Jackie Robinson, the first African American to play in the modern era of Major League Baseball (MLB), is undoubtedly one of the most significant cultural figures in the history of professional sports. Fittingly, his remarkable life has inspired a number of excellent books aimed at diverse audiences.

The starting point for reading about Robinson ought to be his fantastic memoir, I Never Had It Made, published in 1972 just days after his sudden death at age 53. In it, Robinson details the extraordinary challenges he faced as an agent of integration. And it offers equally keen insights into the man himself, particularly his life after baseball as he tried to balance family, business, and civil rights activism on his own terms.

Relying heavily on the letters of Robinson’s wife, Rachel, Arnold Rampersad’s 1997 Jackie Robinson: A Biography offers more nuanced details on Robinson’s upbringing in Southern California and his often-strained family life. The year before Robinson’s death, his son Jackie Robinson Jr. died in a car accident after struggling for years to overcome substance abuse issues related to war wounds suffered in Vietnam in 1965. Rampersad’s account of Robinson’s life is also a work of genuine literary merit crafted by one of the best biographers of the late-20th century.

Several excellent children’s books, too, have been written about the pioneering baseball star. Most impressively, Frank J. Berrios and Betsy Bauer’s My Little Golden Book about Jackie Robinson explains Robinson’s significance in an understandable and age-appropriate manner for young readers.

More recently, Kostya Kennedy’s True: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson (2022) delves into the transformative impact of four years in Robinson’s life, both as a player and in retirement. Kennedy’s book, more clearly than any other, makes evident the degree to which Robinson’s life was under a microscope from the moment he integrated minor league baseball in Montreal in 1946 (the year before he broke MLB’s color line with the Dodgers) until days before his 1972 death when he threw out the first pitch at a World Series game.

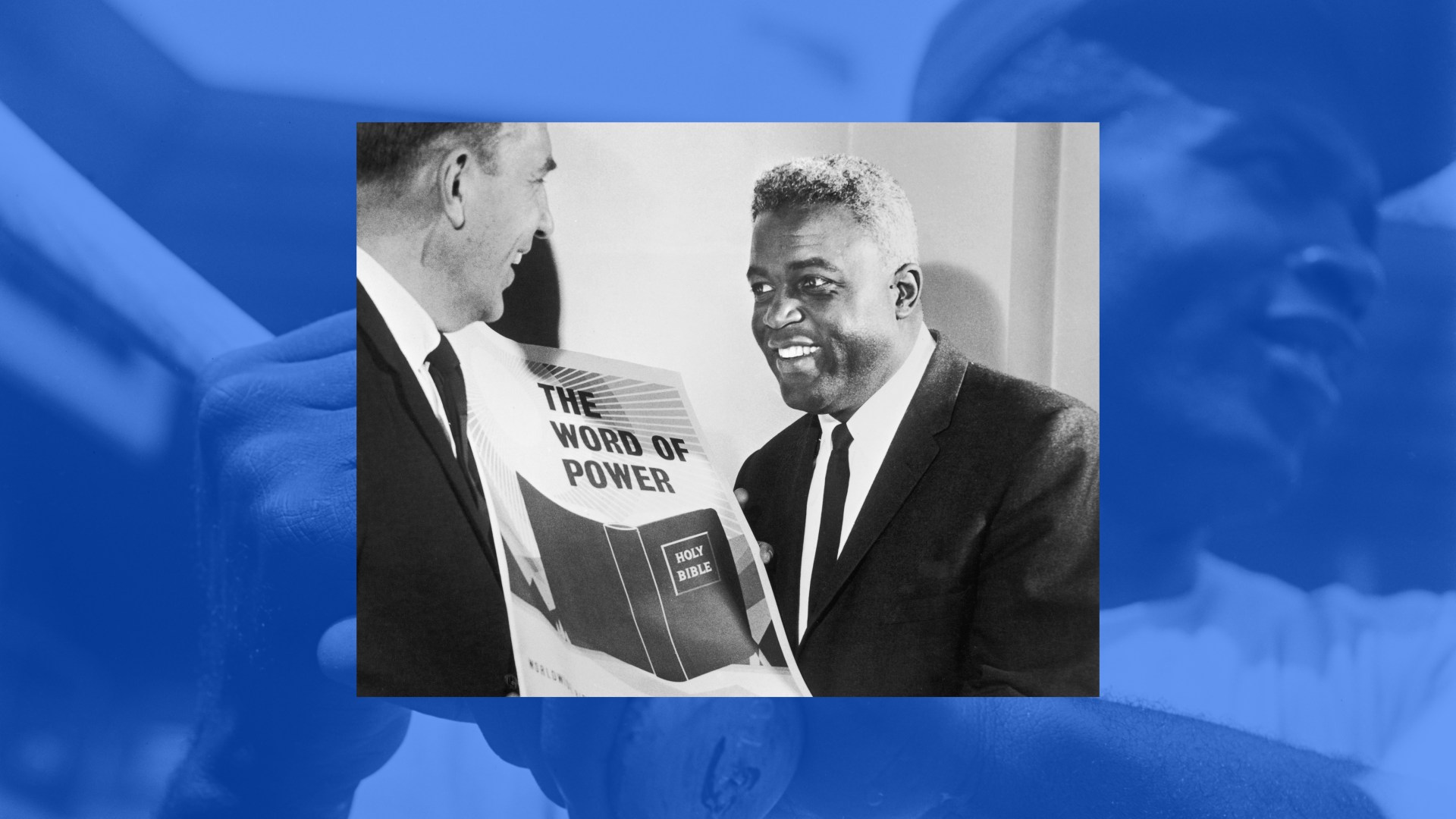

Ed Henry’s excellent 42 Faith (2017) opened the door to exploration of Robinson’s spiritual life and how it shaped his choices as both a public and private figure. Released at roughly the same time, Michael Long and Chris Lamb’s Jackie Robinson: A Spiritual Biography (2017) grounds its rendering of Robinson’s faith in the child rearing of his deeply pious mother, Mallie McGriff Robinson.

Straight and narrow

Historian Gary Scott Smith has built onto the wing of the Jackie Robinson library that Henry, Long, and Lamb started to erect a few short years ago. In Strength for the Fight, part of Eerdmans’s Library of Religious Biography series, Smith offers a more intimate account of Robinson’s spiritual life than was previously known. Rooted in previous books on his subject, Smith’s book is both a work of synthesis and a triumph of original research that casts a distinct analytical eye on Robinson’s religious life.

While Robinson hardly hid his faith under a bushel basket, he shared his views publicly in a more restrained fashion than many charismatic Christian athletes have in recent decades. Smith illustrates this sensibility by calling upon his subject’s frequent and typically sedate speeches to congregations and church groups, reflecting his mainline Protestant roots in the Methodist church. Robinson spoke calmly about the viciousness he often faced as baseball’s first modern African American player, frequently comparing his experiences to those of Job. Many African Americans who heard Robinson speak could relate to such indignities as they went about their own everyday lives.

Smith places Robinson’s Christianity firmly within the ecumenical sensibilities of 1950s and 1960s mainline Protestantism. In this cultural space, a consensus developed around the need for what Smith terms “social amelioration.” Robinson exemplified the spirit of the time, showing great comfort in both Black and white churches. The straight and narrow of the Christian life was Robinson’s haven in an often-heartless world.

It was also a pathway to social progress and to breaking down seemingly impassible barriers, as Robinson demonstrated time and again during his public life. He desegregated not only Major League diamonds but also housing and public accommodations in many of the cities to which he traveled. He desegregated corporate boardrooms as an executive for Chock full o’Nuts coffee. Such boundary-crossing appeal made him an attractive target for both Republicans and Democrats, who vied for his political allegiances.

For Robinson, politics were personal and rooted in his spirituality. As Smith shows, Robinson’s political and religious thinking was shaped in no small way by Karl Downs, his pastor at Scott United Methodist Church in Pasadena. Downs was just seven years older than Robinson, and the pair developed something of a big brother–little brother relationship. Downs had been schooled in a social gospel-infused theology at Atlanta’s Gammon Theological Seminary. He believed the church had a duty to redeem the wayward institutions of the world, a duty Robinson came to recognize as an essential part of the Christian life. But they believed such reform needed to be pursued within the constraints of basic Christian decency.

From an early age, Robinson was one to turn the other cheek, even while enduring discrimination in his hometown of Pasadena, feeling like an outsider on the predominately white University of California, Los Angeles campus, and facing all manner of enmity and exclusion as he traveled the country as a professional baseball player. Upon retiring after the 1956 season, Robinson became more active in politics, favoring the art of persuasion in the social gospel tradition over direct or militant action. He served as president of the United Church Men, an organization of roughly 10 million Protestant and Orthodox Christian men founded by the National Council of Churches, which threw its spiritually informed weight behind the civil rights movement.

Politically independent

Though formally a Republican, Robinson displayed a decided political independence when it came to issues of civil rights and Black empowerment. Residing in New York State, Robinson stood shoulder to shoulder with Republican leaders like John Lindsay and Jacob Javits, whose bona fides as advocates for racial equality were evident. The former Brooklyn Dodger gave staunch support to the presidential aspirations of Nelson Rockefeller, New York’s liberal Republican governor. He was disappointed when his party nominated Barry Goldwater, who opposed federal civil rights legislation, in 1964—and again in 1968, when he perceived Richard Nixon shifting away from support for civil rights. As a result, he openly supported Democratic presidential candidates: incumbent president Lyndon Johnson in 1964 and Hubert Humphrey in 1968.

While Strength for the Fight is a consistently interesting and informative read, its strongest sections are the ones focused on Robinson’s life after baseball. Robinson’s prowess as a mover and a shaker is evident, as are the subtle ways he infused his religious sensibilities into his efforts at social reform. To some extent, Strength for the Fight seems like old wine in new vessels, but the familiar turf on which it treads has yet to be covered with the distinct analytical eye that Smith brings to Robinson’s life and faith.

Clayton Trutor teaches history at Norwich University in Vermont. He is the author of Loserville: How Professional Sports Remade Atlanta—and How Atlanta Remade Professional Sports and the forthcoming Boston Ball: Jim Calhoun, Rick Pitino, Gary Williams, and College Basketball’s Forgotten Cradle of Coaches.