Over 40,000 people gathered at Cairo’s famed cave churches this month for perhaps the largest Christian funeral service in Coptic Orthodox history.

They honored Egypt’s beloved Abouna (“Father”) Samaan, founder of St. Simon the Tanner Monastery, who passed away October 11 at the age of 81.

His renown, however, stretched far beyond Egypt to include many luminaries in the Western evangelical world. And over the course of Abouna Samaan’s life, their endorsement helped popularize his “Garbage City” outreach, to the extent that Tripadvisor counts its Scripture-carved walls and chiseled biblical panoramas alongside museums, mosques, and the Nile River as one of the ten must-see sites in Cairo.

The black-robed and white-bearded priest was born in 1941 with the birth name of Farahat Ibrahim. An otherwise ordinary Egyptian Christian, he worked as a typesetter at the printing press of St. Mark’s Coptic Cathedral. Over time, he came to know the Lord in a personal way through the Society for the Salvation of Souls, a Coptic revivalist group that chooses to remain in the Orthodox church while reaching the unreached with the gospel.

Farahat became a diehard evangelist, urging an individual conversion to Christ.

In 1972, the newly married typesetter led Qidees, his neighborhood garbage collector, to the Lord. The young couple lived in Shubra, a Coptic-majority neighborhood of Cairo, and Qidees transported the area trash 13 miles east to a shantytown at the foothills of Egypt’s Mokattam Mountains. Three years earlier, a community of very poor Christians had migrated from Upper Egypt in search of a better life and eked out a living recycling useful waste and feeding pigs with the edible remains.

Muslims consider pigs unclean, so Garbage City consisted only of nominal Copts.

Like Qidees, most of these Christians had almost no knowledge of the Bible, with no church or pastoral care in their disease-infested slum. Many were alcoholics and drug addicts, and sometimes very violent. But after two years of discipleship, Qidees asked Farahat to visit and evangelize his family.

Farahat’s first reaction was fearful repugnance—but he went anyway.

By then 14,000 Copts populated the area, and after a few months, Qidees’ wife and seven children and many of their neighbors came to the Lord. Their weekly meeting soon outgrew its reed-roofed tin hut, and as numbers increased, Farahat convinced his well-off friends from the Society of the Salvation of Souls to build them a small church.

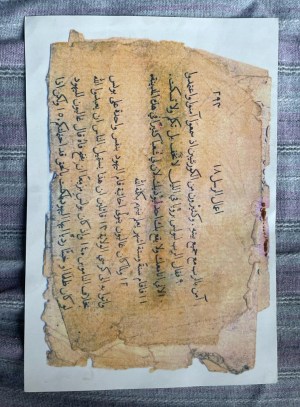

The people wanted him to become their priest. Reluctant, Farahat spent several nights in a small cave above the garbage village in prayer. As he was doing so, a scrap from an Arabic Bible blew by, torn from Acts 18. I am with you, and no one is going to harm you, he read, because I have many people in this city. He took this as God’s call to become their pastor.

Ordained in 1978, the young priest took Samaan—“Simon” in English—as his clerical name from a celebrated saint from Coptic lore who, as a simple tanner, worked a miracle in the same Mokattam mountains. But his early years were very difficult. Trudging through overflowing trash heaps with a pair of boots and a flashlight, one would-be disciple attacked him with a knife, another hid from the priest in a pigsty. There were no social programs in the area—only the flickering gleam of the Good News of Jesus.

Courtesy of Mariusz Dybich

Courtesy of Mariusz DybichBut as hundreds came to know the Lord, they also realized their dignity as children of the Creator of the universe. Over time, the whole village changed. Though still smelly, filthy, and garbage-infested, it became a unique island of Christian faith in Muslim-majority Cairo. By the early 1990s, it had grown to 70,000 inhabitants, as Christians from other areas favored a like-minded religious ethos over the discomfort they felt with their Muslim neighbors.

Shops opened, recycling factories were established, and the community mobilized to demand paved roads, water, electricity, and sewage treatment from the government. Today over 90 percent of the trash in Garbage City—now known as the recycling capital of Egypt—is reused, and NGOs market creatively designed garbage-turned-crafts.

The physical changes were dramatic. But the real change was in their hearts. Money no longer spent on alcohol or drugs was used to improve family life. Rather than living in one-story shacks shared with animals, residents built apartment blocks to live above the corralled livestock and collected garbage. And many centered their new life around the active and growing church.

My American wife Rebecca, born to missionaries to Haiti, first met Abouna Samaan in 1982. He told her of his difficulty evangelizing the illiterate and of his hope that the children could learn about and then read the Bible to their families.

From then on, she joined the fledgling church school project, and still volunteers twice a week at the now eight-story Center of Love for youth and special needs children. Early flannelgraph stories in the first school classroom were supplemented by the academic focus of her friend Laila Iskandar, who went on to serve as Egypt’s minister of environment and later as minister of urban development. Today both the church school and childrens’ center have mostly paid staff, who together have helped educate a generation of Bible-loving Egyptian Christians.

Western evangelical leaders lauded Abouna Samaan’s devotion to God and biblical knowledge.

“I was so impressed by [his] love of Scripture,” said Lindsay Olesberg, chair of Wycliffe USA. “I remember him telling our group that he was daily dependent on being fed by the Word.”

John Piper, chancellor of Bethlehem College and Seminary, noticed the same.

“I remember him sitting at the head of a long table, Bible open before him,” he said. “We sat sipping the juice he provided and feasted on his brief devotional.”

Courtesy of Mariusz Dybich

Courtesy of Mariusz DybichAbouna Samaan held a regular Thursday evening service for the local community but imparted his biblical values through personal engagement and many teaching sessions throughout the week. Once, a then-atheist American visitor unknowingly dropped his Rolex watch, which was returned to him by a poor garbage-collecting child. Flabbergasted, he told the child its cost and how, if he had kept and sold it, it would have transformed his entire life.

The boy replied that it would have displeased his Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.

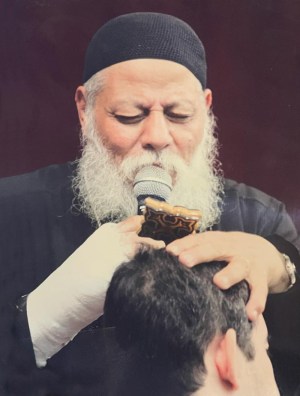

In addition to Bible teaching and social work, once a week Abouna Samaan included a service of exorcism and healing. Christians (and some Muslims) came by the hundreds for prayer and deliverance, whether physical or spiritual.

“He had absolute confidence in the spiritual authority of every believer in Christ,” said Paul Williams, CEO of Bible Society UK, “over all the works of the enemy.”

Foreign awareness of the Garbage City ministry took off in 1990, when the first cave was converted into an auditorium seating 3,000 people. Rebecca and I marveled as rich and poor alike would navigate the pungent smells to reach the auditorium and worship together.

All of Egypt’s Christian denominations were welcome.

Ever expanding in service and rock-hewn beauty, the peaceful oasis now contains six cave churches and a 25,000-seat cathedral. Nearby is the special needs center and an 11-story state-of-the-art hospital. And 80 miles east, Abouna Samaan established a thousand-guest conference center in Wadi al-Natroun, on the desert road between Cairo and Alexandria.

Many evangelical leaders praised his ministry:

- “He is someone we can truly call a hero of faith,” said his close friend Sameh Maurice, pastor of Kasr el-Dobara Evangelical Church in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. “He renounced his life by living among and serving the garbage collectors as one of them, to gain thousands and thousands for Christ.”

- “What struck me most was that here was a man who cared for the least of these of whom Jesus spoke,” said Lindsay Brown, former director of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. “A man who had two loves: the Christ of the gospel, and all people—especially the people of the streets.”

- “When I first visited the garbage village, the sights and smells and suffering overwhelmed me,” said Doug Birdsall, honorary chairman of the Lausanne Movement. “But when I met him, I was even more overwhelmed—this time with the love and compassion that I saw in his eyes, and with the aroma of Jesus … so much so that I did not want to leave.”

But all this came at a price, much more than the many financial, logistical, and legal challenges that he encountered in developing his extensive ministry. After becoming well-known and beloved by many, Abouna Samaan was opposed by some leaders in the Coptic hierarchy who accused him of “Protestant” tendencies. These accusations greatly discouraged him and his flock.

Humanly speaking, he only survived through his close friendship with Shenouda III, patriarch of the Coptic Orthodox Church. Their relationship began in the cathedral printing press, as Pope Shenouda was a prolific writer and publisher.

But after the Coptic patriarch passed away in 2012, a special diocese was created for the area, with a bishop appointed to oversee the monastery complex and several other local churches. Unfortunately, Abouna Samaan and the new bishop did not agree on many issues, impacting the latter years of his life.

Over these many years, Rebecca and I recognized Abouna Samaan’s ministry as a miracle of God, accomplished from very humble beginnings. We know of no other Christian endeavor—in Egypt or elsewhere—with which to compare it. A simple typesetter impacted the lives of hundreds of thousands of Coptic believers, ministered to Muslims, and brought many to the Lord.

And at the funeral, the Coptic Orthodox church honored his service. With tears in his eyes, Bishop Youannis, a leading member of the Holy Synod, delivered a remarkable eulogy in appreciation for Abouna Samaan’s ministry. Before the thousands looking on, the bishop recounted the life of his longtime friend, giving the praise and glory to God.

“If this historic gathering is your sendoff,” he stated, “I wonder what your welcome in heaven was like.”

Ramez Atallah was general secretary of the Bible Society of Egypt from 1990–2021 and currently serves as its senior advisor.