Faith and church have been tough for a lot of people coming out of the pandemic. I’m one of them. The last three years ushered my wife and me through two job changes, a cross-country move, and months spent hunkered inside, trying to keep our young children healthy and ourselves sane. By the time the world began to reopen, so much felt different.

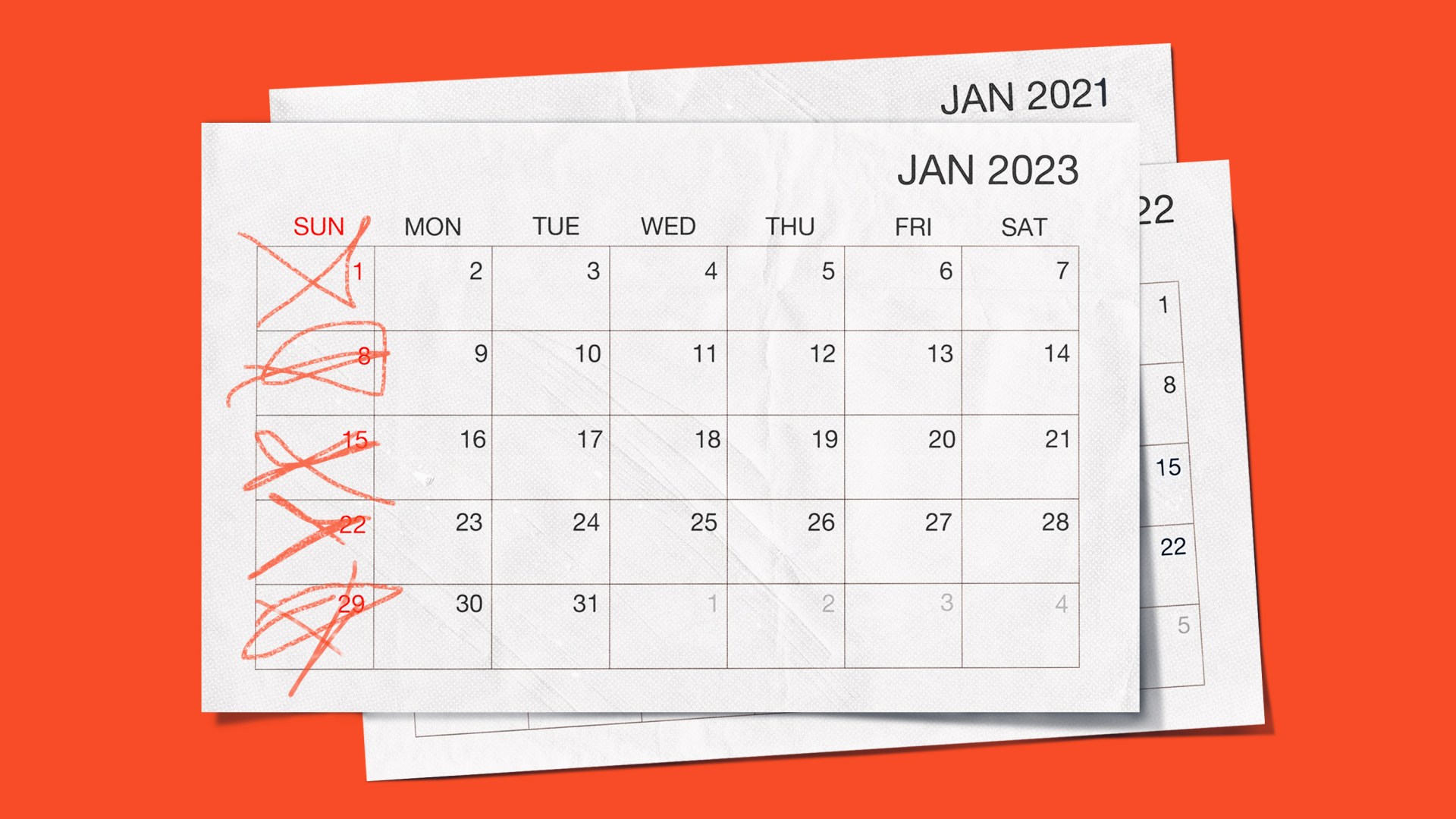

Until recently, I could count on one hand the number of times I’d physically attended a church service since March 2020. I could give many reasons for our absence—a toddler and a newborn, disillusionment with a church tradition that was once home, enjoying a second weekend morning, sheer exhaustion, and more.

But if I’m really honest, one reason stands out: The further I get from church, the less Christian faith makes sense to me. The physical drift begets an intellectual one.

Although I might sound like a Christian upstart, I’m something of a thoroughbred. I was born and raised in what is now an evangelical megachurch. I graduated with a degree in religion and philosophy from a prominent Christian college, and I finished a seminary degree at another. I got chops.

But when it comes to believing my faith, it’s always been the same. During any season of life when I’ve been separated from like-minded Christians, my faith starts to feel as alien to me as it does to my non-Christian friends. Wait, you believe a man was God? That he actually rose from the dead? Like, his blood and guts cooled and then his heart just started beating again? It’s ludicrous, isn’t it?

Part of my experience of faith—and part of my constitution—is that I’ve always sought out the best arguments against my own positions. And with Christianity, there are plenty of good critiques. Feuerbach, Nietzsche, and Freud all offer substantial ones, describing the Christian faith as variations of wishful thinking. Hypocrisy is another good reason for doubt. The church past and present is full of Christians failing to be faithful to its message.

Arguably the best reason to disbelieve is the problem of pain, or theodicy, as they say in thinky circles. If God is so great, why is there so much evil and suffering in the world?

One particular horror story landed hard with me last year, in the middle of my church absence: news of the passing of Jonathan Tjarks, a staff writer for The Ringer who primarily covered NBA basketball. He’d written powerfully about facing a cancer diagnosis a year after the arrival of his firstborn son. I never met Jon, but we corresponded briefly about writing, faith, and sports. Jon, too, was a Christian, and I, too, am a sports nut.

On the website chronicling his cancer journey, in the final entry before his passing, Jon’s wife includes a picture of Jon in a hospital bed, clearly exhausted, his big frame broken down, being helped to kiss his son Jackson. After the pandemic had weakened my formidable insulation from death, the photo’s caption—“Jon’s last kisses to Jackson”—wrecked me.

That night, I wept at the bedsides of my own sleeping sons, ages five and two, kissing their warm foreheads. I wept for Jon. I wept for Jackson. I wept for my sons, at the thought of my own fragility and theirs. Really, I wept for all of us.

In the piece he’d written before he passed, Jon had talked about the importance of living life intentionally beside others, not just with his family but also with his church. Friends had asked him if he’d been extra careful to isolate during the pandemic. His reply? He didn’t have time to.

Jon’s story compelled me. A few months after his passing, my wife and I agreed it was time to go church hunting. We wanted our boys to grow up in church. And at times, we felt a dull ache on Sunday mornings that donuts and coffee couldn’t alleviate.

The process was hard. Between a graduate degree in theology and my inclination to question everything, I was a bit of a liability. I have enough squirminess about church culture that I knew we’d need to visit a lot of them.

One benefit of the pandemic’s streaming revolution was the ability to peek into a service without dedicating a whole Sunday to each visit. Some mornings, my wife and I would “visit” three churches without leaving our couch or even putting down the donuts. When we saw a non-starter—like, say, a prayer addressed to Mother Earth, or a pastor leading the congregation in “America the Beautiful”—we could jump off the feed and try the next one.

By the time we found a small church near our house, we loaded up our boys and gave it a go. The first handful of people we met there were kind and welcoming, and neither of our boys hated the kids’ care. So we went back. And we kept going back, enough to catch ourselves saying “our church” in conversations with family and friends.

The church was located downtown and transparent about its dedication to local residents, especially those hurting in the community. The services were fairly short, the sermons sometimes moving and sometimes not, the music unoffensive. The microphone crackled every Sunday, and every Sunday people scrambled to figure out why. After years spent in churches where fog machines outnumbered homeless visitors, the simplicity of the church was a balm.

Our first visit was last December, and since then, our family has been adjusting to a new/old Sunday morning routine. It hasn’t always been fun to have our Sunday mornings spoken for. But being there has been good. Deeply good. And by the time Easter came this spring, we knew where we’d be, and we were actually looking forward to it.

Getting out the door for church with young children is dependably Kafka-esque, and by the time we found parking and made it inside, even the dusty chairs in the sanctuary were full. Helpful members unstacked the dustiest ones for us. The service looked and sounded normal, aside from the crowd and the unmistakable electric edge of Easter mornings. We celebrated Christ’s triumph over death, and Christianity’s stake in the ground of human history. “Foolishness to the Greeks,” the apostle Paul said.

As I stood there singing, I couldn’t help reflecting on my time away. I’d missed standing in that dim glow, awash in the chorus of voices. I’d missed the gravity of an Easter morning, the intimate force of communion, the Lion and the Lamb.

Wishful thinking, I still say on my less faithful days.

Paul once prayed that the Ephesians would comprehend the massive scope of Christ’s love. He added an extra line, though: “I pray that you, together with all the saints, would have power to grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ” (Eph. 3:18–19).

The strength of togetherness is one of the things I’ve noticed most about being back in church. These days, my faith feels less like a running tally of facts and more like a light switch. Being back together has reminded me that the light switch wasn’t always quite so heavy.

But I can’t help thinking of Jon and Jackson, either. As Jon wrestled through his diagnosis, at least in writing, he never came to some glorious peace about his departure. And to offer him (or anyone) glib answers in the face of that kind of suffering would be, to borrow from the author David Foster Wallace, “grotesque.” Jon still had to kiss his son goodbye, and that pain has a gravity all its own.

After my first Easter service back, I was still thinking of Jon and the passages of Scripture he kept coming back to as his odds got longer and his time shorter. Religion that God our Father accepts as pure and faultless is this: Learn to do right; seek justice. Defend the oppressed. Take up the cause of the fatherless; plead the case of the widow (James 1:27; Isa. 1:17).

Jon was thinking of his wife and son, of course. But if there’s one thing the past three pandemic years have taught us, it’s that we’re all in Jon’s predicament. All of our days are measured. We don’t get to decide how long we live. However, we do get to choose whether we spend those days with each other and for each other, even in our darkest seasons.

This, I’ve realized, is what I was looking for in a church: a community that takes James and Isaiah as seriously as it takes Paul’s writings about the Resurrection—a church whose care for the hurting can help me keep the light switch on when life feels so unbearably fleeting and mortal.

Luke Helm is a writer and coach working out of Grand Rapids, Michigan.