Ryan Sullivan didn’t give much thought to his pro-life position as a Christian beyond voting for pro-life politicians. Then he studied Exodus 21:22–24, where God prescribed the death penalty for any Israelite who assaulted a woman and caused her to miscarry.

“In that Scripture, the life inside the womb is treated with the exact same value as the life outside the womb,” said the pastor of Grace Community Church in Jackson, Mississippi. “Once I started thinking that way, I noticed that so much of the world around me—and even the Christian world around me—almost thinks of this abortion issue as merely a political one.”

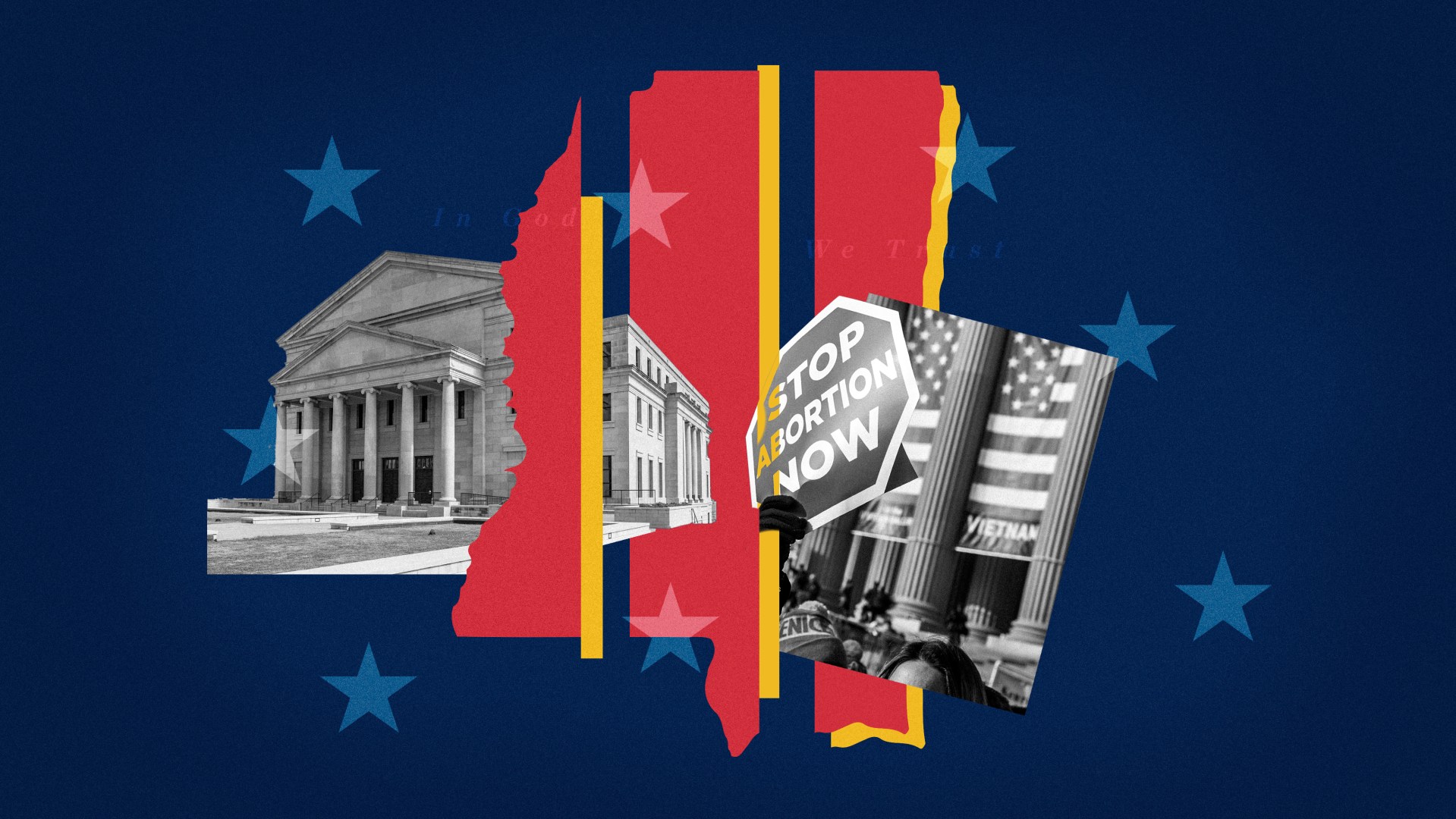

The realization led Sullivan to embrace a new pro-life strategy: pushing local governments to declare themselves “safe” for the unborn. Members of Grace played key roles in establishing several safe cities in Mississippi. To date, 11 cities and two counties in Mississippi, North Carolina, and Alabama have done the same.

According to Les Riley, president of the pro-life Personhood Alliance, the Safe Cities and Counties Initiative shifts the strategic focus from federal-level efforts to overturn Roe v. Wade to local arenas.

Since 1973, the pro-life movement has “built huge organizations, raised millions of dollars, elected pro-life politicians and pro-life majorities, and, at the federal, state, and local levels, we’ve had control of the courts,” Riley said, “yet tens of millions of children are dead.”

The Personhood Alliance decided in 2018 it was time for another approach and started pushing for cities and counties to pass resolutions saying they are safe for the unborn. Other grassroots groups, such as Sanctuary Cities for the Unborn, have advocated ordinances outlawing abortion, to provoke lawsuits that send the question of abortion’s legality back to the courts. Resolutions, on the other hand, are not laws. They send a message that local communities, through their elected officials, “recognize and declare the humanity of the preborn child.”

The resolution template provided by the Personhood Alliance “urges the citizens” in a safe city or county “to encourage the humane treatment of all human beings, including the preborn child, as well as to promote and defend the dignity of all human life.”

A more localized movement made sense to Sullivan: “Why is the state of Mississippi waiting around for a Supreme Court decision to change?”

After connecting with Riley, Sullivan scheduled a meeting with the mayor and several aldermen in Pearl, Mississippi, where he lives. He wasn’t sure how they would respond, but they embraced the idea of a resolution. On October 1, 2019, Pearl became the first “safe city” in Mississippi.

The success inspired one member of Sullivan’s congregation. Christy Wright, a 28-year-old accountant from Crystal Springs, Mississippi, went to the mayor of her hometown and told her about the resolution. In April 2020, Crystal Springs declared itself a safe city for the unborn too. “We all don’t have to do the same thing, but we all have to do something,” Wright said. “If you see a need, meet a need.”

According to the Safe Cities and Counties Initiative, this is the second phase of the plan, after passing local resolutions: The pro-life group wants to activate communities.

Gualberto Garcia Jones, legal counsel and former president of Personhood Alliance, said citizens “take ownership” in Phase 2, which involves educating people and working to create communities that value human life inside and outside the womb. Most communities aren’t ready to outlaw abortion, he said.

“We realized even well-meaning, good-intentioned people have a lot of questions about this and they have a lot of concerns,” Jones said. “You really want to convince your community first that the protection of preborn life with equal protection is a true and good principle they want to invest in.”

The Personhood Alliance argues that the 14th Amendment, passed during Reconstruction to guarantee the rights of citizenship to Black Americans, should disallow legal abortions. The amendment says that no state can “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The unborn should be protected because they are people.

Jones and others pushed for federal legislation to declare that the unborn have the legal rights of personhood in 2004, with little success. They then worked on ballot initiatives in multiple states, including Colorado and Mississippi, but couldn’t win enough votes to change the state constitutions.

In 2014, he and others in the Personhood Alliance decided to focus on “the most local level possible.”

“We’re not reinventing the wheel. The opposite,” he said. “We’re creating a new roadmap.”

So far, no major pro-life organizations have thrown their support behind this new strategy. There is little appetite for inner-movement quarreling, however, so pro-life groups working on state or federal legislation or potential Supreme Court appointments also haven’t directly criticized resolutions or sanctuary-city ordinances.

But pro-life activists see, at the least, limitations to a local-resolutions approach to ending abortion.

Chelsea Patterson Sobolik, policy director at the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, said a “very obvious challenge” is the reality that the Supreme Court legalized abortion across the nation and only some towns in some regions are passing pro-life resolutions.

“It’s not going to be able to happen all over the country,” she said. “So I think that’s why we need all the players at the table, and we need folks in DC working on federal policy. We need state legislatures and folks doing advocacy on a state-based level to ensure that babies are protected all over the country.”

Supporters of the Safe Cities and Counties Initiative say its local focus is important, though, for tackling problems that can’t be dealt with at the state or federal level. For example, Keith Pavlansky, president of Personhood North Carolina and a pastor in Yadkin County, said personhood is fundamentally a “philosophical question” that the local church must be equipped to answer.

“It predates Roe v. Wade,” he said. “The question of when somebody is, or what makes somebody a person, is something that has been asked and answered incorrectly a number of times through human history and, sadly, in the United States of America. We’ve had times like our bout with slavery where the personhood of an entire population was in question based on skin color, which is completely outrageous. It’s not scientific, yet it was the law of the land.”

Sarah Quale, president of Personhood Alliance Education, said she’s passionate about the initiative because it centers pro-life activism in the lives of individual Christians.

“It has to start with us individually, and that means personal repentance,” she said. “We have to focus on being consistent in our own homes, in our marriages, and in our parental responsibilities…that extends to the culture and engaging in relational charity in our own backyard.”

In the past several years, Sullivan has seen that focus shape the culture of Grace Community Church. While several members go to the local abortion clinic every week to pray and ask mothers to consider visiting a local pregnancy clinic, a pharmacist at the church has chosen to only work in places that do not dispense birth control that has the potential to prevent the implantation of a fertilized egg. Others are finding ways to support mothers who’ve decided against abortion, and some are taking care of children.

“It’s just a culture of adopting and fostering children,” Sullivan said. “I praise the Lord for that. I think that’s the Holy Spirit helping people to live out their faith.”

Lanie Anderson is a writer and seminary student in Oxford, Mississippi.