My dad used to sing around the house all the time when I lived at home. He knows about eight bars of every sunny pop song that has been written since the late ’40s. Whatever lyrics he doesn’t know, Dad just makes up on his own. I know some of his made-up songs better than I know the real versions.

Those songs still come to my mind, and sometimes get stuck there, when I turn on the radio or hear a song played in a restaurant or when someone says a phrase or a cliché that happens to also be a lyric. I have to smile when I accidentally sing Dad’s improved version instead of the actual lyric.

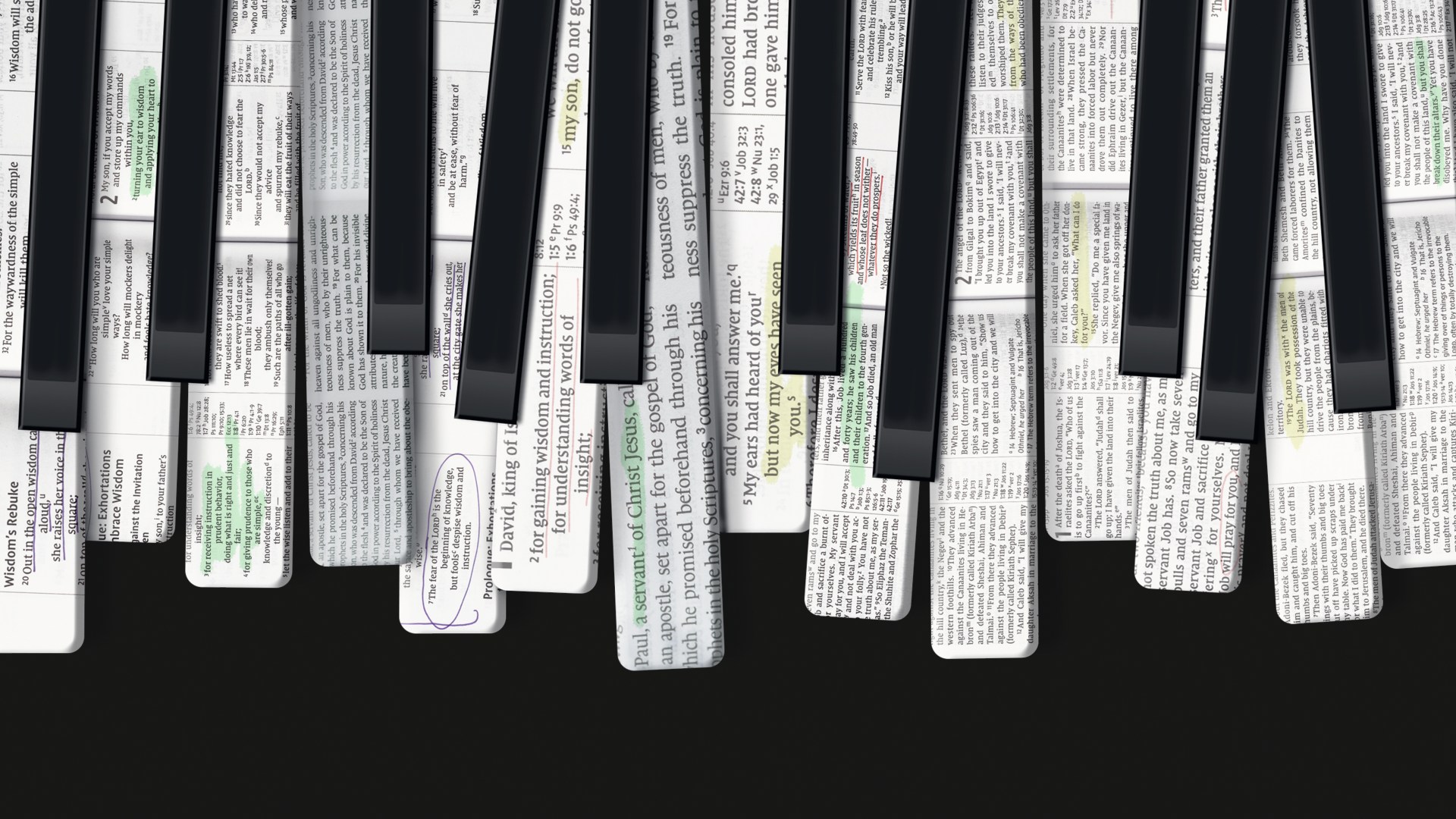

Alongside my dad’s singing, I also memorized a lot of Scripture verses. I wrote them on index cards, studied them at Sunday school, and thought about them during the day. For me, the words of the Bible became like those songs my dad used to sing.

Dad taught me to sing. Mom faithfully taught me Scripture. She invited me to memorize some favorite passages. Now the words are inside me. It’s not surprising, then, when the words of Psalm 103 come to my mind when I see a bald eagle on a trip out West. Or when I stand barefoot on the beach and think of Psalm 139, recalling how the millions of grains of sand are like the number of God’s thoughts. Or when I drive through the mountains and think of Psalm 104:32 when it says that God touches the mountains and they smoke.

Even before we have understanding, we have imagination. When we are young, we talk about imagination. But as adults, we trade imagination for pragmatism. We grow up into more rational, concrete ways of thinking. But in prayer and spiritual formation, imagination is essential for us to grow and move into closer conversation with God.

Scripture brings theology to life, but alongside theological concepts, there is poetry in there too, and dreams and parables and historical records. The words hold together, giving us a better view of God and ourselves and our place in the world.

Learning and memorizing Scripture turned out to be the most important investment I could have made in my early years. I celebrate it now when it’s much harder to learn a language or memorize a Robert Frost poem. These days are full of responsibilities and noisy distractions. These days my mind is less absorbent.

At any age, when we allow Scripture to soak into our hearts, to saturate our roots like the tree in Psalm 1, we are fed by the nourishment of God’s Word. There is nothing more essential to life, even though making the time for it may seem like we’re not being productive.

Inevitably, I think about needing an oil change, or the pile of dishes in the sink, or someone I forgot to call back yesterday, or the mortgage that needs to be paid. Sometimes I keep a to-do list next to my Bible so I can jot down reminders to keep those distractions at bay. Other times, I bring those distractions right into prayer, enfolding my daily tasks in conversation with God’s Spirit.

When we sit with his words, we are creating space to let those words tumble around inside of us. It reminds me of the Fisher-Price Corn Popper push toy that circulates colorful balls when a toddler pushes it around, or a snow globe, filled with white confetti that gets stirred up and circulated when you shake the container.

With God’s words circulating inside of us, we are filled with his life; we are receptive to his Spirit as he activates those words within us, applying truth to the experiences as we move through our days.

Sometimes I have recited Psalm 139 or the Twenty-third Psalm when I couldn’t get to sleep at night—first as a girl, then in stretches of sleeplessness many years later, when the world no longer felt like a place for peace. After years of practicing Scripture to help me sleep, in 2002, I wrote a song called “Now and Then,” an accidental paraphrase.

Stay with me now and then.

From all sides, hem me in,

Sing me a song

so I can close my eyes.

Before I was born,

Every day recorded

Your thoughts like the grains of sand;

Through the wide-eyed nights

And the morning light,

“As thy days demand.”(“Now and Then,” from the album Gypsy Flat Road, 2001)

The last phrase also borrowed a line from the hymn “How Firm a Foundation.” It’s a double reference—I echoed an old hymn as the hymn echoed the Scripture text.

When I took up songwriting as a vocation, Scripture and imagination were the tools I drew upon as I put words to melodies. Hymn lyrics and Scripture phrases spilled through in my songs from the very earliest recordings like “Sunday Morning” (Isa. 44), “Now and Then” (Ps. 139), “Gypsy Flat Road” (Isa. 55), and more and more literally over the years until the present day when I’ve been recently more focused on writing gospel songs meant for church singing. Many of these new songs are intended to help us sing the words right off the page.

Looking back, I can see that the infusion of Scripture into my work is so central and so important. It’s not something that I set out to do in my music, nor is it specialized because I’m a songwriter. Scripture is personal, but it is never private. God’s Word is ours, together. Scripture fills us to the brim and spills over into our daily lives.

Wherever you apply yourself in vocation and work, whether teaching students or working in the finance department, whether caring for children, gardening in your window box, mapping out accounting spreadsheets, or delivering the mail, every kind of work is touched by God’s words.

I remember learning that the Holy Spirit would draw out those words that I had memorized in times when I needed them—when I was out at school, or afraid in the night. It was like planting seeds. Mom helped with memorization, but she trusted that the Holy Spirit would nourish those seeds and make them fruitful in my life.

I went to a public school for elementary grades. Math was not my favorite subject, and I had a teacher in second grade who was intimidating. I was terrified every time I had to walk up to her desk, both because I wasn’t sure of my math skills and because I was anxious about her scolding me for my performance on the material.

I remember the way I would think about Scripture promises when I got scared, mustering up the courage to have the conversation, to walk to her desk. While that was a small thing for a small kid, it was a practice that helped me to grow and that I still draw from today.

My first shared (or publicly offered) song I remember writing was for my eighth-grade graduation. It was the first time I felt the connection between journal writing, a hymn from the hymnal, and a song shared within my school community. Later, I continued to write songs that helped me to process world events, human experiences, and things I experienced firsthand.

My mom brought us every Sunday morning to church where I grew up in St. Louis. She always had tissues in her purse, Tic Tac mints, and Clinique lipstick with the silver-striped case. I remember the Trinity Hymnals all in a row next to the pew Bibles. I would sit with my feet crossed beside her, that hymn book open, poring over the words during all the times of the service when we were sitting down.

I studied the lines on the staff, and I loved the poetry and the way the words moved in rhythmic form. I liked the old words that were not everyday words, like “Though Satan should buffet” and “Here I raise my Ebenezer.” I was curious about what those words meant.

Back at the piano, I sat with my hands on the keys, I made up my own melodies before I could read the notes. I followed the stanzas of these church songs and made them my own.

These old words reminded me that there were stories that came before mine. The hymns convey our emotions, they point to heaven, they enlarge our hope, and they activate our awareness of one another—a useful practice in this age of isolation.

These songs were each like harmonized testimonies of real people seeing God at work in the world—the same world. Standing on the shoulders of the writers before me, and sitting there in that pew beside the old and the young, I took in these same words as they helped me to find my own place in the story.

There’s a visualization of this heritage in the first verse from a song I wrote in 2001, after 9/11, called “Age After Age”:

On the edge of the river, the mighty Mississippi

Two boys spent their summers on the banks by the levee.

When the waters broke and burst the dam,

they were swallowed in a wave of sand.

They pulled the younger one out by the hand

From standing on his brother’s shoulders.(“Age After Age,” from the album Best Laid Plans, 2004)

I’ve been singing this one over many years, and when I first wrote the lyrics, I remembered this story, this heroic image of one boy saving the life of another boy. It helped me to process the immense tragedy of that September.

But this story about the boys came up again recently when someone wrote me an email asking if I knew any historical details of this story, or if it was just folklore. I searched but couldn’t be sure of the answer to his question. He didn’t give up searching for the story, and after a few weeks, he sent me back a stack of digital newspaper clippings dated April 1985.

Timothy Murphy and Darren Ellis were some of five boys playing on sand mounds in St. Louis, near the Mississippi River, when the rain-soaked sand shifted and buried Timothy in a cave-in as he lifted up his friend Darren on his shoulders, saving his life.

Somewhere as a child, I had heard this story, taken it to heart, and even remembered details and descriptions with some of the same words from the news articles that were reflected in the song lyrics. It was no deliberate research, but our hearts have the capacity to imprint story, to hold memory for one another—for a community—and to record these memories for the generations to come.

In the same way, hymns connect us to those who have gone before us, to those whose shoulders we stand upon. From there we can see further and with more clarity than we see on our own. Jesus has held us up on his shoulders, raised us to life by his own death. He is with us when the sand surrounds us, lifting us up to breathe. He lifts us and writes his resurrection song on us, for us to sing when we need it.

Sandra McCracken is a singer-songwriter in Nashville. This article is adapted from her latest book, Send Out Your Light: The Illuminating Power of Scripture and Song (B&H).