We didn’t know anything about critical race theory. Or implicit bias. There was no elaborate argument for centering minority voices. But as a group of 20-somethings from an almost-all-white suburb about to plant a church in the former capital of the Confederacy, we were thinking a lot of racism, reading the Scripture, and praying.

And something happened. On the basis of simple Christian beliefs—the sort every follower of Jesus would affirm—our new church saw the benefit of hearing black voices and learning from black sources.

To begin with, the Scriptures are clear that while truth is objective, every knower is inescapably subjective. We are warned that our inherent limitations are fraught with self-deception (Jer. 17:9; Ps. 19:12–13)—a deception so deep that it often manifests long after we have received the restorative gift of the Holy Spirit (Gal. 2:11–14). In other words, one of the fundamental problems we face isn’t simply that we are ignorant of important subjects that we ought to know but that we have sinfully misguided assumptions and prejudices that we aren’t even aware of. This is particularly concerning for those who have been called to preach the truth!

Yet C. S. Lewis would remind us that, while we all have blind spots, we do not all have the same blind spots. So diversity helps us correct our self-deception. All the more reason to obey the command we received through the apostle James: “My dear brothers and sisters, take note of this: Everyone should be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry” (James 1:19).

At the start of Remnant Church, my fellow pastors and I were thinking about that old truth that those who are called are not necessarily equipped. We realized that to plant this church, we needed an education in the firsthand experience and self-understanding of African Americans, who are the largest racial minority in our context. They are also a people group whose history is disproportionately filled with suffering injustices while still embracing the Christian faith at the highest rates.

For all these reasons, we decided at the beginning that we needed to hear black voices.

Learning from others

The sheer number of resources to choose from is overwhelming (and it has only grown since we began). In God’s providence, however, we stumbled upon the writings of Carl Ellis Jr.

Ellis is a conservative black theologian who was active during the civil rights movement—a tragically rare but exceedingly beautiful combination. Not long after reading his book Free at Last?: The Gospel in the African American Experience, a few of us traveled to Mississippi for a seminar with him on race and the gospel.

We left Ellis’s course with a massive list of recommended reading and a lifetime of ministerial insights, including one that has proven helpful many times over: You have to know something about the past if you want to understand problems of the present.

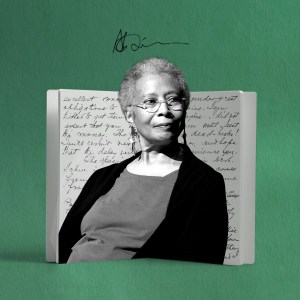

We started reading early black activists like Frederick Douglass, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Francis Grimké; black historian Isabel Wilkerson and religious sociologist C. Eric Lincoln; the poet Langston Hughes and novelist Alice Walker; and the biographies of civil rights activists like Malcolm X, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Martin Luther King Jr., whose sermons and essays we read with great interest.

WikiMedia Commons / Illustration by Mallory Rentsch

WikiMedia Commons / Illustration by Mallory RentschSimilarly, we started reading and listening to sermons from black preachers like Francis Grimké, Gardner C. Taylor, E. K. Bailey, and Tom Skinner, who provided invaluable examples of how the one Word of God can be applied in many different ways. On top of all this, we attended black-led conferences and had many conversations with brothers and sisters who graciously shared their stories and patiently answered our questions.

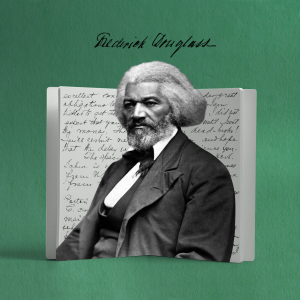

Then we turned to some especially more controversial voices. Indeed, this seemed essential after reading Eugene Robinson’s book Disintegration, which argues that it’s increasingly impossible to speak of a monolithic “black experience” in America today. For this reason, we read works by socialist philosopher Cornel West and black liberation theologian James Cone. We read younger black thinkers, like Coleman Hughes and Thomas Chatterton Williams, who call for postracial societies. We read black conservatives like Thomas Sowell and Shelby Steele, who challenge prevailing assumptions about race and class. And we read critical works like Anthony Bradley’s Liberating Black Theology and Thabiti Anyabwile’s The Decline of African American Theology, which offer important reminders that no faith tradition is free from error or above critique.

Jamie McCarthy / Getty / Illustration by Mallory Rentsch

Jamie McCarthy / Getty / Illustration by Mallory RentschMaybe it goes without saying, but the people we read and listened to didn’t all agree on everything. On vital points, their diagnoses differed and their prescriptions conflicted. Some of the people we sought to learn from even espoused ideas that directly conflict with our understanding of the essential truths of “the faith that was once for all entrusted to God’s holy people” (Jude 3). Nevertheless, for the same reasons the apostle Paul made himself familiar with pagan authors (Acts 17:28), we found it helpful to be aware of multiple voices in the conversation so that we might obtain a more accurate, nuanced, and sympathetic understanding.

Start with charity

As we continued to read, a thorny challenge emerged: How could we be “quick to listen” without becoming uncritically accepting of every new idea? Or again, how could we judge between the claims of those who led similar lives but landed in contradictory places without simply scratching an itch to discover what we biasedly wanted to hear (2 Tim. 4:3)?

As we continued reading, we discovered two guiding principles for majority-culture people engaging minority-culture perspectives. First, when it comes to someone’s personal narrative or lived experience, the starting point should be a charitable benefit of the doubt, not a critical posture of skepticism. That goes double for minority authors who profess our common Lord. Second, the consensus of the Christian tradition is deep and trustworthy.

WikiMedia Commons / Illustration by Mallory Rentsch

WikiMedia Commons / Illustration by Mallory RentschIt is important to remember that Christianity long predates injustices like the Atlantic slave trade and its system of self-serving justifications and institution-reinforcing prejudices. Moreover, early Christian theologians like Augustine, Athanasius, and Mark the Evangelist remind us that Africa shaped the Christian mind. In other words, Christianity has never been an exclusively European faith. We can confidently reject the “colonizer’s religion” and still cling to “the faith that was once for all entrusted to God’ holy people” (Jude 3). It includes, after all, many saints who were enslaved (1 Cor. 7:21) when they received the same faith in which we stand (1 Cor. 15:1–4).

We didn’t announce to the congregation that we were studying materials to address our blind spots and broaden our perspectives. Nor did we immediately start a group study or sermon series on race (though we did, of course, address the subject many times).

We didn’t want to do the work to win credit. We trusted, instead, that the broadening of our perspectives (and correction of our biases) would show, and that would lead naturally to the church’s spiritual growth.

Which is what happened. When we really changed by all of our reading and listening, we had new ways of seeing the needs in our community, new ways of seeing the same Scriptures, and new ways of speaking about what we saw. The more we studied and listened, the more natural it became to talk about race without feeling self-conscious or defensive. As pastors, we became more adept at applying the biblical texts to our context. Isn’t that what every pastor hopes to do?

The only lasting solution

With apologies to the apostle, it is not that we have already arrived at our goal or attained perfection in this area. We’re still learning. We’re still growing. And we’re still making mistakes. Yet perhaps that’s why, immediately after Paul declares, “There is no Gentile or Jew, circumcised or uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave or free, but Christ is … in all” (Col. 3:11), he tells us to put on “compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness and patience. Bear with each other and forgive one another if any of you has a grievance against someone. Forgive as the Lord forgave you” (vv. 12–13).

It would seem that Paul knew then what the American church is just slowly and painfully discovering now. Practicing the unity that we have in principle (Eph. 2:11–21; Rom. 15:1–7) is a difficult endeavor for sinful people. It takes effort to embrace and embody this gift (1 Cor. 15:10). But as civil rights activist and evangelical icon John M. Perkins said, the only lasting solution to ethnic strife is the gospel proclaimed by “intentionally multiethnic and multicultural churches [that] bust through the chaos and confusion of the present moment and redirect our gaze to the revolutionary gospel of reconciliation.”

These words are no longer theoretical for us. And we thank God for how he has blessed our church’s endeavors toward this end, with people of color serving at every level of leadership in our once-homogenous church. We have sought to be the kind of community who so deeply believes the good news that God has united us in principle that we are committed to embodying that unity in practice.

Lord, may it ever be so.

Doug Ponder is a teaching pastor at Remnant Church in Richmond, VA, where he lives with his wife, Jessica, and their four sons. He also serves as the Professor of Biblical Studies at Grimké Seminary and its School of Urban Ministry.