Speaking this week on behalf of an Oklahoma death row inmate who claims he did not commit the murder for which he’s served 20 years in prison, pastor T. D. Jakes said, “If Jesus acquitted the guilty, then surely he would advocate for the innocent.”

Jakes is among a group of Christian leaders, including Sojourners’ Jim Wallis, who are advocating for clemency for Julius Jones.

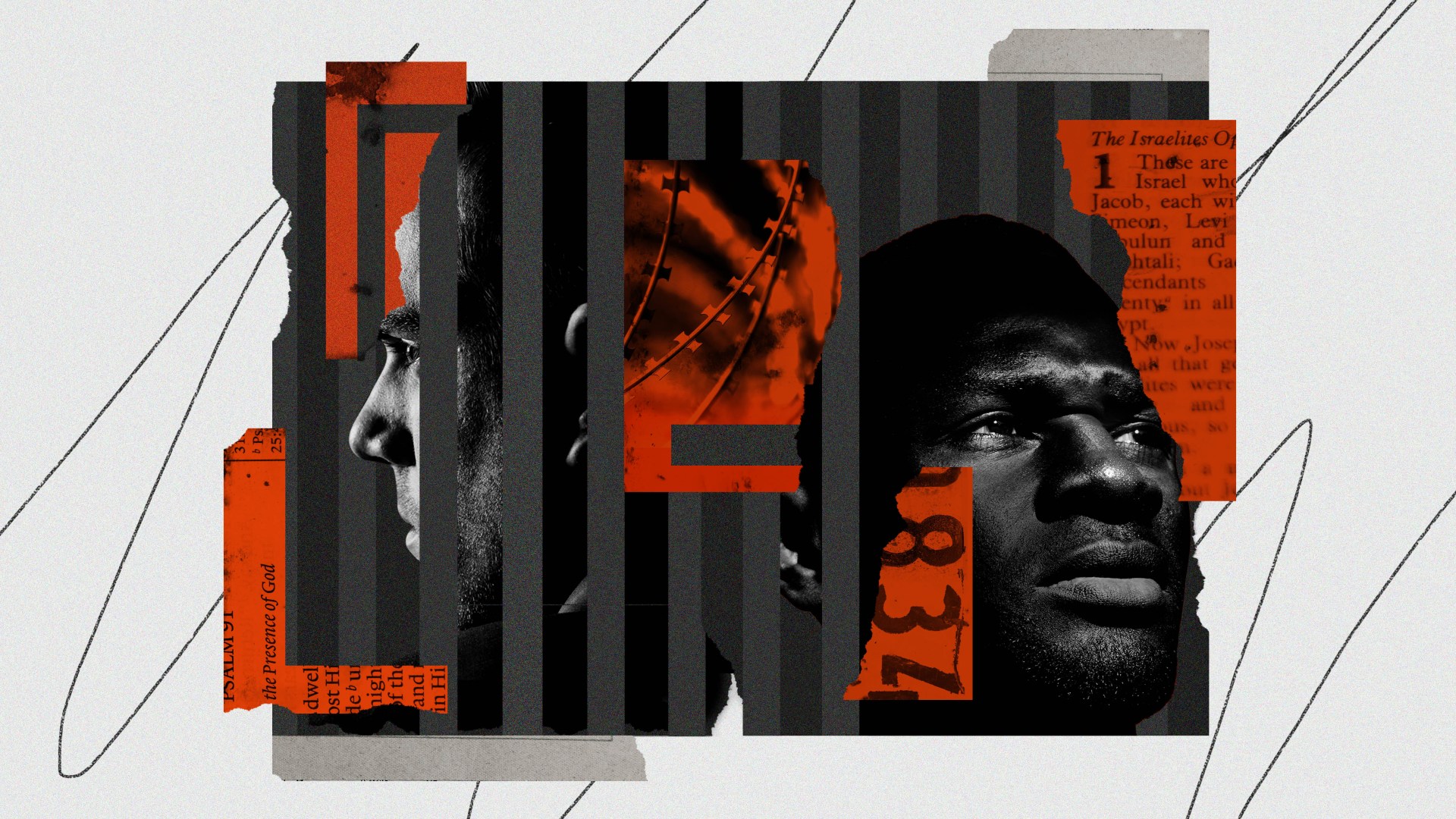

A December study found that both race and views of the Bible may impact how Christians approach mistakes made by the justice system.

White Americans who believe the Bible should be read literally are most likely to see acquitting guilty people as a greater injustice than convicting the innocent, according to sociologists Samuel Perry and Andrew Whitehead, the authors of the study published in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion.

Meanwhile, black Americans, regardless of their view of the Bible, agree that convicting innocent people is the worse of the two mistakes.

A majority of both white evangelicals (59%) and black Protestants (63%) in the General Social Survey—the basis for the recent analysis—were biblical literalists, but the white Americans who held that position were twice as likely as black Americans to prefer wrongful conviction over letting a criminal go free.

Of those surveyed, 21 percent said letting the guilty go free is worse, 64 percent said condemning the innocent, 13 percent couldn’t choose and almost 2 percent did not answer. The justice question, along with the one on biblical literalism, have been asked in four different years of the General Social Survey between 1985-2016. There is no difference over time.

“It was fascinating to us to see how punitive attitudes were so strongly and differently linked to identifying as a biblical literalist,” said Whitehead. “Saying the Bible is the Word of God means something completely different to white Americans than it does to black Americans concerning judicial injustice.”

The findings represent another example of how race influences the ways people apply and practice their faith.

“We can’t just assume that religion ‘works’ the same way for Americans of different racial and ethnic groups,” said Whitehead, explaining that both are closely connected to social boundaries and punitive measures. “Given the history of race and the criminal justice system in the US, it makes sense.”

White and black Americans have different experiences with the justice system. Black Americans represent the majority of the wrongfully convicted, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, which catalogs the cases of innocent defendants.

Other studies have found that those affirming biblical literalism, as well as those in fundamentalist denominations, Republicans, and frequent religious service attenders, would rather convict an innocent person than let a guilty party go unpunished.

New legal efforts attempt to rectify the cruel punishment of a wrongful conviction in a number of states. Last month, Idaho legislators unanimously passed a bill to compensate exonerees for every year spent in prison. The ministry Prison Fellowship advocates for such compensation packages to help the wrongfully convicted rebuild their lives after their release. The group also lays out actions states should take to prevent wrongful convictions, including improving police investigation practices and access to quality DNA testing.

Christian social reformers played a role in the modern prison system from its earliest days. In Colonial America, crimes were dealt with in more of an ad hoc manner—public whipping, hanging, or even the stocks. The Christian intention behind reform was to take a more humanitarian approach: the penitentiary, which was seen as a place where people could become penitent of their sin and learn how to better themselves.

“There are often noble ideas from Christians for dealing with crime … but those proposals—whether the penitentiary system, policing, capital punishment—they routinely cause pain, are difficult and hurt marginalized and disadvantaged communities the most,” said Aaron Griffith, a historian who said these ideas often put “hope in the reforming power of the state in dealing with sin.”

His book, God’s Law and Order, describes white evangelicals’ “predisposition to punitive thinking” and view of crime as a social threat requiring a proactive police response, such as patrolling neighborhoods.

Evangelicals often justify their views with biblical passages like Romans 13 on submitting to government authorities or Leviticus 24:17–21 on requiring “an eye for an eye” as support for a punitive approach to crime.

Referencing Esau McCaulley’s recent book Reading While Black, which addresses policing, Griffith said his reading of Romans 13 is now shaped by the chapter before it. “Paul says that we are to bless those that persecute us, and we are not to repay evil for evil and live at peace with everyone,” he said.

Dominique DuBois Gilliard, the director of racial righteousness and reconciliation for the Evangelical Covenant Church, wrote for CT how the Bible testifies to the evil in human systems, referencing Pharaoh (Exodus 1), Nebuchadnezzar (Daniel 3), and Herod (Matthew 2).

“White evangelicals frequently endorse a blind allegiance to law and order, citing Romans 13:1–7,” Gilliard wrote. “But legal power does not mean ethical power. As subscribers to an Augustinian logic profess, ‘an unjust law is no law at all.’”

The Leviticus passages in proper context aren’t punitive, added Griffith; they’re about trying to set an appropriate response. “It transforms the way we view crimes, like drug crimes,” he said. “What is truly proportional for drug crimes? Is it locking people up because they had weed in their car?”

Five years have passed since the General Social Survey last asked the question about criminal justice. Have views have shifted? Recent data described views of white Catholics and mainline Protestants as growing in awareness of racial injustice within the criminal system.

“White evangelicals have not tracked the same way,” Griffith said. “Overall, it seems to me even as the rest of the country is changing on this, evangelicals are still lagging behind.”