A Methodist woman in Albany, New York, didn’t want to go hear Zilpha Elaw preach. For one thing, Elaw was a woman, and that seemed “unbecoming.” To make matters worse, Elaw was Black, and that violated a sense of propriety and decorum. She didn’t want to go. But her husband persuaded her, and when she heard Elaw preach, she was convicted by the power of the Holy Spirit.

As Elaw recorded in her memoirs, the woman experienced a “quickening,” and “the word was effectually sown in her heart.” She experienced a kind of illumination and was able to read the Scriptures in a way she never had before. For Elaw, that was critical evidence of the work of the Spirit. “The Scriptures become as a new volume,” she wrote, and “develop new and surprising truths to the regenerate soul.” It is almost as if the person reading the Bible is reading alongside God—reading with the Spirit.

As I have read and studied the theology of Black women preachers in the 19th century, I’ve been struck by their pneumatology, their understanding of how the Holy Spirit breathes and blows in the lives of believers. Again and again, women like Elaw bore witness to the withness of the Spirit.

The term withness is not one that 19th-century Black women pastors would use. Yet this idea is demonstrated in their theology and in their lives and ministries. Alfred North Whitehead, a mathematician writing in the 1920s, used the word withness to speak of the body as the source and beginning of knowledge. Relying on the philosophies of David Hume and Rene Descartes, he was trying to interrogate our common understandings of how we know what we know. He argued we know things not just with our minds but with our entire bodies.

But the term can also be applied helpfully to the work and ministry of the Holy Spirit. The power, presence, and promise of the Holy Spirit means that the Spirit is always with us. The Holy Spirit is never far off but is in the world, actively working to reconcile us to one another through Jesus Christ. In John 14:16–17, Jesus promises to send the Spirit as an advocate to live with and guide the disciples. The Scripture also says the Holy Spirit helps Christians bear witness to the trials we face and God’s presence in them. In Romans 8:26, Paul says “the Spirit helps us in our weakness, for we do not know how to pray as we ought, but that very Spirit intercedes with groanings too deep for words” (NRSVUE).

Nineteenth-century Black women preachers in the United States exemplified and testified to the Spirit’s withnessing in their own lives. Facing the perils of racism, sexism, and even potential enslavement, their preaching testified both to a God who knew their suffering intimately and still called them blessed and to the Holy Spirit’s withness.

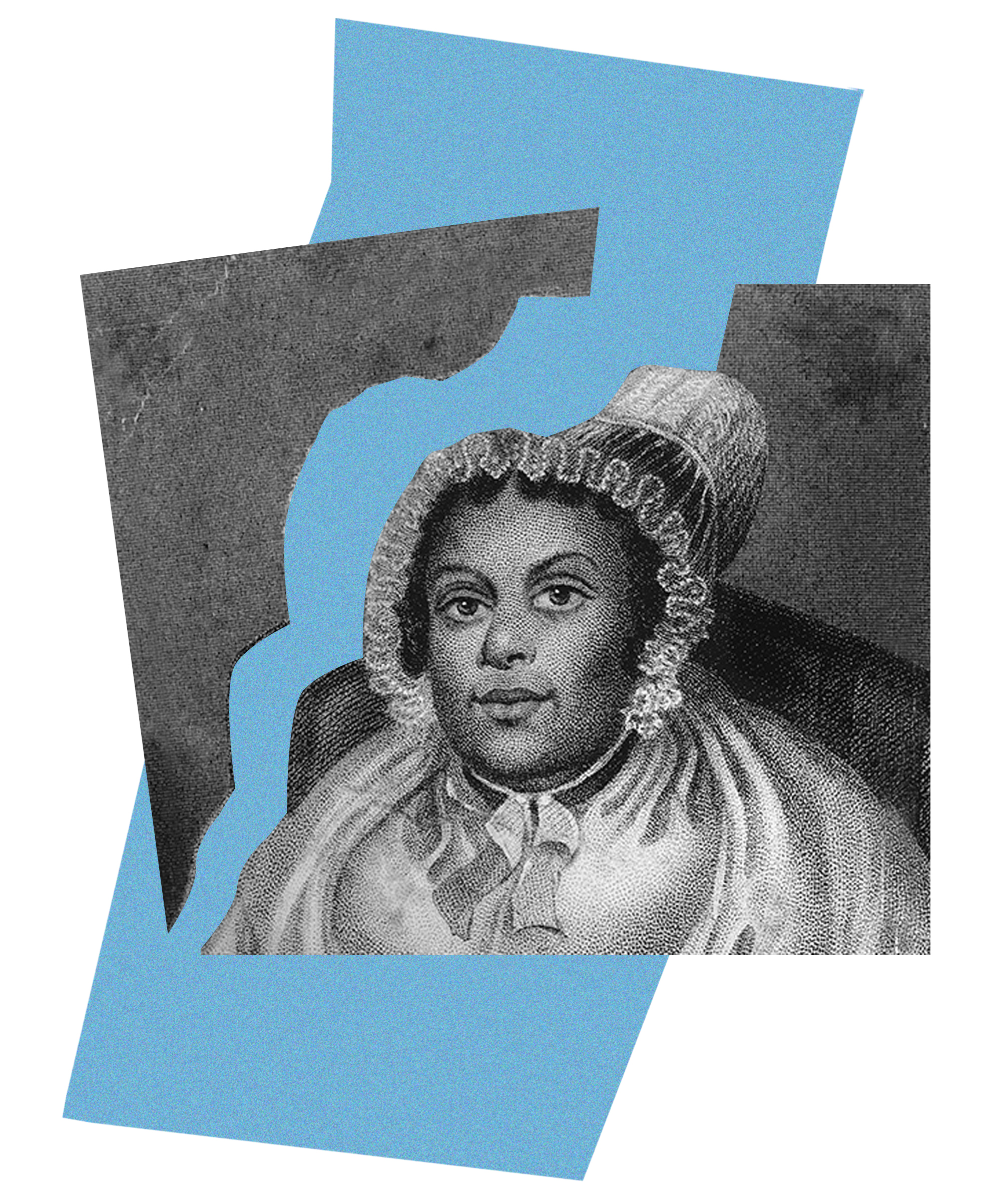

WikiMedia Commons / Edits by CT

WikiMedia Commons / Edits by CTFor Zilpha Elaw, the Spirit’s withness enabled her to preach against all odds, making space for her in a world that denied her humanity. Born in Pennsylvania in 1790, she was an itinerant Methodist minister, preaching as far north as rural Maine, where there were no Black people for miles, and as far south as Virginia, where she ran the real risk of being enslaved. When the Spirit led her to preach in England, British Methodist churches mentioned the presence of “The Black Woman,” not even noting her name. Nonetheless, she preached widely, drawing crowds.

Sometimes, her words were even able to convict the hearts of those who did not see her as fully human. Once in Alexandria, Virginia, for example, she preached to a crowd of enslavers. They thought it “strange” that a Black woman could teach the “enlightened proprietors the knowledge of God”—and even stranger that “in the spirit and power of Christ,” she “drew the portraits of their characters, made manifest the secrets of their hearts, and told them all things that ever they did.”

One historian points out this particular turn of phrase—“all things that ever they did”—is a reference to John 4:29, where when Jesus encounters the Samaritan woman at the well, she comes to believe in him and testifies to her neighbors. In the King James Version, the woman says, “Come, see a man, which told me all things that ever I did: is not this the Christ?”

The Holy Spirit within Elaw enabled her to speak hard truths to people considered educated and wealthy—people who had no doubt heard many more-refined sermons from people who gone to seminary and earned respectability along with their degrees. Yet she was able to preach with a power that convicted, by the withness of the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit inspired Elaw, even in her precarity and vulnerability, to proclaim the gospel to powerful white men who enslaved and brutalized people who looked like her.

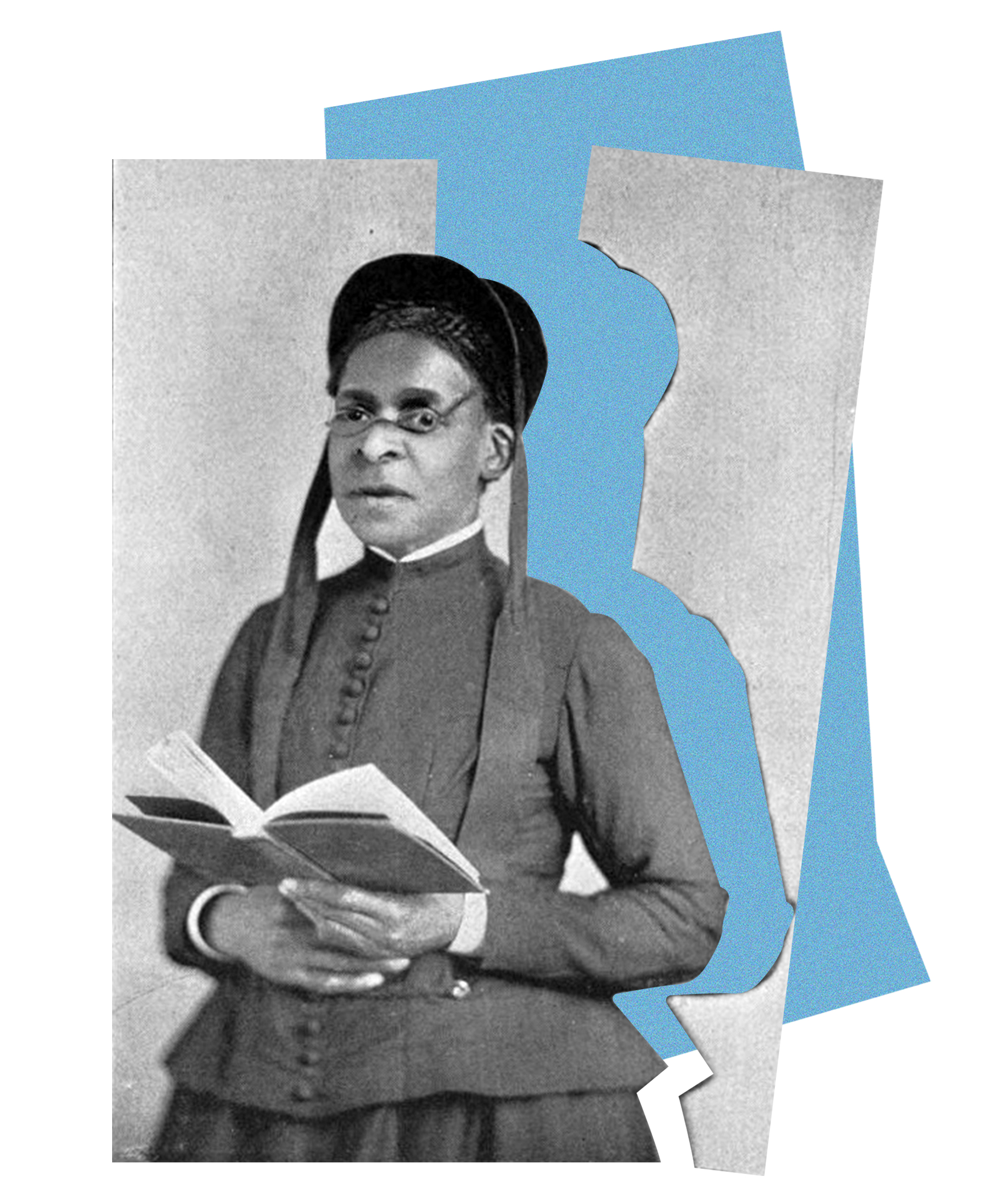

The Spirit’s withness catapulted another woman into itinerant ministry in the years before the Civil War. Julia Foote did not originally believe women could be called to preach. As she wrote in her autobiography, published in 1879, she had “always been opposed to the preaching of women, and had spoken against it” until she had a mystical vision of the Trinity. In the vision, God the Father asked her if she would go wherever she was sent, Jesus washed her and gave her a new robe, and the Holy Spirit gave her fruit to eat. God told her she had everything she needed to preach the gospel. After that, she began to actively evangelize. She became one of the first female elders in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and practiced a biblical exegesis that insisted on her humanity and the humanity of the people to whom she ministered.

Unlike Elaw, Foote didn’t preach to white people very often. At one white church where she was invited to preach early in her ministry, the congregation was segregated by race, and she refused to speak. The Holy Spirit would not accept such barriers and neither would she. The gospel was free for everyone. When she did find a place to preach, she noted the church was overfilled with people desperate to hear the good news.

WikiMedia Commons / Edits by CT

WikiMedia Commons / Edits by CTIn another case, Foote was traveling by boat overnight and went to sleep in the ladies’ cabin. A white man came in and, seeing Foote, threw a temper tantrum. He demanded she get up and leave because, as a Black woman, she was not considered a lady. Foote pretended to sleep as he ranted and raved, drawing the attention of the captain, who also implored Foote to rise. She decided, though, as she later wrote, that she thought “it best not to leave the bed except by force.” Both men eventually gave up bothering her, and she remained in her bed the rest of the night.

The Holy Spirit’s withness gave her strength to stay put so she did not acquiesce to the demands of white supremacy. For her, the Holy Spirit’s withness taught her and empowered her to say no to the ways “of the world.”

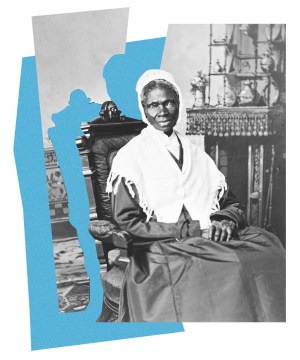

Sojourner Truth’s understanding of the Spirit as withness came from her childhood. Born Isabella Baumfree sometime around 1797, she was raised enslaved on a small farm in Dutch-speaking New York. Her first spiritual experiences came through her mother, known affectionately as “Mau Mau Bett.” Her mother taught her “there is a God, who hears and sees you” and she should “go to God in all her trials, and every affliction.” Truth understood from an early age that God was with her, even as she was beaten.

Empowered by this knowledge, before New York required manumission, she walked from her bondage with her infant daughter.

She found fellowship with several faith communities along the way and eventually ended up in New York City. Here, in midlife, as she served impoverished urban communities, she felt God’s call to preach and lecture. She knew her family and friends would be hesitant about it, so she kept it a secret as she packed only what she could carry in a pillowcase. When she departed, she announced her name was no longer Isabella but Sojourner and explained that “The Spirit calls me … and I must go.”

Truth understood the witness of God, guiding her. The Spirit led her to bear testimony to the cruelty of enslavement, fight for women’s suffrage, speak with Abraham Lincoln, tend to the wounded in the Civil War, and preach to a crowd of 1,200. The Spirit’s withness showed her that every person was a child of God and that God cared about the whole self—body, mind, and soul.

WikiMedia Commons / Edits by CT

WikiMedia Commons / Edits by CTWe know, of course, that God’s character does not change. But the Spirit moves, and by that power, people change. It is common today to view change as a sign of weakness, but in the preaching of Black women in the 19th century, change was a testament to God’s strength and the transformation wrought by the Spirit’s withness.

Truth, Foote, and Elaw all saw how the prophetic and the pastoral are deeply connected, as the Spirit simultaneously calls out sin, changes hearts, comforts the repentant, and opens “regenerate souls” to “new and surprising truths” about the Good News of God’s reconciliation. Many, I think, respond at first like that woman outside Albany who thought Elaw’s preaching would be unbecoming. But like her, we too can be quickened by the Spirit and experience that divine withness if we will listen to the teaching and testimony of these Black women preachers from American history.

Kate Hanch is a pastor at First St. Charles United Methodist Church in Missouri. She has an MDiv from Central Baptist Theological Seminary and a doctorate from Garret-Evangelical Theological Seminary. She is the author of Storied Witness: The Theology of Black Women Preachers in 19th-Century America.