In this series

Bahala na.

Itu sudah takdir.

Nanigoto mo akirame ga kanjin.

These are some of the popular phrases that people in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Japan use when faced with circumstances they feel resigned to. They’re akin to another common quip: Que sera sera, derived from the Italian for “Whatever will be, will be.”

In other words, these expressions often carry a fatalistic attitude toward life. Fatalism refers to the belief that events that occur are fixed in advance, such that human beings are powerless to change them. While fatalism’s impact and influence may not be overtly discernible, it permeates aspects of culture, whether because of a particular country’s religious roots or its historical and political developments.

This may be especially so in Asia, which is considered one of the most religiously diverse continents in the world. Singapore, Taiwan, Vietnam, South Korea, China, and Hong Kong constitute 6 of the 12 societies worldwide with a “very high degree” of religious diversity, according to the Pew Research Center.

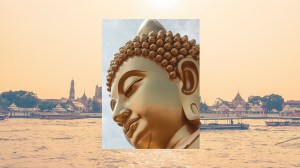

In countries like Thailand, Sri Lanka, and India, a Buddhist or Hindu worldview contributes to the idea of karma, where one’s actions in the present will determine the outcome of one’s future life. In Indonesia, it is Islam that shapes fatalistic thinking (captured by the common phrase “inshallah”). In South Korea, Korean shamanism is a contributing factor toward the widely accepted practice of fortunetelling. In Hong Kong, astrology, luck, and feng shui play a large role in crafting one’s understanding of destiny or fate.

But fatalism isn’t just restricted to cultural and social spaces. It also impacts the ecclesiology and missionality of churches in Asia, which can be gleaned in responses to suffering, natural disasters, or political instability.

Christianity Today interviewed the following pastors and scholars in South, Southeast, and East Asia on how fatalistic thinking shows up in their cultures, what the key sources of fatalism are in their contexts, how fatalism has impacted or influenced their churches, and which Bible verses challenge it. Their responses can be found in this special series’ eight articles, listed to the right on desktop and below on mobile:

Hong Kong KK Ip, senior pastor of EFCC-International Church in Wan Chai

Indonesia Amos Winarto Oei, lecturer in ethics, dogmatics, and history at Sekolah Tinggi Teologi Aletheia in Lawang

India Havilah Dharamraj, head of biblical studies at the South Asia Institute of Advanced Christian Studies in Bengaluru

Japan Kei Hiramatsu, pastor and New Testament professor at Central Bible College in Tokyo

The Philippines Dick O. Eugenio, dean of the School of Leadership and Advanced Studies at Wesleyan University–Philippines in Cabanatuan City

South Korea Paul J. Park, assistant professor of systematic theology at Torch Trinity Graduate University in Seoul

Sri Lanka A. N. Lal Senanayake, president of Lanka Bible College and Seminary in Kandy

Thailand Kelly Hilderbrand, director of DMin program at Bangkok Bible Seminary in Bangkok