Last year I came across stinging words of rebuke against the ministry of Beth Moore. Her preaching and teaching was a “gateway drug to radical feminism,” said a young conservative. I found the rhetoric appalling, but I couldn’t tell that to the author of those words because he no longer exists. He was Russell Moore, circa 2004.

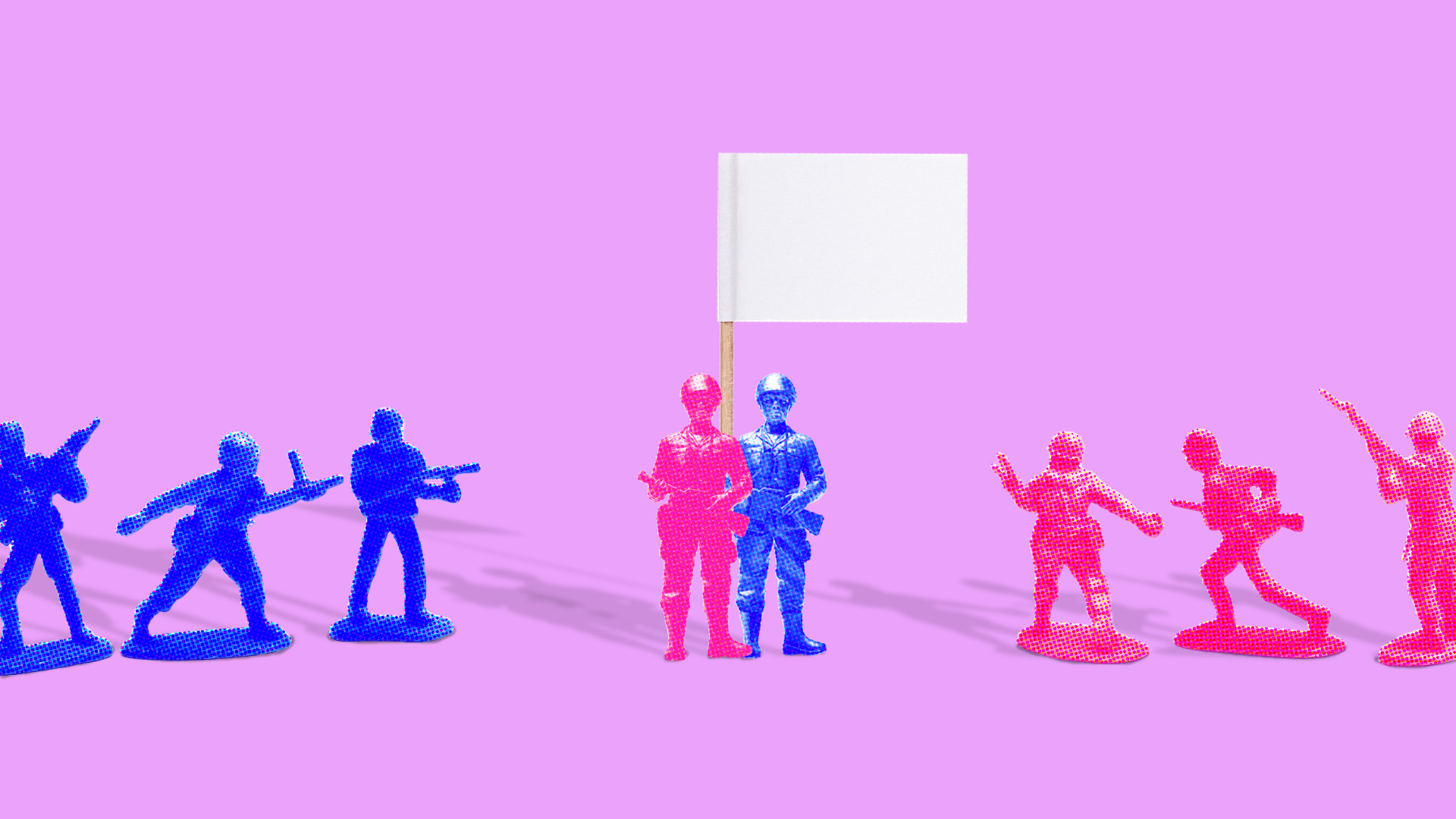

I was wrong about Beth Moore, but I’m even more chastened by the phrase gateway drug. The gender debate between complementarians and egalitarians was often fraught because it was a debate about just that: which views were “gateway drugs” to what abyss, which “slippery slopes” led to what error.

Some were convinced that egalitarians would lead us away from what the Bible declares to be good: that God designed us as male and female, that we need both mothers and fathers, that sexual expression is limited to the union of husband and wife. Meanwhile, others warned that complementarian arguments wrongly used Scripture the way an earlier generation did to defend white supremacy and slavery.

In recent years, many of us have seen old coalitions and old certainties torn apart. We’ve also discovered “slippery slopes” in unpredictable places. For those who are more traditional, the frustration started with an ever-narrowing definition of complementarian, measured increasingly by countering one’s “enemies” rather than by finding actual biblical consensus. First-order issues that define the catholicity of the church were treated as in-house debates while secondary or tertiary matters of “gender roles” were treated as matters of conciliar-like boundary-definition.

More importantly, recent scandals have demonstrated that the slippery-slope arguments of egalitarians were at least partially right—by pointing out that, for some, what lay behind a zeal for “male headship” was not responsibility before God but a psychologically stunted loathing of women or, worse, a cover for the sadistic silencing of women and girls. We see this not only in the uncovered horrors themselves but also in those who give no evidence of meeting the 1 Timothy 2 requirements for ministry—who, rather than putting away “anger” and “disputing” (v. 8), are the most eager to apply the rest of the chapter to castigate women leaders who’d dare to be a church’s guest speaker on Mother’s Day.

Whatever one might think of the “servant leadership” rhetoric of Promise Keepers a generation ago, we should agree that it’s quite a fall from that to today’s “theobro” vision of opposing such allegedly feminizing attributes as empathy and kindness. Turns out, there really was more John Wayne than Jesus, more Joe Rogan than the apostle Paul, in a lot of what’s been said to be “biblical.”

Many evangelical egalitarians have found themselves “homeless” too. They’ve been labeled in progressive circles as not “real feminists” precisely because, for them, the issue is how best to interpret inspired, authoritative Scripture—including Paul’s letters—not to deconstruct it. Today, when there really is a slippery slope of gender ideology that challenges the male-female binary, evangelical egalitarians spend more of their time in the outside world defending the idea that there is a complementarity of male and female, just not of the patriarchal sort.

As one woman minister told me, “I can’t go to the conferences I want to attend—with people I agree with on 99 percent of everything—because they think I’m ‘liberal,’ while some of the people who would celebrate that I’m ordained are horrified that I will never give up the essential biblical language of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.”

Many of us are rethinking who we once classified as “enemy” and as “ally.” Maybe the lines of division were in the wrong places all along. Those who hold to believer’s baptism, for example, have more in common with evangelicals who practice infant baptism than with Latter-day Saints who immerse adults. Those who disagree on how Galatians 3:28 fits with Ephesians 5 but who want to see men and women fully engaged in the Great Commission have more in common with each other than with those who would make gender either everything or nothing.

A new generation of Christian men and women is coming. When it comes to teaching them how to stand together, and how to equip one another to teach and lead, I trust Beth Moore much more than 2004 Russell Moore to show them the way.

Russell Moore is editor in chief of CT.