As I write this, Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison spins on the record player, filling my living room with the driving, train-like rhythms of one of America’s greatest storytellers. Originally released in 1968, it’s one of the dozen vintage Cash albums we inherited when a friend from our small working-class community moved to be closer to her children. Moments into the eponymous “Folsom Prison Blues,” a lyric catches my attention:

When I was just a baby my mama told me, “Son,

Always be a good boy, don't ever play with guns.”

But I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die

When I hear that whistle blowing, I hang my head and cry.

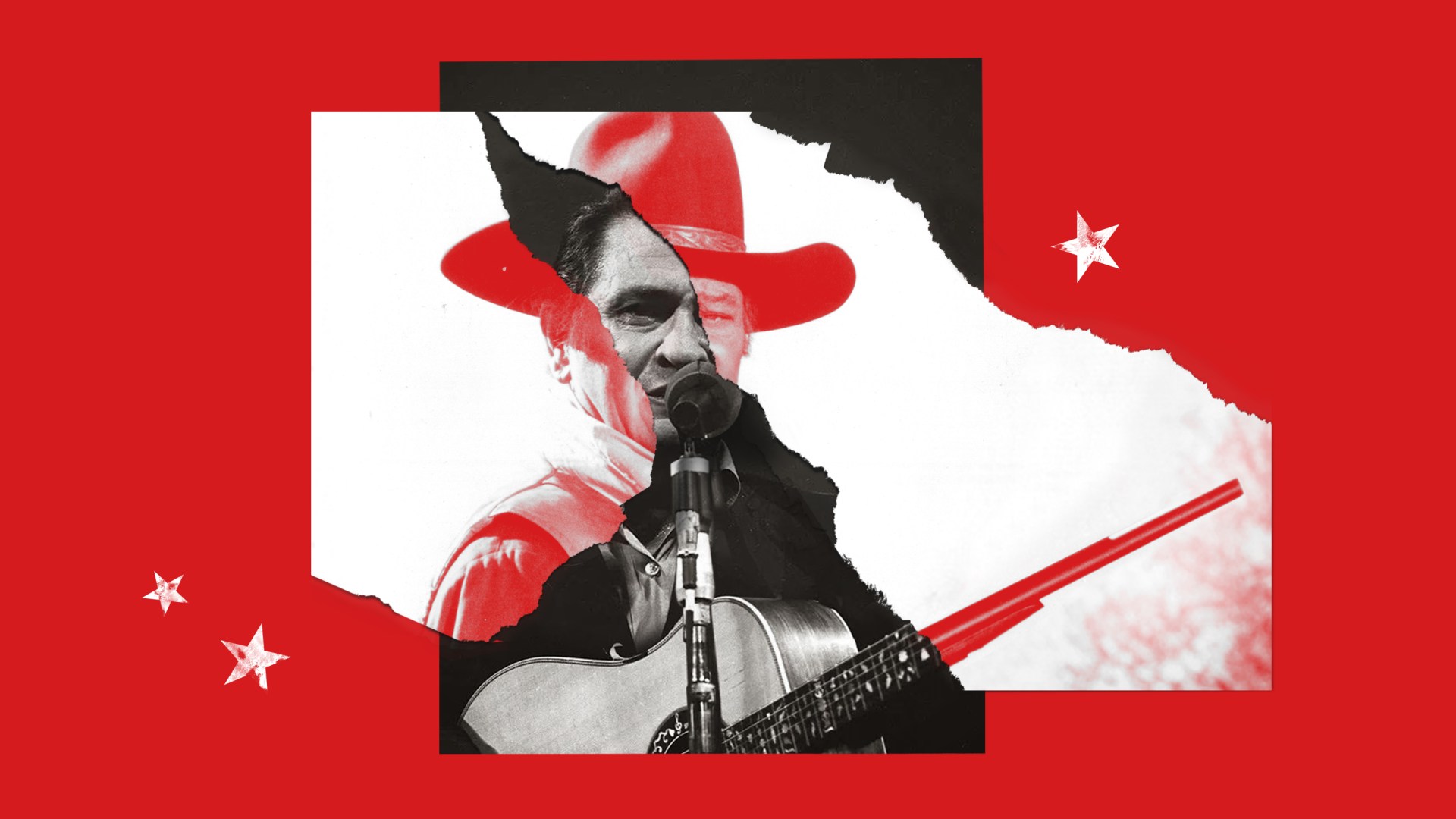

And there it is: a voice from the past describing the past few weeks of horror in the United States. From Buffalo, New York, to Uvalde, Texas, to Highland Park, Illinois, we are once again grappling to understand what has become an all-too-common atrocity: senseless mass shootings by disaffected, violent young men. As a mother to a 16-going-on-37-year-old son, I think a lot about the state of manhood in American society and the evangelical church. Much has been made of the excesses of John Wayne masculinity, but I wonder if it’s time for a conversation about Johnny Cash masculinity.

While The Duke is synonymous with true grit, masculine bravado, and dominance, The Man in Black offers an alternative vision—and perhaps a way forward in these deeply fragmented times. Cash’s roots ran deep in the American South, and themes of poverty, religion, and all things Americana informed his music. His biggest hits include sentimental ballads about riding the rails, the mythical Wild West, and hard-working, hard-living men who miss their mamas. But while Cash celebrated a kind of rugged masculinity, he was also a deeply-flawed man. His life was marked by infidelity, alcoholism, and drug abuse. He was no pastor. And yet, Cash had a singular advantage—something the current rhetoric around masculinity misses. He knew he was a deeply flawed man. He knew he was a man in need of grace. So while he sang about the temptations that are common to all, he didn’t justify or excuse his own participation. Instead, his discography rings with confession, grief, and cries for redemption.

In the aforementioned “Folsom Prison Blues,” the narrator speaks of his criminal sentence as just and good. He confesses, “I know I had it coming, I know I can’t be free.” And just listen to Cash sing Kris Kristofferson’s “Sunday Morning Coming Down,” a song about the spiritual alienation and deep loneliness of hard living, and try not cry. Cash’s vision of masculinity is not a clean, controlled manhood. It is not even moral by classic definitions, but it holds the seeds of virtue because it is humble and self-aware. With King David, another broken poet-warrior of a man, Cash sings in so many words: “I know my transgressions, and my sin is always before me” (Ps. 51:3). This juxtaposition of a rough-around-the-edges manhood that is also deeply humble challenges what David French terms “The New Right’s Strange and Dangerous Cult of Toughness.”

In a recent essay at The Dispatch, French notes that “The debate [around masculinity] is corrupted by politics, with different versions of masculinity now so thoroughly identified as Red or Blue that you can quite often guess how a man votes by the clothes he wears, the vehicle he drives, and the way he describes what it means to be a man.” But Cash throws a wrench into the politics of American manhood. He is not tame or domesticated—after all, he cultivated an outlaw image. But he also didn’t toe the party line, and by contemporary definitions, he would likely have been considered woke. His music reflects a deep compassion for those on the margins. It’s almost as if knowing his own faults made him slow to judge the struggles of others.

While would-be populist leaders claim to be fighting for the little guy, Cash knew that the little guy was more likely to be found in a prison, at the front lines of war, on the factory floor, or neglected on a reservation. And he wasn’t afraid to say so. His 1964 recording of “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” challenged the US government’s treatment of indigenous people and was initially blackballed by both Cash’s own record label company and radio stations across the country. And in perhaps the most quintessential Cash song of all, the 1971 “The Man in Black,” he sings of social injustice that holds people back:

for the poor and the beaten down

Living in the hopeless, hungry side of town

I wear it for the prisoner who has long paid for his crime

But is there because he’s a victim of the times. …for the sick and lonely old

For the reckless ones whose bad trip left them cold

I wear the black in mourning for the lives that could have been

Each week we lose a hundred fine young menAnd I wear it for the thousands who have died

Believing that the Lord was on their side

I wear it for another hundred thousand who have died

Believing that we all were on their side.

Today, over 50 years later, swagger and bravado too often masquerade as masculinity, and folks will tell you there is a war on manhood. But take it from me, someone who grew up surrounded by salt-of-the-earth, flawed-but-humble men: The problem isn’t masculinity. The problem is a version of manhood that refuses to take personal responsibility and celebrates a win-at-all-costs triumphalism.

These vices are what make conversation and cooperation impossible. These vices are what wreck families, churches, communities, and countries. If we’re to make any progress on gun violence, or a host of other issues tearing our country apart, we must identify the real source of the problem. The conflict is between pride and humility. The conflict is between those who own their faults and confess them and those who refuse to admit wrong. It’s between hearts that are softened by the plight of their neighbor and those that are hardened.

Later in his life, Johnny Cash had something of a come-to-Jesus moment. Although he’d been raised and baptized in a Southern Baptist church, he rediscovered personal faith after his marriage to his second wife, June Carter Cash.

He eventually toured with Billy Graham, made several gospel albums, and in an ultimate expression of grassroots evangelical culture, took a trip to the Holy Land. The front of the album commemorating this trip is emblazoned with a holographic image of Cash standing on the Mount of Beatitudes. It’s hard to know how much of Cash’s public persona translated to his private life, and if you read through his body of work, you’ll likely find more than one objectionable lyric. Like the United States itself, he was a man of deep challenge and contradiction. But what you will also find is a vision of masculinity that is honest and humble. You’ll find a vision of masculinity that embraces the complexity of the human condition while refusing to blame-shift, whine, or deflect responsibility. You’ll find a vision of masculinity that knows its need of grace. In a word, you’ll find a real man.

Hannah Anderson is the author of Made for More, All That’s Good, and Humble Roots: How Humility Grounds and Nourishes Your Soul.