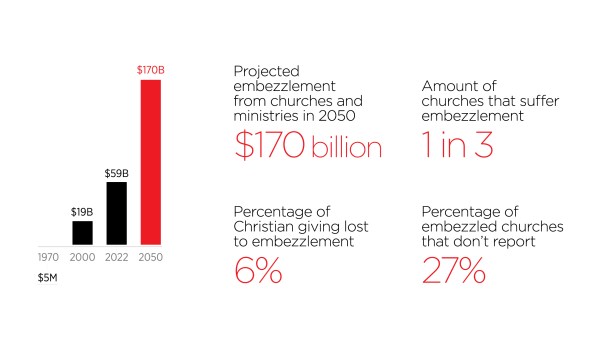

Embezzlement is a growing problem, globally, impacting Christian ministries and churches of every shape and size. The Center for the Study of Global Christianity projects thieves will take $170 billion in the year 2050, if current trends continue, but there are things that individual churches can do to protect themselves.

Recent Cases of Church Embezzlement

1 Oakland, California

A bishop and a lay leader in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church mortgaged properties owned by congregations in Oakland, San Jose, Palo Alto, and Los Angeles to obtain $14 million in high-interest loans. The money was used to buy real estate in North Carolina.

2 Lubbock, Texas

A bookkeeper took $450,000 from Church on the Rock, using the church’s credit cards to pay for a car loan, medical expenses, meals, and to sustain a bakery she co-owned with her daughter.

3 Formosa, Brazil

A Catholic bishop and five priests under his supervision stole the equivalent of $608,000 and used it to buy luxury watches, laptops, cellphones, cattle, a ranch, and even a shop selling lottery tickets. The congregation first noticed the fraud when the reported cost of running a parsonage skyrocketed.

4 Lagos, Nigeria

A church bookkeeper took the equivalent of about $99,000 from Living Faith Church (also known as Winners’ Chapel). When confronted by the pastor, he made a full confession and wrote out an explanation of how he’d stolen the funds.

5 Singapore

The founder and senior pastor of City Harvest church siphoned off the equivalent of $17 million through bogus bond investments. Much of the money was used to support his wife’s music career, which many church members supported as part of a project to use pop music to reach nonbelievers. Church leaders used an additional $19 million to try to hide the embezzlement from auditors.

6 Adelaide, Australia

A woman who worked for a company that collected and deposited money from multiple churches stole about $300,000, which she used for overseas trips and $26,716 in Louis Vuitton products. She was caught when a church finance officer noticed a discrepancy in the reports and started tracking the serial numbers of some donated bills.

Q&A with Todd Johnson, codirector of the The Center for the Study of Global Christianity, on trends in church embezzlement.

Is embezzlement a special problem in churches and Christian ministries?

It is a particular problem with religious organizations because trust is so important. One of the things we found after someone had been convicted of embezzlement, some cases where a pastor was actually in prison, you had church members who still said, “I don’t believe he could do this.” They were the victims, but they still couldn’t accept it.

That shows the power of trust. And trust is good, but if it’s misused—which is the definition of affinity fraud—that’s really a problem.

The Center for the Study of Global Christianity, where you serve as codirector, projects embezzlement in churches in 2025 will be down about $10 billion. Why is that?

I don’t have a single clear answer for that. The projections are composite figures, all tied to gross national income, the demographics of Christianity, rates of Christian income and giving, and the dynamics of fraud. Those are all constantly changing.

It’s almost so complex underneath that it’s hard to ascribe a single reason. These numbers have competing trends within them.

Longer term, the center projects an increase in Christian embezzlement. What is driving that?

It’s going up because of economic growth.

One of the overall trends we see is that Christianity is shifting from more wealthy countries to less wealthy countries. But what complicates that is the leveling out of economic growth, especially in places like India and China.

China was largely rural in the 1990s, and as the church was growing rapidly, it was the church of the poor. Now Christianity has moved into urban centers, and it’s a mixture of rural and urban, and economics are changing, the demographics are changing, and the demographics of Christians are changing all at the same time. But the result is the amount being embezzled is expected to rise there and other, similar places.

We’re also concerned the percentage of fraud will go up because Christianity is growing in places where it’s more independent. That independence is part of the reason Christianity is growing, but that independence also means there’s some likelihood that there are fewer guards in place when it comes to money. So as a global community, we might pay a price for that growth.

There are ways that individual churches can prevent embezzlement. But is there something that could impact the overall rate of fraud?

Even in situations with more controls or more sophisticated structures, people find ways.

We would hope that Christian churches would not have the same percentage of fraud that you’d find in business or other situations. But money is part of Christianity. People make money, they give money. Giving is encouraged in Christianity. And some of that gets stolen. We have an ecclesiastical crime folder here in our office, and it’s getting pretty full.

Our hope in bringing this to light is that churches would take seriously the issues of accountability and stop this as much as possible.

How to Protect Your Church Against Embezzlement

Checks and Balances

Make sure multiple people are involved in every part of the process of handling money. If one person takes the collection, another person should deposit it. If one person pays the bills, another person should reconcile the books. CT’s Church Law & Tax recommends rotating responsibilities on a semiregular basis.

Culture of Accountability

Cultivate a culture that values accountability. Too many Christian ministries rely on trust (and a sense of being “family”), ignoring the fact that we’re all sinners prone to temptation. When Church Law & Tax asked churches that had suffered fraud why they hadn’t instituted systems of accountability, the No. 1 explanation was fear of offending someone. If accountability is seen as offensive, instead of responsible stewardship, churches will be exposed to the risk of embezzlement.

Transparency

Secrecy is good for sin. Honesty encourages moral rectitude. Commit to transparency even when it’s painful. Church Law & Tax found that more than a quarter of churches don’t disclose embezzlement. That is a violation of the trust of donors and concealment of a serious crime.

Daniel Silliman is news editor of Christianity Today.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the denomination of the bishop and lay leader who mortgaged properties church properties in Oakland, San Jose, Palo Alto, and Los Angeles, California. The are African Methodist Episcopal Zion, not African Methodist Episcopal.