When he watched Billy Graham preach, David Bruce couldn’t help but think of history.

As executive assistant to the famous evangelist, it wasn’t Bruce’s job to think about the distant future—Graham’s legacy, how he would be remembered after he died, how the evidence of his life’s work would be maintained—but he thought about it all the time. Each word and moment seemed so significant that it needed to be preserved.

“When he finished preaching, I would come behind him and gather the pages of his sermon,” Bruce recalled this summer, four years after Graham’s death. “He was not thinking of that. But I could see the call of God on his life and all the history he touched.”

Today, Bruce oversees a state-of-the-art monument to the preservation of that history: a 30,000-square-foot, $12 million archive. It will open on November 7, Graham’s birthday.

A well-lit research room sits quietly on the first floor of the building. It was constructed in consultation with archival design specialist Michele Pacifico and now waits for historians to come and ask for boxes and files. Upstairs, in a carefully climate-controlled room, industrial shelves hold thousands of acid-free archival containers, each with hundreds of papers. Another room houses oversized items, from a pair of gifted lederhosen to Graham’s traveling pulpit.

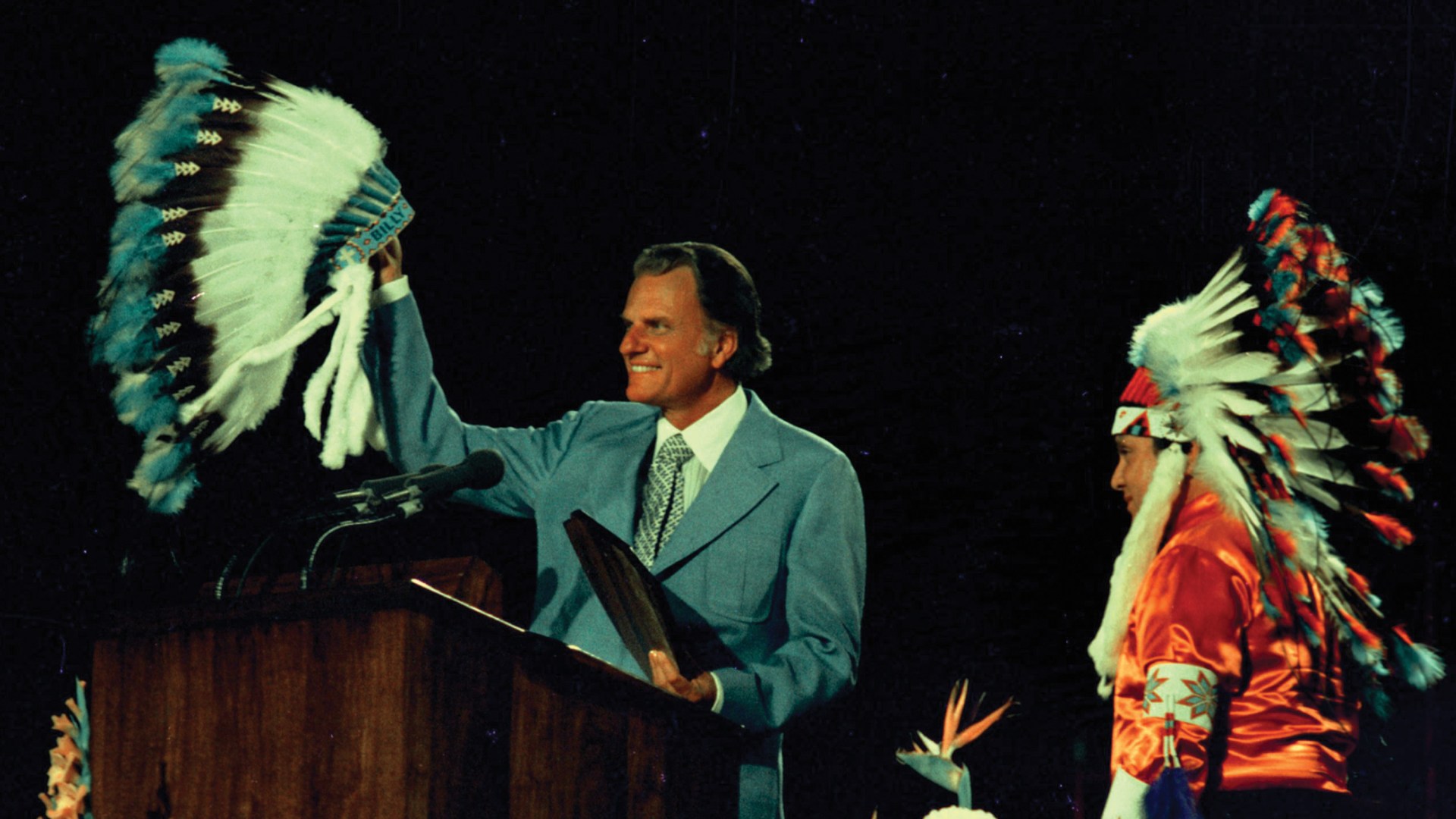

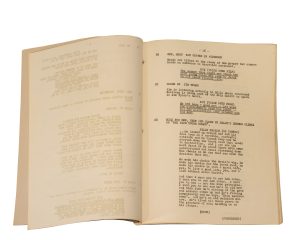

Courtesy of the Billy Graham Archives

Courtesy of the Billy Graham ArchivesThe Charlotte, North Carolina, research facility, located across the road from the Billy Graham Library museum, gathers for the first time the full documentary record of Graham’s life and work in one place. The archives that were loaned to the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College will be combined with the hundreds and hundreds of boxes that remained at Graham’s home office in Montreat, North Carolina, and additional material from his ministry’s former offices in Minneapolis and in storage in Charlotte.

“We’re really trying to make everything as accessible as possible,” said archivist Lindsay Elliott, who previously worked at Jimmy Carter’s presidential museum in Atlanta. “We want to offer the full breadth of his ministry, from the material at Montreat to the productions of World Wide Pictures. We’re describing and classifying everything. We want to look at the entirety of it.”

When plans for the new archives were announced in 2019, a year after Graham died, professional historians expressed deep concern. They worried the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) might not care for the material as well as the professionals at Wheaton and—more upsetting—that the BGEA might sharply limit access.

Private collections sometimes prioritize the preservation of a reputation over open scholarship. This is especially true when the holdings are overseen by family or close associates. They may vet researchers, denying access to those they deem too critical. They may keep sensitive documents out of sight.

Elliott and Bruce, however, say the Billy Graham archives will be open to all scholars, students, and researchers and will be run professionally.

Graham’s legacy is contested in 21st-century scholarship. Some see him as an example of the best of evangelicalism and want to measure others against him. They point out how he was irenic, inclusive, pragmatic, and focused on Jesus. They say he made mistakes and did some reprehensible things but learned from them and was humble enough to actually apologize.

“Graham was not a marble statue,” biographer Grant Wacker writes in the introduction to America’s Pastor, “and he was the first to say so.”

Other historians argue a more careful examination of the record shows Graham participated in the worst parts of evangelicalism and he’s just been given a pass. They’ve called for a more critical look at his involvement in American politics, his positions on race (including antisemitic statements recorded in conversation with Richard Nixon), and his views on women.

There’s a popular struggle over the meaning of Graham, too. As political issues have raised the temperature of internal evangelical debates, people on both sides have appealed to Graham’s memory. Some of his grandchildren, for example, used his legacy to critique support for Donald Trump. But eldest son and BGEA president Franklin Graham said the evangelist voted for Trump in 2016 and believed he was “the man for this hour.”

The archive and research center isn’t designed to settle contests over Graham’s legacy. It will not fix the evangelist’s reputation in time. It’s built, instead, to contest time.

In his own lifetime, Graham was famous and frequently named one of the most respected men in America. When people thought about what it meant to be an evangelical Christian, they thought of him.

Courtesy of the Billy Graham Archives

Courtesy of the Billy Graham ArchivesBut famous evangelists fade from memory quickly. Billy Sunday is not a household name anymore, even among evangelicals. He preached to an estimated 100 million people, but his museum, located in Winona Lake, Indiana, has struggled to stay open. The ephemera of Charles Finney’s life and work—including pieces of his revival tent and a phrenological chart of his head—are kept in 12 or 13 boxes at Oberlin College in Ohio.

In Charlotte, though, archivists on Elliott’s team will prepare fresh, new exhibits for the neighboring museum across the road. Since it opened 15 years ago, the Billy Graham Library has welcomed more than 1.7 million visitors, including those who attended Graham’s funeral in 2018. Tripadvisor ranks it the No. 1 thing to do in Charlotte, with more than 80 percent of visitors giving it five out of five stars.

In another room of the archive, audio-visual archivist David Eades will oversee the production of 10 to 25 “Billy Graham TV Classics” to air on TBN and stream on Roku and Amazon Prime. Old crusades with old altar calls will be given another chance to reach people, and Eades and his team will also look for ways to make Graham’s life and message relevant to current events. In September, a new special on Graham’s relationship with Queen Elizabeth II aired across the US and the British Commonwealth.

This isn’t just nostalgia, Bruce insists. It’s not history for history’s sake either.

“Mr. Graham wouldn’t have approved of any of this unless it could be used to further the gospel,” he said. “I hope that people see the work of God in his life, and then all the history he touched, and it can encourage people to reflect on the living, breathing Word of God.”

Daniel Silliman is news editor for Christianity Today.