“Bigger!” said the voice in my in-ear monitor.

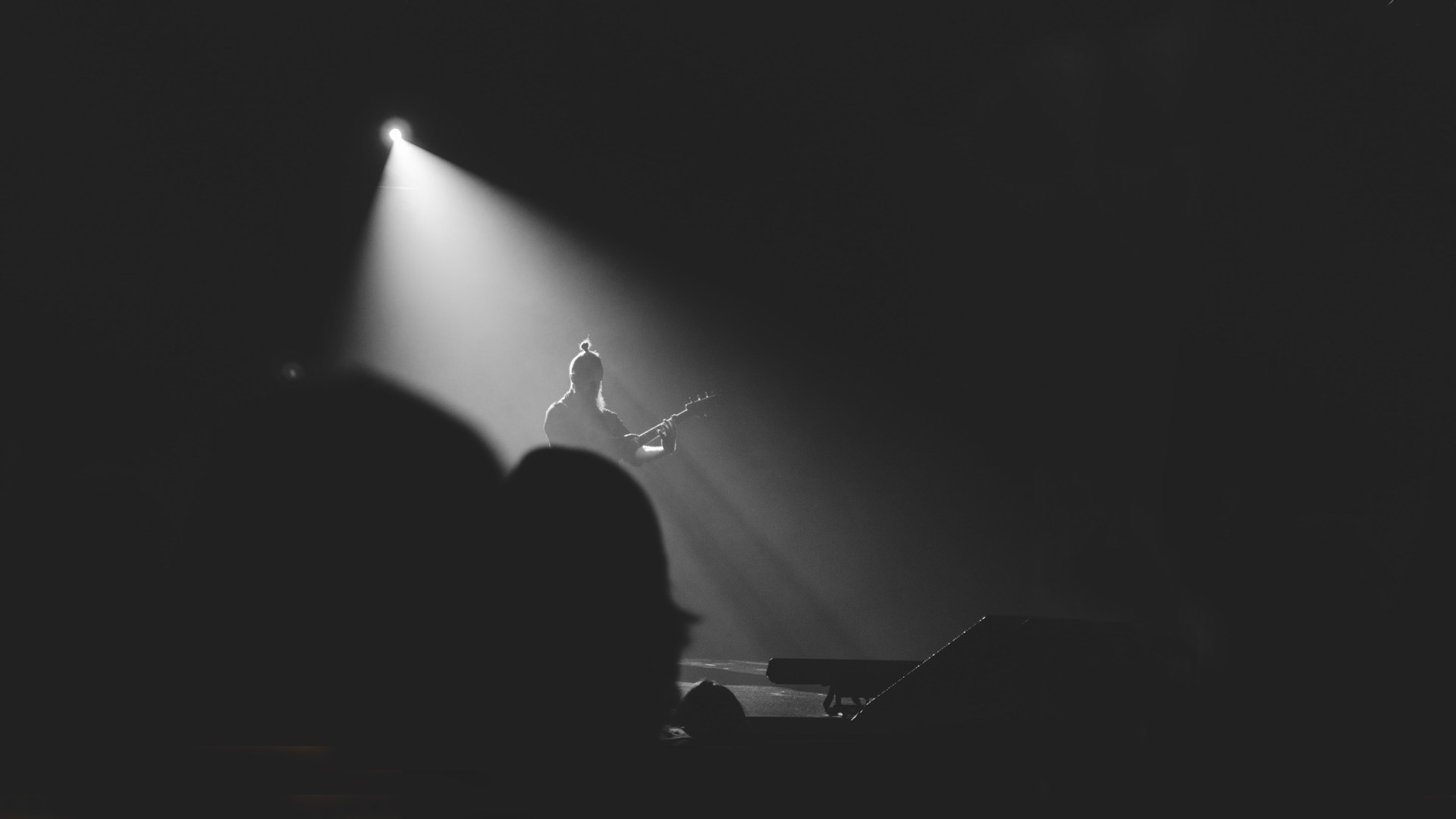

I was on stage in a dark room, nearly blinded by spotlights. It was my first time leading worship at a big regional conference for college students, and one of the production managers in the sound booth prompted me to raise my hands higher, move more, clap more, jump, be more physically demonstrative.

I had always known conference worship sets were orchestrated, but this was the first time I could see the minutiae. At one point, I was told to imagine my arms attached to foam pool noodles, to keep them straight and raise them high. Each song was ranked by “energy level” from 1 to 5, and certain sessions could have songs only above a 3.

I remember wondering, Am I manipulating the people watching, singing, and listening? Am I using music to generate an emotional response in the crowd?

The short answer is yes. Worship music can move and manipulate emotions, even shape belief. Corporate worship is neurological and physiological. Martin Luther insisted that music’s ability to move and manipulate made it a singular, divine gift. “Next to the Word of God,” Luther wrote, “only music deserves being extolled as the mistress and governess of the feelings of the human heart. … Even the Holy Spirit honors music as a tool of his work.”

Songwriters and worship leaders use tempo and dynamic changes, modulation, and varied instrumentation to make contemporary worship music engaging, immersive, and, yes, emotionally moving.

As worshipers, we can feel it. Songs with lengthy interludes slowly build anticipation toward a familiar hook. Or the band drops out so voices sing out when the chorus hits. Plus the lyrics themselves can cue our behavior (“I’ll stand with arms high and heart abandoned”).

There are valid and interesting questions about the particularities that give contemporary worship music its resonance—borrowed conventions of secular love songs and pop ballads or associations with the aesthetics of high-energy arena rock concerts by artists like U2 and Coldplay, for example. But current concerns about the manipulative power of worship music seem to have less to do with musical style and taste than with the people and institutions involved in the making and performance of it.

So perhaps the question I should have been asking myself on stage is not whether the music was manipulative but whether those of us responsible for the worship set were trustworthy stewards and shepherds of the experience.

Corporate worship invites us to open ourselves to spiritual and emotional guidance. That openness feels, and is, vulnerable. And as worship becomes a bigger production in churches and ministry events, a rising chorus has challenged whether our emotions are in safe hands.

“That’s the tricky thing about emotions. [In musical worship] something happens inside you that is both voluntary and involuntary,” said ethnomusicologist Monique Ingalls, who directs graduate and research programs in church music at Baylor University.

Worshipers have agency; they decide how much they open themselves to emotional direction. Even extreme examples of musical propaganda require receptivity on the part of the listener. Musical propaganda is most effective when the music is used to increase devotion—to build on our faith—not change or alter beliefs. But once there is trust and buy-in, a dangerous, exploitative emotional manipulation is possible.

“Emotional manipulation in a worship service is like a shepherd leading people to certain pastures without knowing why,” wrote Zac Hicks, author of The Worship Pastor, on the subject of “manipulation vs. shepherding.”

“Manipulation, at its best is ‘purposeless shepherding,’ or ‘partial shepherding,’” Hicks wrote. “A sheep-person waking up from the fog of manipulation will often first exclaim, ‘Wait, why am I here?’”

Rather than a worship leader seeing the crowd’s emotional response—raised hands, closed eyes, or tears—as a sign of a successful set, Hicks argued that a thoughtful shepherd will use what he calls the “emotional contours of the gospel” (“the glory of God,” “the gravity of sin,” and “the greatness of grace”) to shape musical worship and avoid manipulation.

But when worshipers suspect that attention to the gospel’s contours has been superseded by other influences, trust begins to erode. Does it seem like the worship leader on stage is concerned more with cultivating a particular image than with serving in a pastoral role? Do heavy emotional moments seem to become overtures to fundraising? Worshipers fear manipulation when they have a reason to doubt the intentions of a leader or institution.

“It’s easy to mistake emotional manipulation for a movement of God, right?” journalist and author Kelsey McKinney said in the 2022 documentary Hillsong: A Megachurch Exposed. “Are you crying because the Lord is staging some kind of intervention in your life, or are you crying because the chord structure is built to make you cry?”

The suspicion that a chord structure might be “built to make you cry” oversimplifies the relationship between music and emotion. Music does not simply act upon the listener; there is a dialectic between an individual and music in which each influences and responds to the other.

But the fear of being tricked into perceiving carefully crafted music as a spiritual encounter is understandable when it seems like powerful people at the helm of megachurches are using powerful music to cultivate loyalty and devotion—not only to God but also to their brand.

Scandals like the ones that have plagued Hillsong in recent years, as well as indications that contemporary worship music is increasingly shaped by financial interests, are feeding skepticism. A growing share of the worship music used in churches comes from a small but powerful group of songwriters and performers that most of us will never see in person.

When it comes to emotional shepherding, Ingalls sees trust and authenticity as paramount—two things that are difficult to maintain in a celebrity-fan relationship.

“I think the fear of manipulation, the question ‘Can I trust this person?’ is absolutely wrapped up in the authenticity debate,” Ingalls said.

But concerns around emotional manipulation far predate Hillsong and the worship mega-artists of the past 20 years. A 1977 Christianity Today cover package titled “Should Music Manipulate Our Worship?” called out new expressions marked by “a strong beat and a high emotional pitch,” from uptempo “gospel rock” bands.

The musical styles have changed, but the direction offered remains relevant for today:

If the evangelical church is to respond maturely to the swiftly changing patterns of musical expression, we need trained, concerned ministers of music who can guide us past the pitfalls of both aestheticism (worship of beauty) and hedonism (worship of pleasure).

We need musicians who are first ministers. They must understand the spiritual, emotional, and aesthetic needs of ordinary people and help lead a church in its quest for the true Word and for a creative, authentic, and complete expression of its faith. This kind of a ministry is more concerned with training participants than with entertaining spectators.

Imperfect medium, imperfect shepherds

C. S. Lewis, though not a musician, professed the belief that music could be “a preparation for or even a medium for meeting God,” with the caveat that it could easily become a distraction or an idol.

Musicologist John MacInnis has observed that Lewis’s exposure to the music of Beethoven and Richard Wagner was a spiritual gateway. Lewis considered transcendent musical moments in his life as signposts and would look back after his conversion to Christianity and see them as encounters that moved his heart and mind toward God.

But Lewis recognized the imperfection of music as a mode of worship or devotional meditation. “The emotional effect of music may be not only a distraction (to some people at some times) but a delusion: i.e. feeling certain emotions in church they mistake them for religious emotions when they may be wholly natural.”

Lewis did not understand his response to Wagner’s Ring cycle as worship, but he felt it brought him to some form of transcendence, to an overwhelming sublime encounter.

Listeners overwhelmed by the visual and sonic spectacle of a Taylor Swift concert might feel euphoria that does indeed surpass the usual scope of their emotions. Music and its contexts can bring us to the height of our emotional capacities. We can be overwhelmed by its beauty or power, by the visual media it accompanies, by a memory it alone can activate with precision and potency.

Like Lewis, perhaps we all can benefit from allowing ourselves to be overwhelmed by music outside the sanctuary every now and then. It may be that understanding our capacity to be moved by music will help us navigate our emotional openness in worship.

The exact workings of music on the emotions are inscrutable, even with new neurological research that further explores music’s effects on the brain. Beneath our fear of being emotionally manipulated, for most of us, lies a fear that we are being coerced into doing or believing. We fear that our emotions are responding only to the music and not to the Holy Spirit, that what we perceive as a spiritual encounter is counterfeit, manufactured by skillful musicians, a production team, and a well-written musical hook.

Transparency may be one antidote. It may help for musicians and worship leaders to simply be more open about the ways they program music or what the purpose of a particular musical selection might be. A leader might preface a meditative song with intimate lyrics by encouraging the congregation to consider a passage of Scripture. Just acknowledging the emotional weight of the moment indicates self-awareness and care on the part of the leader.

Ingalls suggests evaluating emotional musical worship experiences in a particular church or ministry by looking at the fruit of that worship outside the sanctuary. “When we're evaluating emotions in worship, we can ask, ‘What are the worshipers that have these intense emotional experiences going out and doing?’”

If we accept that our moving, sometimes tearful, moments in a singing congregation are almost always brought about by some cooperation between God in us and the music around us, we can keep an eye on the work of our shepherds by looking around at the pastures where we find ourselves on the other side.

“What is being done on the ground?” Ingalls suggests asking.“To bring God’s shalom into the world? To heal broken relationships between God, between people, between people and the earth?”

Kelsey Kramer McGinnis is CT’s worship music correspondent. She is a musicologist, educator, and writer who researches music in Christian communities.