In July of 2007, Bible translators from a dozen Nigerian languages came together in the rural town of Bayara, Nigeria, for a three-week workshop to begin translating the Gospel of Luke. They gathered in a steel-roofed school building with a number of outside consultants—some Nigerian, others American and British.

At the end of Friday, July 27, they had wrapped up their first week of work and made plans to unwind. Multilingual collaboration is taxing, and everyone was eager to eat dinner and watch a movie.

The translators gathered their papers, books, and laptops into bags and slung them over their shoulders. One of them grabbed a USB thumb drive attached to a lanyard, which they used to pass files back and forth and store backups of their work.

They walked half a kilometer through the warm evening air to a guest house where they were staying near the local hospital. The cooler rainy season had just begun, but this day had been neither cool nor rainy.

The group finished eating around 7:30, and Veronica Gambo, the wife of one of the translation consultants, made popcorn. She filled a bowl and was carrying it out to join the others in front of the television when men with automatic rifles burst through a door into the kitchen.

Gambo froze. A man put a gun barrel between her shoulder blades and marched her, still bearing the popcorn, into the living room.

“Get down!” Danjuma Gambo, Veronica’s husband, remembers the men yelling. They fired shots into the walls and ceiling. They forced everybody to the ground, including the translation project’s leader, a silver-haired British woman in her late 60s.

Andy Kellogg, an American working as a Bible translation consultant, was lying on the floor and wondering: Would the men rob them and leave quickly, or do something worse?

“If you’re in a remote place, and it doesn’t seem like help will be coming quickly, you can take your time as a robber,” Kellogg said. “And we were in a remote place.”

Fortunately for the translators, the men were not religious terrorists. The brigands had come for the laptops. They took nine in all—and the translation work stored on the computers’ hard drives—along with personal belongings like passports and credit cards.

When the thieves left, the project leader, Katharine Barnwell, rose from the floor and dusted off her clothing. She checked with each translator to make sure they were okay. Then someone spotted something the thieves had overlooked hanging on a nail in the living room: the lanyard with the USB drive. The sole backup of their translation work.

Barnwell spoke in a matter-of-fact, British way: “Right. Well, we’re not going to let this stop us.”

Having worked in Nigeria most of her career as a linguist with the translation organization SIL, Barnwell had tallied her share of brushes with danger. Six times she was robbed at gunpoint. She’d survived multiple rounds of malaria. She had endured the constant threat of Boko Haram and terrorists who bomb churches.

Barnwell wanted to press forward with the project, and after some discussion, every worker decided to stay and continue the workshop. Within a few minutes, Danjuma Gambo said, the group burst into song, praising God and praying for a way to finish God’s work.

There was one difficulty: We have no computers, Kellogg thought. This is going to be really hard on Monday.

But on Monday, when they returned to work, they found that every laptop had been replaced. It was not the result of emails, funding requests, forms, or petitions to Western missions agencies. The computers were gifts from local Nigerian Christians.

News of the robbery had spread quickly, and “there were some influential people in churches nearby who donated,” Kellogg said. Local churches and benefactors wanted the translations to continue. They believed in the work and were driving it.

With the thumb-drive backup, Barnwell’s team quickly restored their work and picked up where they left off. They went on to finish the Gospel of Luke in each of the 12 Nigerian languages, quickly followed by 12 new translations of the Jesus film, whose script comes almost entirely from Luke. Many of those languages now have full New Testaments, according to Kellogg, and some have moved into translations of the Old Testament.

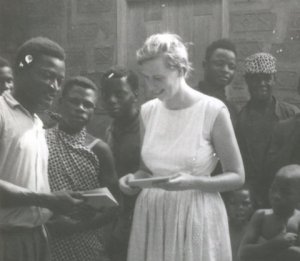

Photos Courtesy of Katharine Barnwell

Photos Courtesy of Katharine BarnwellThe incident in northeast Nigeria is a freeze-frame from the great missiological shift that has been playing out over the past 50 years: the transfer of ownership from Western individuals and institutions to leaders in the Global South. The idea that Americans and Europeans are no longer in the pilot’s seat of the missions enterprise—and are being rapidly replaced by Christians in the majority world—is no longer new. It is taken almost as a given for how the gospel will spread in the 21st century.

Nigerian ownership is what saved the projects born from Barnwell’s workshop—or at least what helped them quickly back to their feet. And it was perhaps poetic: Barnwell, a Westerner, was one of the earliest champions of empowering Nigerians to take over translation work in their country.

In fact, it’s likely that no living person has had a greater influence on the world of Bible translation than Barnwell, who is now 84. But unless you’ve worked in the industry—I was a Bible translator when I first met Barnwell at a Texas conference a decade ago—you’ve probably never heard of her.

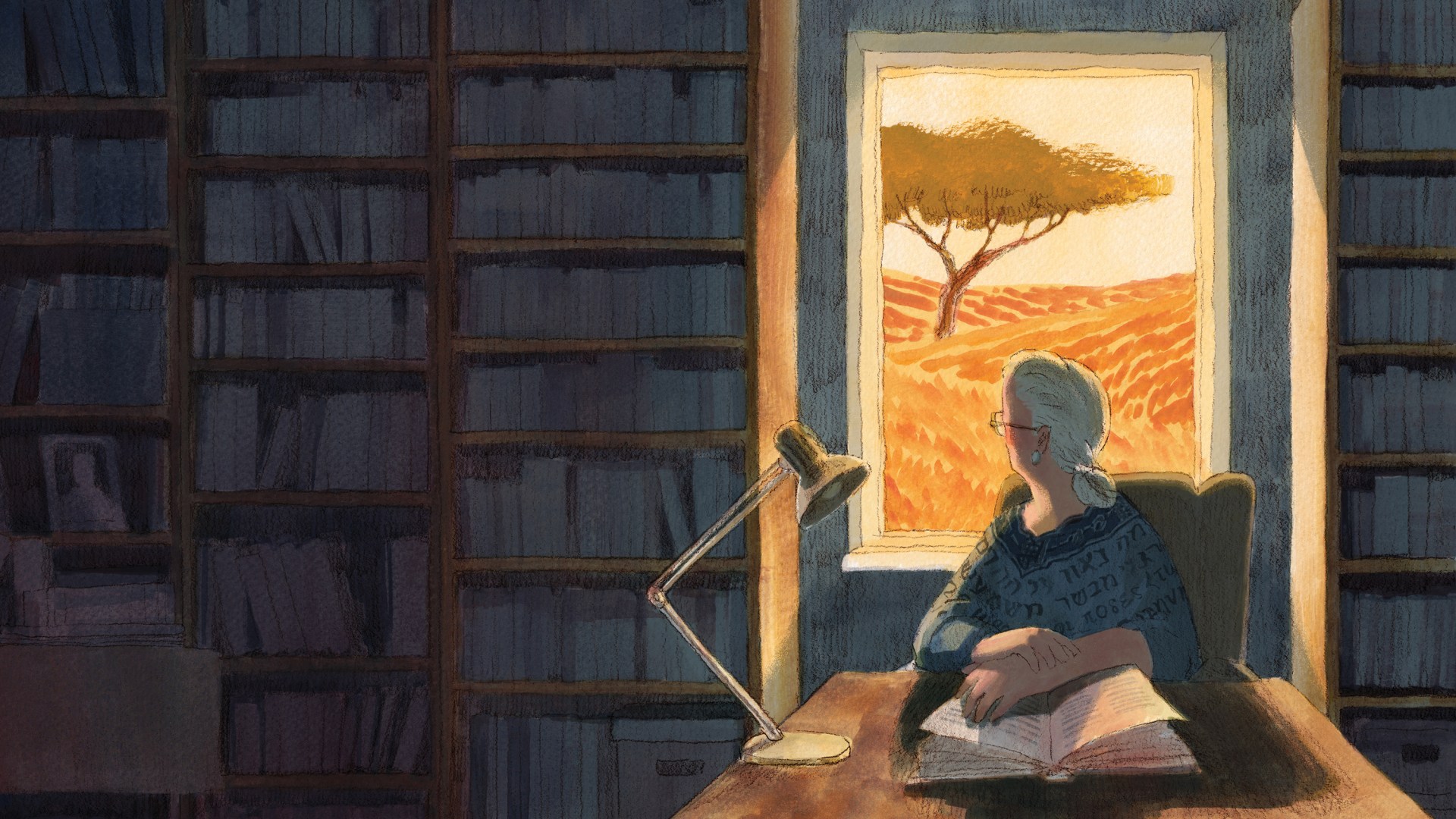

Katharine Barnwell was born in London in 1938. Her earliest memories take place underground, hiding from Nazi bombing raids. To escape the dangers of war, Barnwell and her siblings were sent away to live with family in the countryside, much in the way The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe opens.

As a child, and still today, Barnwell loved reading. In 1956, she enrolled in the English language and literature program at the University of St Andrews, one of the few British universities at the time with a large concentration of young women.

“I grew up in a churchgoing family, a very genuine churchgoing family. But it was only later,” Barnwell said, “through the ministry of the Christian Union when I got to university, that I came to understand what it really meant to follow the Lord.”

Around the time she was dabbling in linguistics in one of her courses, analyzing and diagramming the English language, Barnwell attended a meeting with George Cowan, then the president of Wycliffe Bible Translators International, who shared about the need for Bible translators.

“That was it for me,” Barnwell said. She began taking training courses with Wycliffe before she even graduated school.

In 1960, Barnwell began studying with the Summer Institute of Linguistics—known today simply as SIL—and was invited to return the following year to teach.

In her teaching, Barnwell focused on semantics. “It’s really the theory of meaning,” she explained. “When you’re translating, you’re not translating the words, you’re translating the meaning. So how do you translate the meaning, and how do you recognize the categories there are in meaning?”

When doing Bible translation, this distinction between language’s form and language’s meaning is not trivial. It’s at the very foundation of the discipline.

Barnwell’s early studies in semantics shaped the rest of her 60-year career. She spent much of those decades training others on the nuances of semantics and, critically, developing ways for people without a graduate-level education to understand it.

Almost inadvertently, she revolutionized the world of Bible translation.

Photograph by Michael Wharley for Christianity Today.

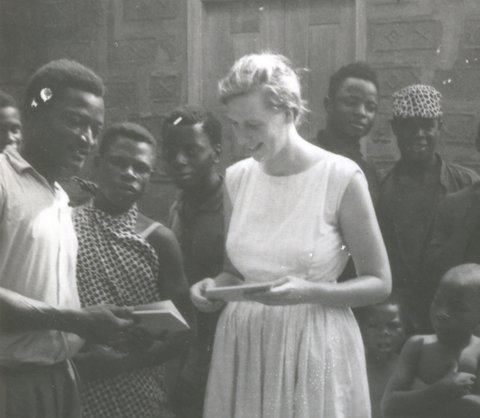

Photograph by Michael Wharley for Christianity Today.Barnwell moved to Nigeria in 1964. Newly independent from Britain and one of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world, Nigeria was a sort of promised land for translation. It has nearly 700 languages, and at the time, most of them did not have a word of Scripture. Many had never even been written down and lacked an orthography—a writing system fitting their sounds.

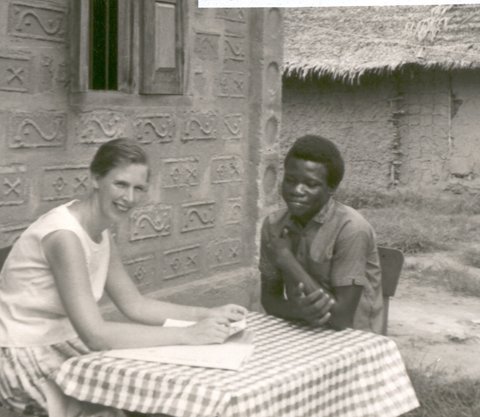

SIL sent Barnwell to the Mbembe, a people group scattered across villages in Nigeria’s southeast corner. She started from scratch.

“Happily, the people were very keen on me learning the language,” Barnwell said. She remembers a woman befriending her early on and teaching her new concepts. “The next day, she’d ask me again, and if I couldn’t remember, she’d say, ‘I told you that yesterday!’”

Barnwell said she quickly won the hearts of her Nigerian colleagues—referred to at the time as “language helpers”—and made a home there. (Today, she has spent more of her life in Nigeria than in the UK.) The future looked bright.

But in 1967, Nigeria exploded into civil war. What’s known as the Biafran War would claim well over a million lives through conflict and resulting agricultural catastrophe.

As Western missionaries left the country, Barnwell tried to remain. But the fighting drew so near that she and another single female missionary had to drop everything and escape. They fled first on foot, then up the Cross River via canoe to Cameroon, where authorities let them cross the border without documentation. From there the women flew to England and waited for it to be safe to return.

Barnwell made the most of her time in limbo. Equipped with her fluency in the Mbembe language and her field data, she completed her PhD at London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS).

In 1970, she returned to Nigeria and to her translation work—only to be uprooted again half a decade later when a political event some 400 miles away set the stage for a reordering of the Bible translation landscape.

On February 13, 1976, Lieutenant Colonel Buka Suka Dimka and a group of his followers attempted a coup d’état in Lagos, then the capital of Nigeria. Though the coup was carried out by Nigerians, it inflamed suspicions about outsiders among Nigeria’s military rulers who thwarted the overthrow.

“Politically,” Barnwell said, “some people felt they didn’t want to promote the minority languages. Division between the different language groups or tribes was a sensitive issue. That was the main reason—there were people in authority who didn’t want to see that [promotion] happen.”

Two weeks after the attempted coup, Nigerian immigration officers met with the Western leaders of SIL and ordered them to appear in Lagos on March 18. When they did, they were given two weeks to wrap up their research and transfer it to a Nigerian university. All SIL linguists were to leave the country.

It was a sudden and astonishing setback that threatened to end translation work in what was arguably Africa’s most important field.

Nigerians and expatriate missionaries hatched a plan to save their work. They quickly assembled a delegation of influential Nigerians—politicians, business leaders, even Festus Segun, the Anglican bishop of Lagos—and pled their case with the government in Lagos: Could the work continue if they transferred full ownership and leadership into Nigerian hands? The government granted the request. Thus began the Nigerian Bible Translation Trust (NBTT), today one of the leading Bible translation organizations in Africa.

Photos Courtesy of Katharine Barnwell

Photos Courtesy of Katharine BarnwellWith the agreement, the translation leaders averted disaster. But that was the easy ask. They had a second request: If they were to lose dozens of Western scholars, could they keep a mere four expatriate workers? They might need to stay 20 years to fully train and transfer the leadership of the organization.

This, they knew, would be much harder for the government to stomach.

In the 1970s, translation agencies were dogged by rumors that their missionaries were cooperating with the CIA and other US government agencies to undermine local regimes. Translators in Latin America had come under particular scrutiny; some projects were shut down. The rumors followed them to Nigeria.

The Daily Times of Nigeria reported on May 6, 1976, that “the government felt concerned with the activities of the institute.” The Times tied the closing of SIL to the closing of something else: the “US radio monitoring base at Kaduna,” a facility widely known to be a US intelligence gathering operation.

I asked Danjuma Gambo about these allegations, which were never substantiated. “They were just using that as an excuse,” he said. The development of dictionaries, primary schools, and Bibles is a disruptive force, and for millennia, mother-tongue Scripture has irritated the powerful.

“They knew that the work they were doing—the liberation, the development of the local languages—was making people more aware of their rights,” he said.

Nigerian authorities granted the request to retain some foreigners, but only in part.

Three expats were given temporary visas, but only for a year or two. As the NBTT grew and took on exclusively Nigerian translators, only one expat would be allowed to remain long term.

Guess who they chose.

As the NBTT’s new chief trainer and Western linguist, Barnwell made her home in Jos, a temperate, mid-sized city in central Nigeria where the translation organization was headquartered.

But she had begun preparing for the role years earlier.

In the mid 1970s, Nigeria was the 11th most populous country in the world and growing rapidly (today, it ranks sixth). And in the postcolonial era, the African church was exploding. “Between 1964 and 1984 Christian numbers [in Africa] increased from about 60 million to roughly 240 million,” wrote Lamin Sanneh, the late Yale missiologist of Gambian descent. “The irruption of Christianity in contemporary Africa is without parallel in the history of the church.”

In Nigeria—particularly in the southern half, where the British had established numerous universities—many new believers were well educated, quadrilingual and pentalingual. If Nigeria needed scores of translators to bring the gospel to its hundreds of language groups, it wasn’t hard for Barnwell and some of her contemporaries to imagine where the workforce ought to come from.

For instance, John Bendor-Samuel, a founder of the UK arm of Wycliffe and a mentor of Barnwell’s, had in the early 1960s forged partnerships with universities in Ghana and Nigeria to do translation work, the first such arrangements on the continent.

Photos Courtesy of Katharine Barnwell

Photos Courtesy of Katharine BarnwellIn the early 1970s, Barnwell wanted to go further: She wanted to employ Nigerians who were not university-trained linguists, even if it meant teaching them herself.

Unfortunately, there were no tools on the market for that sort of thing. They hadn’t been invented yet.

According to Ernst Wendland, professor of ancient studies at the University of Stellenbosch and one of the world’s leading Bible translation scholars, none of the contemporary published training materials were any good—not for nonlinguists. So Barnwell, several years before taking on her training role with the NBTT, had begun writing her own training curriculum and teaching her first Nigerian translators.

Barnwell leaned on the linguistic theory of influential thinkers like Eugene Nida, Charles Taber, John Beekman, and John Callow. But while they published almost exclusively for the academically fluent, Barnwell translated lofty ideas for people who had never studied linguistics.

For instance, where Nida proposed the hugely influential theory of “dynamic equivalence,” Barnwell coined the term “meaning-based translation”—a simpler and less intimidating door to the same concept.

The training was a clear success. As more and more translation leaders began exploring the idea of training nationals, Barnwell was asked to turn her course into a book. In 1975, she published Bible Translation: An Introductory Course in Translation Principles.

Not everyone in the translation world was smitten with the idea of equipping first-language workers to lead projects. William Cameron Townsend, who founded both Wycliffe and SIL, rejected the notion of having “tribesmen” take charge of translation efforts, believing that Westerners had an obligation to lead the work and not “pass the buck [and] let the nationals do it.”

But in Nigeria, the government was forcing Western hands. And no one was as well positioned as Barnwell was in 1976, when Nigeria purged itself of lettered Western linguists, for the monumental training task that lay ahead of her.

Nearly half a century and four editions later, Barnwell’s book is still the gold-standard manual for training first-language translators (formerly called mother-tongue translators) the world over. I used it in my trainings overseas when I worked as a translation consultant. So has every Bible translation worker I interviewed for this article. (Danjuma Gambo was teaching from Barnwell’s text in Nigeria when he stepped away to speak with me via Zoom.).

Other organizations eventually developed competing materials, according to Wendland, “but none to my knowledge have really succeeded in replacing or in doing something better” than Barnwell’s.

Today, the textbook itself has been translated into more than a dozen languages. It’s given away digitally to pretty much every translator associated with mainstream Bible translation organizations.

“In the old days, you’d have a translation workshop where you’d have someone teaching on semantics, someone on lexicology, some on syntax, some on discourse, and then you’d expect the translators to go out and apply that themselves in their actual work,” Wendland said. But when they opened the Scriptures to begin, they were at a loss. “That’s not the best way to teach translators.”

Instead, Barnwell taught translators to learn by doing. If the old model was deductive, hers was inductive. Barnwell invited first-language speakers to wade into the Bible like swimmers and paddle, becoming skilled in semantics and discourse and other fancy disciplines along the way—without necessarily knowing the names of those fields. In a sense, she discipled her students.

It might seem obvious in light of today’s learning theories, when we just seem to know that you wouldn’t teach swimming on a chalkboard. But at the time, Barnwell’s training was revolutionary, and it multiplied in ways she couldn’t have imagined.

In 1978, Barnwell published the second edition of her book, and shortly after, she began a meteoric rise in the translation world. By 1980 she was overseeing all of SIL’s projects in Africa and spent a dizzying decade crisscrossing the continent, teaching in the UK, and completing the Mbembe New Testament that had been her career’s first love.

Around 1984, Barnwell remembers, is when her book and methods began to see widespread use outside of Africa. As translators trained on her book went on to become consultants and trainers themselves, they spent careers doing the work and raising up new students, who did the same.

Larry Jones, CEO of the translation organization Seed Company, estimated that in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the translators trained on Barnwell’s materials number in the thousands.

To glimpse the full impact of Barnwell’s methods, you have to look not only at her books, but at film. The Jesus film.

For the first 20 years of its existence, the Jesus Film Project, the ministry that distributes the 1979 movie depicting the life of Christ, did not do its own translation work. Instead, it “relied on the people who worked on a translation to work on the script for us,” said Tom Meiner, the project’s chief operating officer.

When the Jesus film staff wanted to expand into a new language, they would reach out to translation agencies and ask, “Do you have anybody? Are you working on this language? Do you have somebody who could work on the script?” Meiner said.

If they heard back at all, they were normally pointed in the direction of a Western missionary. Often, Meiner said, that missionary had since retired or moved on to another project. Or they were dead.

Chris Deckert, the film’s director of language strategies, said that if they found a willing translator, they would send “an Excel spreadsheet with a little manual that said, ‘Hey, missionary, if you could translate these lines here into these lines here, and try to keep the syllable count as close as possible because this is lip-synched…’”

The process was cumbersome. “We’d send off that packet, and maybe a year, two, or three, sometimes they’d get back to us,” Deckert said. The work that did come back could be unpredictable and low quality.

The group wanted to “move forward on languages that had no Scripture and no Jesus film,” Meiner said. “The largest ones that we could get going.” But that would mean doing original translation work, something they were not equipped to do.

In the late 1990s, Paul Eshleman, the Jesus film’s first executive director, met with leaders from Wycliffe and SIL. He cast the vision for a partnership to create a version of the film for each of the 30 largest remaining languages that did not yet have a word of Scripture. The translation agencies would do what they do best, and so would the Jesus film crew. Eshleman offered to fund the 30 projects, to get them moving quickly.

It was ambitious and experimental, and the big agencies were reluctant to get tangled up in it.

“At that time, no one was willing to let this be in their house. There was no home for this effort,” said Seed Company’s Jones, who was also a former vice president at SIL. “Wycliffe wasn’t sure they were ready to do it. SIL was sure they weren’t ready to do it.”

The leaders suggested a young translation organization that might be a better fit, Meiner remembered. It was called Seed Company.

Back then, Seed Company was a startup, birthed in a converted broom closet. “The skunk works of the Bible translation world,” according to Deckert.

Founded in 1993 by a former Wycliffe president, Seed Company was hungry to prove itself. Its focus was on passing the translation baton to the global church and channeling funding to employ national translators instead of Westerners. It jumped on the Jesus film opportunity.

The plan: Work simultaneously across dozens of languages, employ exclusively non-Western translators, and upend how Bible translation had been done for centuries. What could go wrong?

The risk of embarrassing failure was high. They needed a leader fit for the task.

SIL recommended—who else?—Katharine Barnwell.

By then, Barnwell had moved to SIL’s Dallas headquarters and was serving as the organization’s international translation coordinator, arguably the top technical position in the Bible translation world. She was flying from Pakistan to Peru to Papua New Guinea, advocating for the national translators she was training and checking in on hundreds of projects.

Henry Huang, the former director of global strategies at American Bible Society (ABS), told me that to some, Barnwell’s transition to this newfangled film project looked like a demotion.

Barnwell volunteered for it.

In 2000, Barnwell gave up her desk and moved back to Jos and to the NBTT offices in her adoptive Nigeria. There was no better place to test out the film partnership than in the language-rich, population-dense Nigeria.

Because the Jesus film script comes almost entirely from the Gospel of Luke, the film can be adapted quickly once a translation of Luke is finished. Instead of diving into full New Testaments, the norm for that era, Barnwell planned to assemble translation teams from dozens of languages and start them on Luke. Instead of waiting decades for a completed New Testament before producing a new film script, they would only have to wait months.

But Barnwell had something else she wanted to test in Nigeria.

Though she’d long championed the potential of national translators, she wanted to explore how they could work better. Rather than training one translation team at a time, which was the usual practice, why couldn’t she train multiple teams at once? Could she get them started on six languages at once? Twelve? What about 25?

With that question, according to the University of Stellenbosch’s Wendland, Barnwell became one of the early pioneers of what translators call the “cluster model,” a practice that has arguably done more than any other innovation to accelerate the pace of Bible translation around the world.

In this model, translators from dozens of languages across Nigeria descended on the NBTT offices.

Photos Courtesy of Katharine Barnwell

Photos Courtesy of Katharine BarnwellAfter they learned from Barnwell and other trainers, they learned from each other. By sharing notes and ideas in related languages, dialects, and trade languages, they translated in community. They collaborated on difficult concepts and passages. Solutions flew across related languages.

In only weeks, they developed orthographies for languages that had never been written. In less than three years, they completed the Gospel of Luke in several languages. After that, they could adapt, syllable match, and record and edit the Jesus film in a new language in only a month.

Although a number of translation consultants around the world were beginning to explore the cluster approach in the late 1990s, multiple people I interviewed said Barnwell was the first to systematize it and apply it at such a large scale.

The Jesus film’s translation project helped revolutionize Scripture use, Deckert told me. Some Bible translators labor for 30 years to produce a New Testament that nobody cares to read. But with the local churches driving the process, local believers took pride in the project and then used the film and Luke for evangelism, preaching, and teaching. Many of those Luke partnerships went on to become larger projects: full New Testaments, audio story sets, audio Bibles, and even full Bibles.

Within a decade, “it was working all over the world,” Deckert said. Around 2012, the Jesus Film Project adopted Barnwell’s model across the globe as its standard method.

“We almost tripled the number of Jesus films produced per year,” Deckert said. “It was just crazy.”

They were no longer working in languages with existing Bibles; the growth was happening in languages without a single written word of Scripture, or without any writing system at all. What Barnwell accomplished “is still regarded as nearly miraculous,” said Jones, the Seed Company executive.

Today, the Jesus Film Project has produced 2,005 translated editions. In 2010, they were coming together so quickly under Barnwell’s model that Deckert had to set a new goal: to produce the film in the world’s 865 remaining languages that have over 50,000 native speakers but no Scripture. Even despite the disruptions caused by COVID-19, he says they’re on track to hit that target in the next three years.

The Jesus Film Project says more than 633 million people worldwide have “indicated decisions for Christ following a film showing.” More than half of those—361 million—were counted after the ministry began using Barnwell’s methods, according to its records.

Even with some padding for optimism, that’s a remarkable number. By comparison, nearly three million people are estimated to have become followers of Jesus after listening to Billy Graham’s sermons.

But if you’re the type that’s suspicious of conversion statistics, you could attempt to size Barnwell’s legacy in terms of Bible translations.

Using conservative estimates, the number of languages in the world with full Bibles has more than doubled in the past 25 years, from 308 in 1996 to 717 as of 2021, according to Wycliffe UK. This happened when Barnwell’s trainees and methods were already in full force. Her book was 10 years into its third edition by then, used around the globe.

Since then, the number of New Testaments has exploded, and the number of languages with portions of Scripture (but not yet a complete New Testament or Bible) has increased by 2,000.

According to Wycliffe UK, “there is also active translation or preparatory work going on in 2,617 languages in 161 countries. Wycliffe and its partner organization SIL are involved in about three-quarters of this work.” Not to mention their other partner organizations that use Barnwell’s teaching and are staffed by her trainees.

“I don’t think there’s anyone in SIL, Lutheran Bible Translators, UBS [United Bible Societies], the Seed Company, Pioneer Bible Translators—any of those—who have not been in contact with Katy’s thinking, writing, and teaching,” Lynell Zogbo, an author and retired translation consultant in Africa, said in a 2020 interview.

Even translation projects not directly interacting with her materials still swim in the global currents set by Barnwell’s training, teaching, shepherding, students, methods, and journal articles. Hundreds of millions of new global Christians are taught with Bibles that might not exist without her.

“Her fingerprint is everywhere,” Deckert said.

Has there been a single translator in church history with Barnwell’s sway? We could talk about Jerome and his Latin Vulgate, used by the Roman Catholic Church as its principal translation for over 1,500 years. There was Luther and his German-language Bible. There was England’s King James I, if you credit him for commissioning his KJV—or William Tyndale if you feel like the KJV was mostly cribbed from his work.

But in 200 years, when the beating heart of world Christianity thrums from Nigeria and China, the reach of those Bibles may pale beside the ones Barnwell equipped the Global South to translate.

I asked more than a dozen translation leaders, scholars, and practitioners: Has anyone in modern history had Barnwell’s direct impact on translation?

All reached a similar conclusion: “I can’t think of anyone,” Jones said.

Only two names were consistently mentioned in the same breath as Barnwell’s: Eugene Nida and William Carey.

Nida, the influential theorist, trained translators all over the world and is said to have helped shape translations in more than 200 languages. Like Barnwell, his influence transcended organizational boundaries.

Carey was a polymath—a linguist, a translator, an anthropologist, a publisher, a school founder, a seminary founder, and a translator of full or partial Bibles in 30 or more languages.

I might add Kenneth Pike, the president of SIL from 1942 to 1979, a leading linguistic scholar, and an early pioneer in the field of English as a second language, or ESL. According to SIL, he was nominated 16 times for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Not bad company.

“She would die a thousand deaths if you put that in print,” said Teryl Gonzalez, a former student of Barnwell’s and now the strategic quality assurance development consultant at Wycliffe US.

Why not pose the question directly to Barnwell? Is it possible that she is as influential as everyone says?

“Well, it may be true,” Barnwell admitted over Zoom, frowning at the question. “But I don’t want to talk about that.”

Photos Courtesy of Katharine Barnwell

Photos Courtesy of Katharine BarnwellShe never worked alone, she said. All of her accomplishments happened on teams. She said it was simply a privilege to serve in what was so often the right place at the right time—to have been placed at the crossroads of history.

“She is the mother of Bible translation in Africa,” said Olivia Razafinjatoniary, a Malagasy language consultant serving across that continent.

For all of Barnwell’s titles, “Mother” is the one you’ll hear most often among those who know her—or “Mommy Katy.”

It’s not merely courtesy. Especially for the many women who have known Barnwell—who never married and has no children—the title is maternal.

In Razafinjatoniary’s case, Barnwell changed her life.

It was the year 2000, and Razafinjatoniary had just finished graduate studies in translation when she was on a bus in Nairobi, Kenya, and told someone who happened to work in Bible translation, “I really want to give back to the Lord what he gave me.”

Shortly after, Barnwell got in touch from her office in Nigeria about a project launching in Razafinjatoniary’s home country of Madagascar. Did she want to be trained?

“She would fly to Madagascar twice a year to train me,” Razafinjatoniary said. “I would observe her working, observe other consultants working. She was very encouraging, and she really believed in me from day one. That pushed me to where I am now.”

Razafinjatoniary dedicated her second master’s degree to Barnwell.

“My desire from day one was to become like her,” she said. “We have been in touch, even now. She knows all about us. We know all about her. When she’s sick, we know. When she’s well, we know. When she’s traveling, we know.”

For Barnwell, her colleagues are her family. “They were the children God gave her,” Jones said.

Consider, for example, a typical month in Nigeria as painted by Gonzalez from her time working with Barnwell: Eighty translators from 25 different languages might converge upon Jos for one of Barnwell’s “one-book workshops.”

“Every one of those people saw her as a mentor, a mother, a benefactor in some way,” Gonzalez said. Barnwell was almost always wearing a light blue dress, and “every time you turned around, somebody was knocking on her door. Coming to greet. To express their affection.”

Barnwell had a reputation for forgoing creature comforts. She was known to sleep on hard floors when traveling and give colleagues food off her plate. She often put in 12-hour days—running workshops, making tea for visitors at all hours, and checking translated Scripture passages in between.

Her extended Christian family, built through countless such encounters, spans the globe.

Gonzalez told me that, at a recent Bible translation conference she attended, the emcee asked for a show of hands: Who in the auditorium had been personally shepherded, helped, trained, or ministered to by Barnwell?

Hundreds of hands shot up, belonging to translation leaders from every inhabited continent.

Gonzalez was one of them.

She had dreamed of becoming a consultant—training, teaching, checking passages—since she was 15.

Many years and a handful of graduate degrees later, Gonzalez did it: She became a consultant. While she was coming up, the minimum qualifications were “a million years” on the field as a consultant in training and preferably finishing your own New Testament.

“Like an oak, you just grow for 100 years and then you’re an oak tree,” she said.

Gonzalez’s second son, however, was born with serious medical issues that required her and her family to leave a translation project on the other side of the world and return to the States.

In a moment, she went from missionary to a “stay-at-home mom with preschoolers in suburban Seattle. Everything just stopped for a long time.”

But Barnwell was making a place for her.

During her time as SIL’s international translation coordinator in the 1990s, Barnwell had begun reducing the amount of time required in the field to become a consultant—from decades to only a few years. She wanted a new generation of first-language translators to rise through the ranks, and she needed Westerners to train them. As Barnwell saw it, if workers could prove their skills, why hamper them with the burden of fundraising for half a lifetime overseas?

The shift allowed for the formally educated Western Bible professor and the gifted national translator to both become consultants based on consistent quality work in the field.

All the while, the internet and communications technology were maturing. By the time Barnwell was running the Jesus film’s translations in the early 2000s, she felt that, in the age of videoconferencing and affordable laptops, translation consultants should not have to leave the profession to care for aging parents or sick children.

So she began inviting sidelined consultants back to work with her a few weeks at a time.

Before Barnwell, “most of these would go home and serve in administrative roles or recruiting roles or something like that, but she felt like that was such a loss of talent and resources,” said Huang, the former ABS director who had also worked with Seed Company.

It reopened doors for people like Gonzalez, whom Barnwell invited to Nigeria in 2010 to work there with her a few times a year.

Combined, the changes opened doors for workers from the Global South, hundreds of whom have been recognized and promoted in this modernized culture, Jones told me.

Barnwell’s long career training first-language translators and putting project ownership into local hands has born its fruit: Bible translation has become so thoroughly democratized that no one today seriously debates whether nationals should lead the translation process.

Instead, in an unrelenting push to make Bible translation faster and cheaper, new reformers have asked different kinds of questions.

Are trained translation consultants really necessary? Couldn’t thousands of passionate Christians sitting in internet cafes work together online to translate a book of the Bible from a major trade language into their first language?

Translation groups—including Seed Company and Wycliffe Associates—have dabbled with experimental approaches to rapid translation: things like wiki-style community translations; using artificial intelligence, software, and algorithms; or crowdsourcing rather than looking to trained workers or scholarly resources.

In an interview in the Journal of Translation, Barnwell criticized the constant quest for a “quick and dirty solution. … Quick translations without thorough grounding, careful study, and application of sound translation principles are just a waste of time.”

For the most part, the translations these experiments produced have been abysmal. But they have not been fruitless.

“One of the most effective things they were doing was energizing these local communities,” said Brian Kelly, Seed Company’s director of Bible translation exploration. “They’d say, ‘Hey, wow, we could all be a part of this.’”

Tim Jore works with unfoldingWord, an Orlando, Florida, group that helps churches around the world translate Scripture themselves. Jore believes the translation industry should focus less on minting new Bibles as if they were a product and focus more on empowering Christian communities to produce their own Bible translations. Historically, he argues, translation has been the work of the church.

“When a new English translation of the Bible is published,” Jore wrote in a widely shared paper, “the English lingual church does not look to translation consultants to approve it.”

English-speaking church leaders and scholars have the knowledge and the tools they need to approve their own translations. The global church should, too. And it could, Jore argues, if Bible translation organizations shifted their methods away from product-centered thinking and toward equipping the global church to manage its own quality assurance.

This approach is called church-centric Bible translation, and Jore feels it’s the logical conclusion of the changes Barnwell set in motion.

Her work “laid an important foundation for the next major transition in Bible translation that is happening all over the world today: Bible translation done by the church to meet their own theological and discipleship needs,” Jore told me.

When I asked Barnwell for her thoughts on church-centric translation, she was cautiously positive. “The focus on the involvement of churches in the receptor language area is not new and cannot be overemphasized,” she said.

But she also stressed the missionary importance of translation, “to explore what can be done to promote and support translation work in language areas where there are as yet no believers, no church.”

In other words, church-centric translation is great, but who will go to the places with no church? The great test of the church-centric paradigm may not be whether churches can translate Bibles for themselves, but whether they expand their translation efforts into regions where there are no believers—without the assistance of Western missionaries or the prompting of their translation organizations.

“We share the same goals,” Barnwell said, “to see high-quality translated Scriptures available for every language group as soon as possible.”

Barnwell herself has now become a beneficiary of the democratized translation culture she helped to create. It has served her over the past decade as she’s eased back down the ladder, slowly handing her leadership responsibilities over to a constellation of workers in Nigeria, the UK, and the US.

A number of years ago, she moved back to her UK home, Goring-on-Thames, about 50 miles west of London. She’s once again working with the Mbembe, the people she lived among when she first moved to Nigeria to translate the New Testament. Her earliest friends there are long passed, but the next generations of the local church—many of them raised on her New Testament—are collaborating with her on three related Old Testament translations.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Barnwell made regular trips to visit. But with her worsening osteoarthritis, she stays put in the UK and works through Zoom. She jokes that she “travels to Nigeria every day.”

To fill whatever spare time that leaves, Barnwell is also sharpening up her Hebrew and training two Nigerian consultants.

There’s debate among her colleagues over how many people it will take to replace her when all is said and done—if she actually retires.

“It hasn’t been without pain for her, but I have seen such a spiritual maturity and humility in her as she has navigated” stepping back, said Jones, the Seed Company executive.

In 2015, around the time Barnwell was relinquishing her leadership roles and passing the baton to national colleagues, the largest Bible translation organizations in the world, together responsible for about 85 percent of Bible translation worldwide, banded together to agree on what they called the “Common Framework.”

It was a kind of industry-wide best practices agreement. In short, it stated that instead of Western translation agencies running the process, the global church in its local manifestations would own, direct, perform, and be the “end users” of Bible translation. Locals would decide which Scriptures to translate, in what medium—audio, written, visual, or sign language—and in what order. Western partners would act in a consulting and helping role.

For those who worked with Barnwell, it might have all sounded like pretty old news. It’s what she’s been doing since the 1970s.

So, will she ever really retire?

“What else would I do?” Barnwell said. “Would I just sit and twiddle my thumbs? I enjoy my work, and I’m glad that I can still do it. And I’m very thankful that the physical problems of old age are not in my head so much as in my legs.”

But say, for argument’s sake, that she did retire. Is there possibly anything more the African continent and the world’s hundreds of remaining Bibleless peoples could ask of her?

Larry Jones remembers a story.

He was crammed into a car with a few too many people riding from Jos to Abuja, Nigeria’s current capital. Barnwell was sardined next to him. At one of the many military checkpoints that lined the highway, a soldier with an automatic rifle on his shoulder halted the car.

He scanned the passengers and began to interrogate the driver. The tone was tense. The soldier bent down and scanned the passengers again, catching someone he seemed to have missed the first time.

“He leaned over, with his head into the window,” gun barrel trailing him into the car, Jones said. When the soldier’s eyes landed on Barnwell, “his demeanor changed almost 180 degrees.”

The soldier flashed a huge smile and said, “Pray for us, Mother.”

Jordan K. Monson is an adjunct professor at the University of Northwestern–St. Paul, a former Bible translator with Seed Company, and the pastor of Capital City Church in St. Paul, Minnesota.