I was in elementary school when I learned the words to all three verses of “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

As a Black adolescent in the Leimert Park neighborhood of Los Angeles—made famous by movies such as Boyz n the Hood, Training Day, and Straight Outta Compton—this song had particular meaning to me. It was sung with pride at church and social events during Black History Month, an annual commemoration that Black lives, Black accomplishments, and Black achievements matter.

Now known as the “Black national anthem,” “Lift Every Voice and Sing” was penned in 1900 as a hymn of hope—grounded in the belief that resilient faith would sustain us against oppression.

James Weldon Johnson, the songwriter, was born in Jacksonville in 1871 to a Haitian mother from the Bahamas and a father from Richmond. The Johnsons had moved to the coastal Florida city, which stood out as a place in the South where Black people had access to education (though segregated) and economic opportunity.

Like many other Black Americans at the time, James Weldon Johnson was influenced by the message of educator, orator, and public intellectual Booker T. Washington. Born into slavery in 1856, Washington advocated for Black liberation through economic and educational achievement, serving for decades as the first leader of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (now Tuskegee University).

Washington was also a devout Christian who integrated his pragmatic approach to faith into his service as an educator and national leader. He believed that God was powerful enough to liberate Black people from the evil of racism. Washington’s focus on education and emphasis on hope and resilience inspired Johnson.

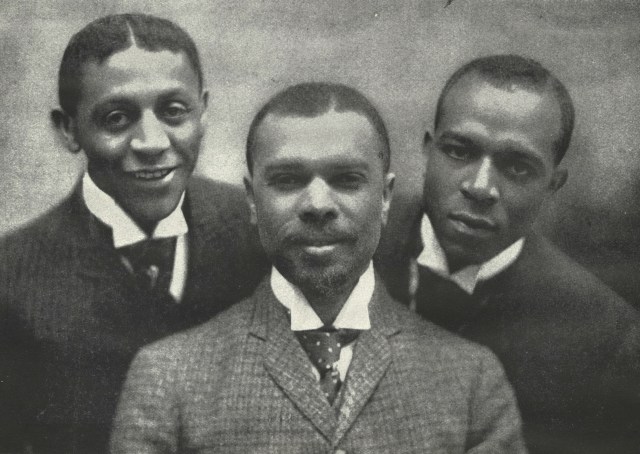

New York Public Library / Wikimedia Commons

New York Public Library / Wikimedia CommonsAfter attending Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University), Johnson returned home to serve as principal of his middle school alma mater. For a celebration of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday in 1900, the young educator penned “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” which 500 middle schoolers sang in tribute to Booker T. Washington. Johnson’s prose was set to music by his younger brother, J. Rosamond Johnson, a New England Conservatory–trained composer.

Both at church and at home, James Weldon Johnson developed the foundational theological and practical faith that came through in his three-stanza hymn. With lines such as “Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us / Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us,” the song evokes the struggle of Black Americans, our sights on victory, and our prayer that God would continue to lead us.

Johnson grew up in Jacksonville’s only Colored Methodist Episcopal (now Christian Methodist Episcopal) church, believing that through education and faith Black people could achieve. Local Black churches, predominately Methodist and Baptist, were the most influential entity uplifting and preparing Blacks for the oppressive forces of post-Reconstruction racism.

The churches supported and, in some cases, created educational institutions; economic development and volunteer organizations to provide mutual aid; cultural gatherings; and, in the case of the Afro-American Life Insurance Company, insurance policies. Ebenezer Methodist Episcopal Church, where the Johnsons attended, was one of the largest congregations and one of the most actively engaged, with a focus on self-determination, self-awareness, and pride.

At the time of the writing of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” Jacksonville had been a haven for snowbirds. Tourism, however, was disrupted by the Spanish-American War, horrible yellow fever and typhoid outbreaks, and the resulting deaths. White-supremacist ideologies permeated the southern city through Jim and Jane Crow written and unwritten laws. Although there was a small Black middle class of ministers, teachers, and small-business owners (like barbers, tailors, cobblers, and grocers), Black people as a whole were not thriving socially, economically, and certainly not politically.

“Lift Every Voice and Sing” is a faith-oriented, inclusive, and pragmatic response to the societal ills Johnson saw around him. Faced with white supremacy, nationalism, and the proliferation of colonialism, he put to words a theology sung out from the mouths of children, a calling to “lift every voice and sing” and “march on ’til victory is won.”

The melody is as complex as the lyric. The Johnson brothers were intentional about not sugarcoating the urgency or the seriousness of preparing young people for the days ahead. The difficulty of tune and text made it worthy of committing to memory and thus internalizing the message and the vision of hope.

The first verse of the hymn points to a redemptive arc toward “the harmonies of Liberty.” Johnson’s second verse is a lament that acknowledges the vestiges of our nation’s oppressive, “gloomy past.” These lyrics come not as a doldrum of depression but as a way to avail meaning to the resilient hope that is cast as the vision forward in the first verse.

The final verse is a prayer that positions the second verse as a launching point for achieving the aspiration of the first—with divine assistance, of course. “God of our weary years, God of our silent tears,” the song goes, “Thou who hast brought us thus far on the way …” Although Johnson had great proximity to hymnody, his affinity to poetry, especially that of Rudyard Kipling, inspired the shape of “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” Kipling’s “Recessional” offers a glimpse at a possible literary influence.

Johnson’s prose was intentional—to show middle schoolers, who even as kids faced the horror of Black oppression, that this was their experience and their truth. Their preparation for a future lay in interacting with a vision of Liberty’s harmonies through a theological lens that victory can be won if we stay “true to our God” and “true to our native land.”

Johnson later wrote that the song spread as those students kept singing it and teaching it to others, and “within twenty years it was being sung over the South and in some other parts of the country.”

Like the young middle schoolers of Johnson’s school, my peers and I faced challenges during our youthful days. Ours were different yet still traumatic. Although many of us were taught poems by Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Maya Angelou, we found more applicable inspiration in songs of Motown, Philadelphia International Records, and Stax. Each year, our favorite recording artists would appear on television singing “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” making our ability to sing it too, more potent, more palatable, and, simply put, more personal.

We navigated the streets of Los Angeles more fearful of the corrupt civil servants than gangbangers and more anxious about nefarious stereotypes than the drug-infested streets. As young citizens too young to vote, we believed in having the courage to “sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us,” and we believed that “we have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered.”

Beyond an anthem or a song of faith, this is a hymn of hope and invitation. It gives us hope for an inclusive, equitable, and just society and an invitation to be a part of the making of such! Let us all commit to “lift every voice and sing, ’til earth and heaven ring, ring with the harmonies of Liberty!”

Emmett G. Price III is the inaugural dean of Africana studies at Berklee College of Music & Boston Conservatory at Berklee. He also serves as president/CEO of the Black Christian Experience Resource Center (BCERC) and can be reached via emmettprice.com.