Birth rates in the United States are near record lows, but not for everyone.

Under the surface of the fertility decline is a little-noticed fact: Births have declined much more among nonreligious Americans than among the devout.

Data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) from 1982 to 2019, along with data from four waves of the Demographic Intelligence Family Survey (DIFS) from 2020 to 2022, point to a widening gap in fertility rates between more religious and less religious Americans.

In recent years, the fertility gap by religion has widened to unprecedented levels. But while this difference may comfort some of the faithful who hope higher fertility rates will ultimately yield stable membership in churches and synagogues, these hopes may be in vain. Rates of conversion into unfaith are too high, and fertility rates too low, to yield stable religious populations.

Past religious fertility

Since 1982, the NSFG has asked respondents about their religious attendance and their recent fertility history. In recent years, it has operated as a continuous annual survey.

As a result, data from over 70,000 women surveyed from 1982 to as recently as 2019 can be used to estimate fertility rates for three broad groups of women: those without any religious affiliation, those with religious affiliation but less than weekly attendance, and those with at least weekly attendance.

Total fertility rates are estimated by using a given group’s current birth rates by age to guess how many children a woman would end up having over the course of her life. In practice, however, birth rates shift as women get older, and of course religious identity can change over time, as well, so fertility measures of this kind are unlikely to perfectly predict outcomes.

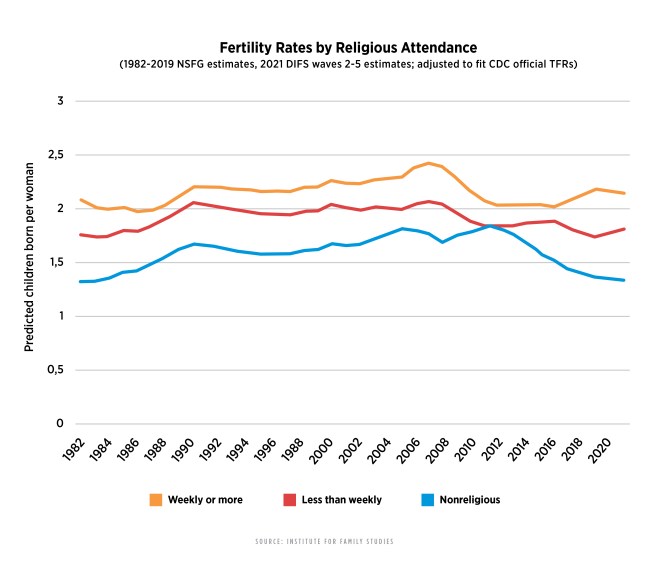

Figure 1 shows estimates from the NSFG for the three religious attendance groups.

It’s evident that birth rates among Americans who attend weekly have never dropped much below 2 children per woman, and as recently as 2008 were around 2.4 children each. Fertility among religious people did decline after the 2008 recession, but by 2017–2019, it was rising again.

In other words, there was no long slump in births to the most devout parents.

Religious women who attended church less than weekly had lower fertility in all time periods but especially during the 2000s. What’s most striking is that, since 2016, fertility rates for weekly- and less-than-weekly-attending women have moved in opposite directions, with fertility falling among the more nominally religious.

Finally, fertility among nonreligious women rose considerably from 1982 to 2005, then again from 2008 to 2012, showing a very different pattern than the one we see for religious women.

From 2010 to 2013, nonreligious women had about the same birth rates as women who attended religious services less than weekly, before their fertility slumped through 2019.

Here’s the most notable takeaway: Virtually 100 percent of the decline in fertility in the United States from 2012 to 2019 can be explained through a combination of two factors: growing numbers of religious women leaving the faith, along with declining birth rates among the nonreligious.

Before going further, it’s worth reflecting on the large cultural difference this represents. In 2019, most religious Americans had similar fertility rates as women in India, Libya, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Iran, Myanmar, Saudi Arabia, Peru, or Mexico. That same year, the least religious Americans had birth patterns similar to Hong Kong, Japan, Portugal, Greece, Italy, Singapore, or Moldova.

COVID-19 has not reduced these differences. From fall 2020 to spring 2022, across four waves of the DIFS (which included about 9,000 participants), women who never attended church reported a fertility rate of around 1.3 children per mother, versus 2.1 for women who attended weekly. Those rates are very similar to the ones found in the NSFG for 2019.

Declining religion in America

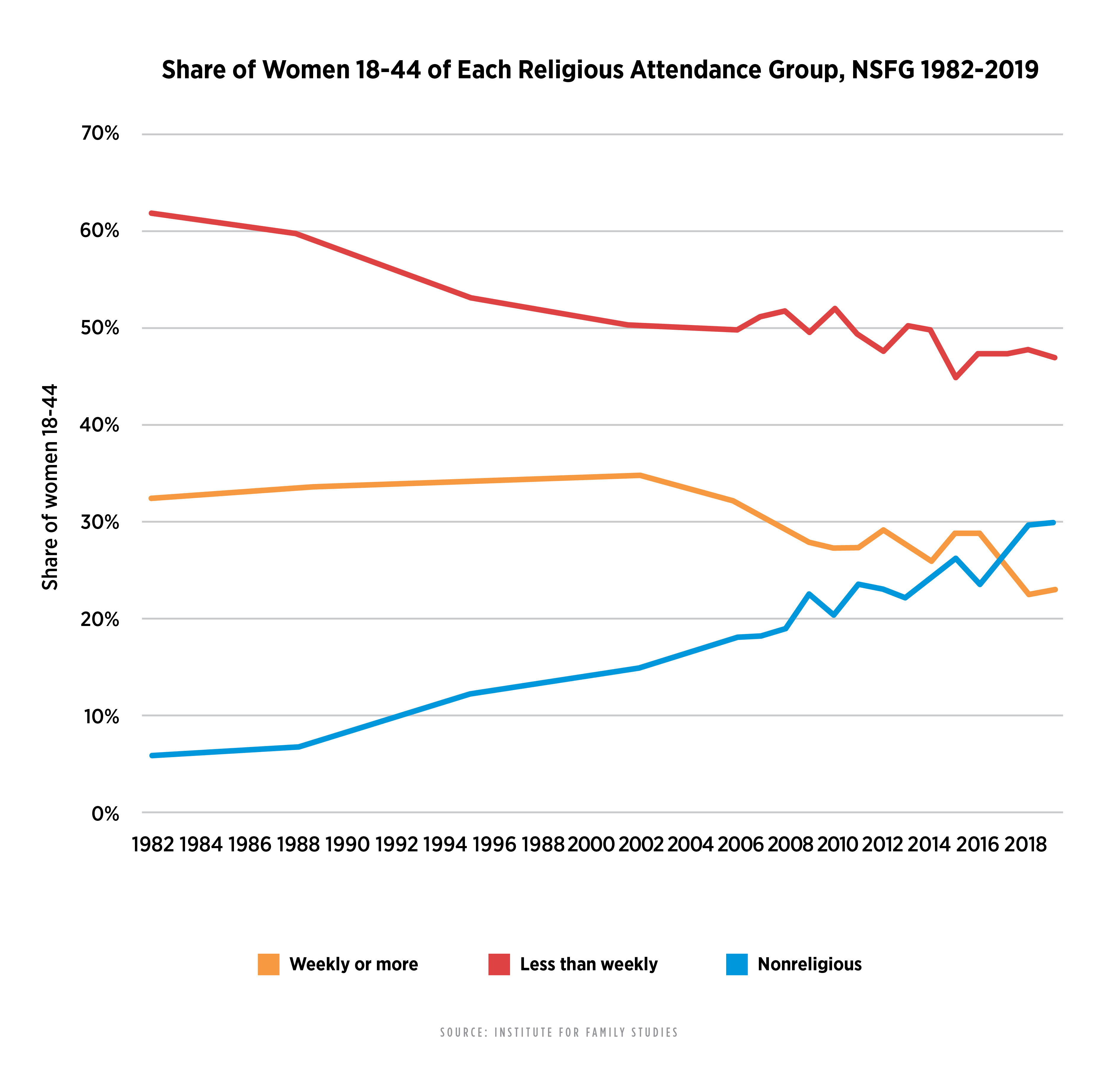

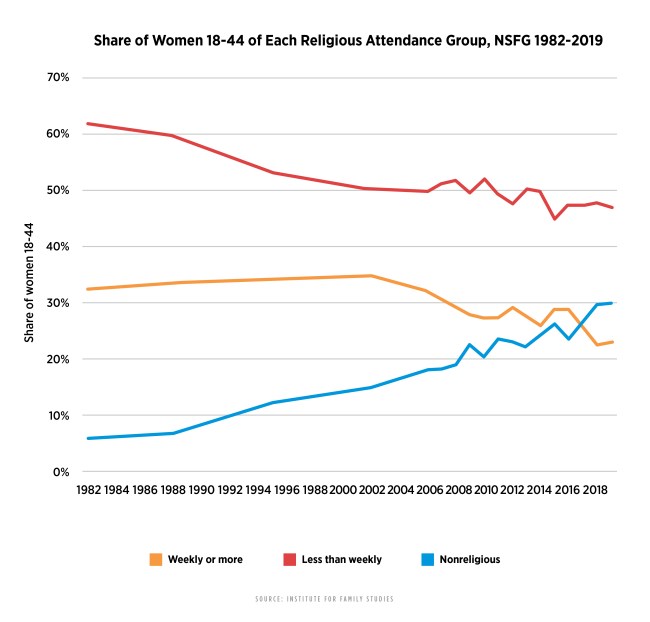

But fertility rates aren’t the only thing driving birth trends. The number of women to whom those rates apply may vary as well. Figure 2 below shows the share of women ages 18–44 who were in each religious grouping, according to the NSFG.

Since 2002, the share of reproductive-age women who attended church weekly or more has fallen from about 35 percent to 24 percent. In the DIFS data, the share was even lower: only about 18 percent of women.

In other words, while the fertility rate among religious women has been stable, society has still become less religious on the whole, meaning the overall number of births to religious mothers has trended downwards.

Here’s the second striking takeaway, then: Despite a widening fertility gap, the ongoing trend of young Americans becoming more secular more than offsets the fertility advantage enjoyed by people of faith. Religious birth rates simply are not high enough to offset losses from the move to irreligion.

Data from the 2014 Pew Religious Life Survey suggest that net conversions in and out of American religions lead to about a 16 percent loss in religious people over the course of a generation. To offset that, religious American women would need to have 2.44 children each on average.

Among weekly attending women, the true figure is just 2.1. If we add in women who are irregular attenders to count all people of faith together, then religious women in 2019 had a fertility rate around 1.8 or 1.9 children each.

With birth rates at just 1.8 or 1.9 children per woman, versus a conversion-adjusted “replacement rate” of 2.44, religious communities in America will tend to decline by about 25 percent in each generation.

If these trends continue, then within three generations, religious communities in America will have shrunk by more than half—a devastating loss.

Key differences across religious groups

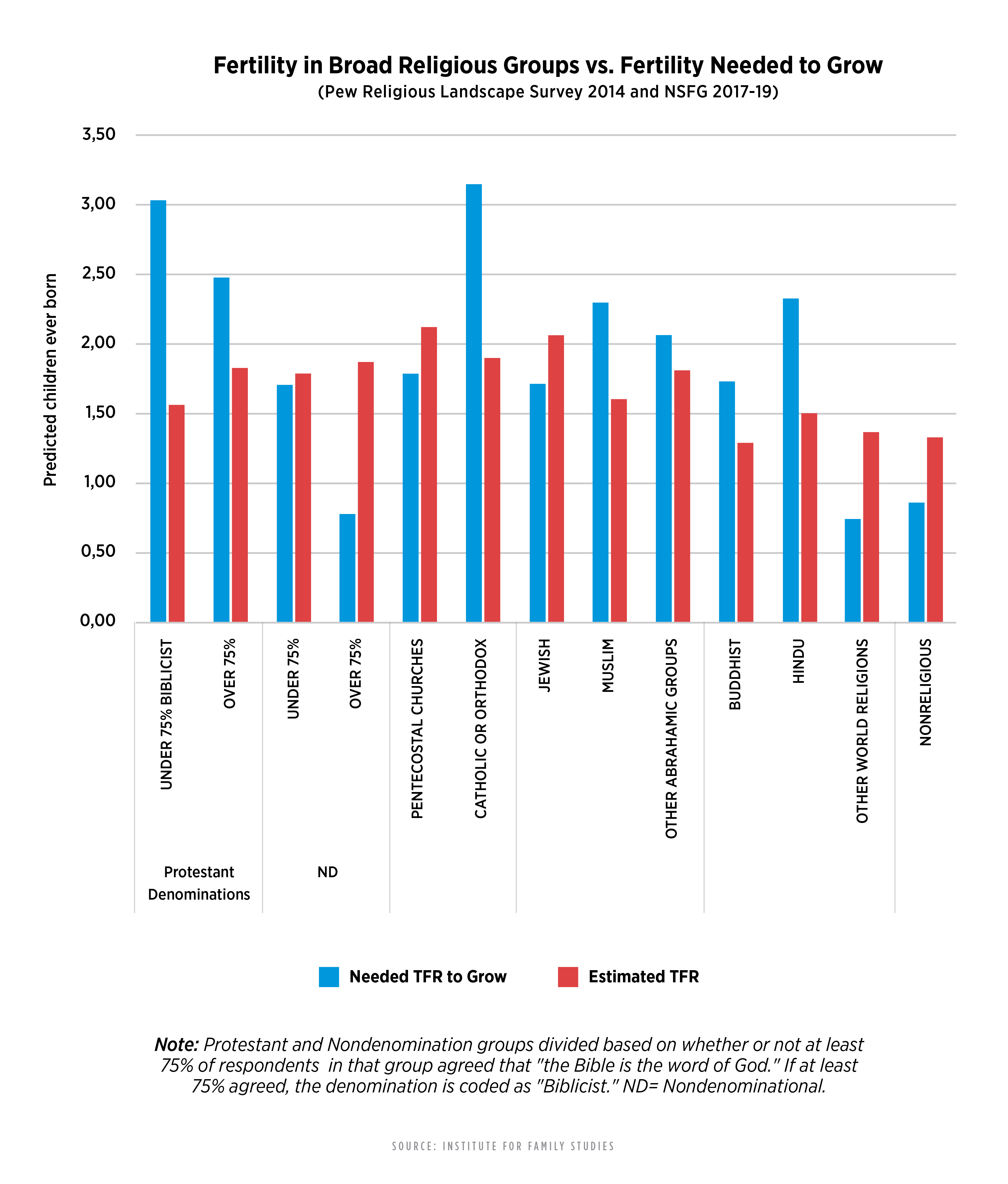

However, it’s not right to lump all religious groups together when it comes to fertility. Using data on conversions and births from the Pew Religious Life Survey (PRLS) in 2014, it’s possible to describe some crucial differences.

Using data from the PRLS, I separated individuals from different major world religions, and within Christianity, I broke out six distinct subgroups: Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox (grouped together, since there are few Orthodox respondents); Pentecostals; Protestant denominations in which at least 75 percent of respondents said they believed “the Bible is the Word of God”; groups that fall under the 75 percent marker; and nondenominational groupings over or under 75 percent on the same question.

Prior research has suggested that beliefs about the Bible are a good indicator of fertility behaviors in general.

Figure 3 below shows two indicators. First, it details the total fertility rate (TFR)—or number of children born per woman—that a religious group would need to achieve to experience growth, given the conversion rates, and assuming there’s zero immigration into the country.

The second indicator is an estimate of the actual TFR for that demographic, using between-group differences observed in the PRLS in 2014, then applied to actual fertility trends in 2019.

When the needed TFR is higher than the estimated TFR, it means that a religious group is likely to shrink over the next generation—unless it receives new members through immigration.

As the figure above shows, liberal Protestant denominations appear to be facing a dire situation. Given high rates of conversion out of these traditions, they need to achieve fertility rates of 3 children per woman to grow over the next generation. They only have about 1.5 or 1.6.

Conservative Protestants who believe the Bible is the Word of God have higher fertility rates (around 1.8 children per woman) and less-negative conversion rates, meaning they only need to have around 2.4 children per woman.

As a result, liberal denominations can expect a 48 percent decline in a generation, versus just a 26 percent decline for conservative denominations. (Again, that’s assuming no members are gained through immigration.)

On the other hand, there has been robust growth among nondenominational churches. Liberal nondenominational movements have roughly the fertility rate they need for stability (1.8 or 1.9), but conservative nondenominational movements have seen extraordinary growth: They only need to have about 0.8 children per woman to grow, but in fact they have around 1.9.

This means they will more than double in size over the next generation, even without immigrants. Likewise, Pentecostal churches will grow, with actual fertility (2.1) appreciably above needed fertility (1.8).

On the other hand, Catholic and Orthodox churches will see appreciable decline, with an average of 1.9 children born per woman—nowhere near high enough to offset high rates of conversion out of these faiths—yielding a needed fertility rate of 3.1.

Roman Catholic churches can expect a 40 percent decline in the next generation, unless immigration offsets that trend. (Numbers for other faith groups are included in the full brief.)

Although nonreligious fertility rates are very low, high rates of conversion into the “no religious affiliation” category will result in over 50 percent growth in the nonreligious population over the next generation.

In sum, faith groups in America in general face the prospect of stark decline. However, different segments will have different experiences.

For institutionalized Protestantism, Catholicism, and many of the other major world religions, the decline will be swift and deep, with high rates of religious exit and modest-sized families.

Some conservative denominations—for example, the Presbyterian Church in America—will be able to stave off serious decline for the immediate future. But fertility drops will still be the average experience. It’s only within nondenominational Christianity, Pentecostalism, Orthodox Judaism, heterodox offshoots of Christianity, small religious movements, and secularism that we’ll see significant fertility growth.

Takeaways for the church

For reasons I’ve described in length elsewhere, religiosity in America is declining. Changes in education, parenting styles, marital trends, and the geography of American neighborhoods have all conspired to suppress faith across the last several generations.

Meanwhile, the “fertility gap” between religious and nonreligious Americans has been growing for two decades and is now the widest it’s ever been. This fertility advantage, however, is nowhere near large enough to offset losses from the rejection of faith.

To compensate, religious Americans would need to have about 2.4 children each, and in some religious subgroups, even more. Most faith communities in America are having fewer children than they need for long-run stability, and as a result, the next few generations are likely to see a considerable decline in American religion.

However, this decline is not inevitable: Achieving growth again would not require American churches to do impossible things. Having one more child on average, successfully integrating a modest share of immigrants into the US, or achieving higher conversion rates could all stave off decline.

Lyman Stone is a research fellow at the Institute for Family Studies (IFS), chief information officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence, and an adjunct fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Published in collaboration with IFS. The full research brief is available here.