referred to as the Two Ma Versions, namely the Morrison and Milne version and the Marshman and Lassar version) were influenced by the Bassett version, resulting in significant similarities in terminology.

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsSince Bassett’s version covered only up to the first chapter of Hebrews, Morrison, Marshman, and others had to translate the remaining portions of the New Testament and the entire Old Testament by themselves. However, many key terms from the Bassett version have continued to be used to this day, testifying to its enduring influence. These terms include gospel, apostle, righteousness, grace, salvation, kingdom of heaven, prayer, and the profoundly influential term God.

Experience of missionary work in Southeast Asia and localization of the Bible

Due to the primary translation programs of the Two Ma Versions taking place in the relatively closed foreign quarters of Guangzhou and Serampore, there were limited opportunities for Chinese readers to participate and provide feedback. However, this situation began to change before the completion of the Two Ma Versions. William Milne, who was also part of the London Missionary Society, established a mission base in Malacca, Malaysia, in 1815, following Morrison’s suggestion. He gradually discovered that several Chinese communities in Southeast Asia were significant fields that could greatly contribute to the development of local and Chinese evangelistic work.

Other missionaries who arrived in Southeast Asia to carry out their work included Walter Medhurst from Britain and Karl Gützlaff from Germany. These missionaries had more opportunities to engage with the local Chinese population in Southeast Asia. They even used various written media to introduce people to the Christian faith, including novels, magazines, and gospel pamphlets. To reach a wider readership, these reading materials were often written in a simpler and more accessible style known as Easy Wenli, the vernacular language of Ming and Qing dynasty novels.

As translators, the missionaries realized that the language used in the original translations of the Bible was too literal and not smooth for Chinese readers. Although Morrison’s translation of the Old and New Testaments, Shen Tian Sheng Shu (The Holy Book of God and Heaven), was a joint effort with Milne, Milne joined in only during the translation of the Old Testament, making it difficult to make significant changes to the language and style of the version.

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsAfter Morrison died, Medhurst and Gützlaff had the opportunity to retranslate the Bible by using a more localized language and vocabulary. The completed New Testament version was commonly known as the Four Men’s Translation—a collaborative effort by Medhurst, Gützlaff, Elijah Coleman Bridgman (the first American Protestant missionary to China), and Morrison’s son, John Robert Morrison (who was born in Macau).

Leading the team, Medhurst not only utilized a more colloquial style of vernacular language but also attempted to replace some of the more phonetically translated terms in the Shen Tian Sheng Shu with more authentic and meaningful expressions. For example, [口撒]咟日 (Sabbath) was changed to 安息日; 吧[口所][口瓦]日 (Passover) was changed to 逾越節; and 啦吡 (Master or Teacher) was changed to 夫子. Another significant change was replacing the word 言 with 道 in chapter 1 of the Gospel of John, introducing the concept of 道 (the Way) that already existed in Chinese philosophy into Christianity. It is believed that this more authentic translation and writing method was related to the missionaries’ experiences and interactions with Chinese people in Southeast Asia.

The Four Men’s Translation ultimately did not receive support from the British and Foreign Bible Society, but Gützlaff completed the translation of the entire Old Testament in the same style on his own. This combined Old and New Testament version was later selected by Hong Xiuquan and became the basis for the Bible of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom.

Collaboration of East and West: Classical Chinese translations

In the mid-19th century, due to various unequal treaties, China gradually opened multiple ports and inland regions to foreigners. As a result of this significant political change, the translation work of the Protestant Bible in China moved toward two new but different directions.

First, with the increasing number of missionaries in different regions, there was a growing call for a unified translation that could be accepted by everyone. Yet this noble idea was easier said than done. In 1843 a missionary conference was held in Hong Kong, where it was decided to appoint delegates from different regions to jointly translate a united Delegates’ Version (委辦譯本) of the Bible.

However, disputes arose among the translators, including the more dominant representatives from the London Missionary Society, such as Medhurst, leading to disagreements that extended even to among nations. The areas of dispute included the translation of certain terms, with the most serious issue being the choice between 上帝 (Shangdi, “God”) and 神 (Shen, “God”)—a controversy that would continue for many years and become the catalyst for the ongoing issue of how to translate the divine names.

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsAnother point of contention was the written language used in the translation. Medhurst believed that a unified translation using classical Chinese (later known as High Wenli) would earn the respect and attention of Chinese intellectuals. However, American missionaries, led by Elijah Coleman Bridgman, preferred a more colloquial and easily understandable novelistic style (later known as Easy Wenli).

Due to the unresolved dispute, only the New Testament portion of the Delegates’ Version was completed. Subsequently, the British missionaries withdrew from the committee and translated the Old Testament by themselves. Meanwhile, American missionaries Bridgman and Michael Culbertson embarked on their own translation of the Bible, using what they deemed appropriate translated names and written language. This Bridgman-Culbertson version did not gain much popularity in China, but it caught the attention of American missionaries in Japan and even influenced the subsequent translation of the Japanese Bible.

Regarding the Delegates’ Version, the British missionaries faced challenges in using the hard-to-understand classical Chinese to produce a translation that Chinese intellectuals would accept. Fortunately, Medhurst’s team received assistance from the Confucian scholars Wang Changgui (王昌桂) and his son Wang Tao (王韜), which enabled them to successfully complete the translation of the Delegates’ Version. Medhurst praised Wang Changgui for his extensive knowledge, which earned him the reputation of a “living dictionary.” He described Wang Tao as less knowledgeable than his father but possessing a keen and skillful application of language, with elegant style and sound judgments.

Renowned historian and educator Luo Xianglin later described the text of the Delegates’ Version as having “elegant expressions, rich literary qualities.” The success of Medhurst’s classical Chinese translation owed much to the contributions of Wang Changgui and Wang Tao, the two Chinese translators.

The emergence of colloquial translations

Another development in the translation of the Chinese Bible can be seen as a shift in the opposite direction from classical Chinese translations. As missionaries were able to travel to various parts of China, they began to understand the diversity of the Chinese language and the low literacy rates among the people. Many of the target audiences, such as women, could not understand classical Chinese, and even if the Bible was read to them, they could not comprehend it. Missionaries began to explore the possibility of translating the Bible into colloquial (vernacular) language, hoping that when it was read, the people would have a better understanding.

They also discovered significant differences in the languages spoken in various regions of China, necessitating the use of different vernacular versions to cater to local needs. For example, Mandarin was needed in the northern regions, while the Suzhou and Shanghai dialects were needed in the Jiangnan area, and Hokkien and Cantonese versions were needed in the southern coastal regions.

These versions were all translated using Chinese characters. Additionally, some versions were translated using Romanized phonetics, including the early German Lutheran missionaries Wilhelm Louis and Ernst Faber’s Romanized Cantonese version of the Gospel of Luke in local vernacular colloquial, as well as the Hakka Bible translated by the Swiss Basel Mission (now known as the Tsung Tsin Mission). These versions were mainly produced to facilitate missionaries’ reading.

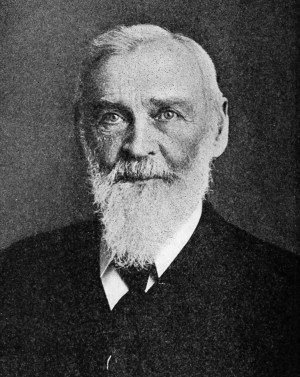

The first and most famous Mandarin translation was the Beijing Version of the New Testament, which was jointly translated by several missionaries working and preaching in Beijing, including William A. P. Martin, the head of the Tongwen Guan (Imperial College), and the Jewish American missionary Samuel I. J. Schereschewsky.

Since Schereschewsky came from a Lithuanian Jewish family and had studied in rabbinical schools from a young age, he had a deep understanding of Hebrew. After the release of the Beijing Version, he translated the Old Testament using both Mandarin and Easy Wenli. His Mandarin version of the Old Testament and the Beijing Version had a significant influence on the later Mandarin Union Version. Many of the beautiful and accurate translations in the Union Version, such as Psalm 23, bear Schereschewsky’s translation traces.

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsEmbracing differences in a collective translation

In 1890, during another missionary conference in China, missionaries from various countries and the Bible Societies of England, America, and Scotland jointly decided to establish three translation committees to work on a new collaborative version. This translation was characterized by its diversity, with one translation but multiple versions that aimed to address major controversies in the translation of the Chinese Bible over the years.

For example, they accepted the usage of both Shangdi and Shen to overcome the issue of translating God’s name, and they allowed both baptism and washing to be used to eliminate translation differences between the Baptists and other denominations. In addition, they used classical Chinese (High Wenli), novelistic style (Easy Wenli), and vernacular (Mandarin) simultaneously in translation to resolve disagreements regarding the choice of written language.

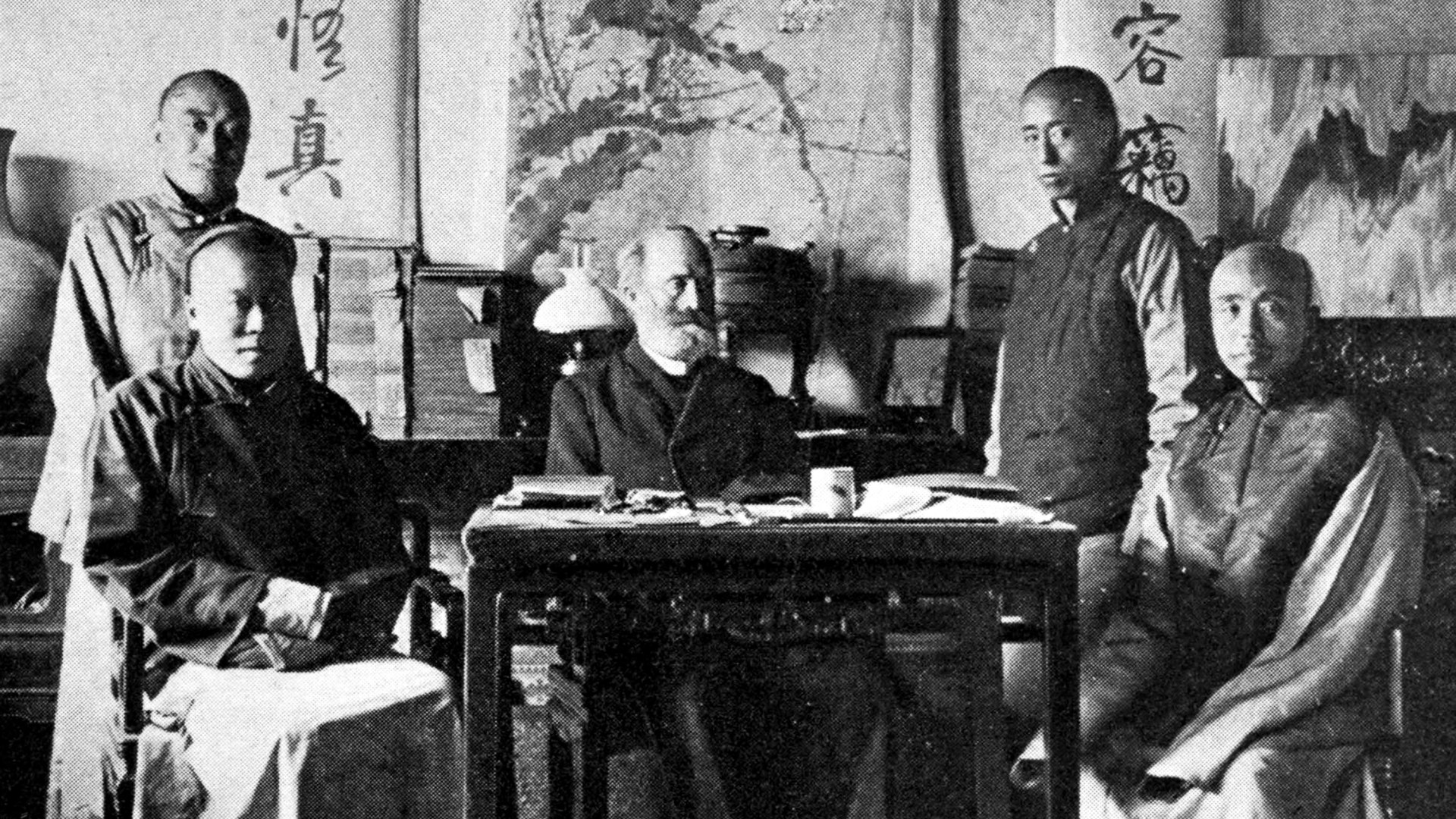

The Union Version gained widespread support within the church shortly after its release, largely due to the underlying spirit of seeking unity despite differences and the willingness to compromise. Additionally, although the majority of members in the translation committees for classical Chinese, Easy Wenli, and Mandarin were missionaries from the United States and England, Chinese members also played an important role.

Evidence of Chinese translators can be seen in photos of various Union Version translation committees, and Wang Xuanchen (王宣忱, also known as Wang Yuande 王元德), a colleague of Calvin Wilson Mateer, was an especially significant participant. Not only did Mateer regard him as a “good teacher,” but after the completion of the Union Version, Wang Xuanchen also independently retranslated the New Testament to improve the text’s fluidity and published his own complete New Testament in 1933. Although this translation had limited circulation, Wang Xuanchen witnessed the unique features of the collaborative Chinese Bible translation work between the East and the West over the years. The Union Version that we still use today is undoubtedly a collaborative achievement of missionaries and translators from multiple countries.

Clement Tsz Ming Tong is a lecturer of biblical studies and biblical languages at Trinity Western University of Canada and a lecturer of Chinese and East Asian history at UBC and Kwantlen Polytechnic University of Canada.

This article is part of a series commemorating the bicentennial anniversary of the publishment of the Morrison-Milne Holy Bible in Chinese translation jointly organized by the British & Foreign Bible Society and CT.