The data didn’t make sense.

The American Bible Society (ABS) and Barna Group researchers looked at the results from 1,000 cellphone interviews asking people about their engagement with Scripture. The numbers seemed to show more people were reading the Bible—a lot more. But nothing else had dramatically changed.

There were not more people praying, or going to church, or identifying religion as something important in their lives. There wasn’t a corresponding increase in people saying the Bible was the Word of God. It was just this one metric, breaking logic and defying trends.

“When you get a big surprise in the social sciences, that’s often not a good thing,” said John Farquhar Plake, lead researcher for the State of the Bible 2020. “We were seeing from the cellphone responses what we considered to be an unbelievable level of Bible engagement. You think, ‘That might be noise rather than signal.’”

Researchers found the cause of the “noise” when they compared the cellphone results with the results of their online survey: social desirability bias. According to studies of polling methods, people answer questions differently when they’re speaking to another human. It turns out that sometimes people overstate their Bible reading if they suspect the people on the other end of the call will think more highly of them if they engaged the Scriptures more. Sometimes, they overstate it a lot.

The ABS and Barna decided to do 3,000 more online surveys and then throw out the data from the phone poll. For the first time, the annual State of the Bible study was being produced using only online survey data.

Christian groups are not the only ones changing the way they measure religion in America. Pew, considered the gold standard for religious polling, has stopped doing phone surveys.

Greg Smith, Pew’s associate director of religion research, said Pew asked its last question about religion over the phone in July 2020. It may do phone surveys again someday, but for the foreseeable future, Pew will depend on panels of more than 13,000 Americans who have agreed to fill out online surveys once or twice per month.

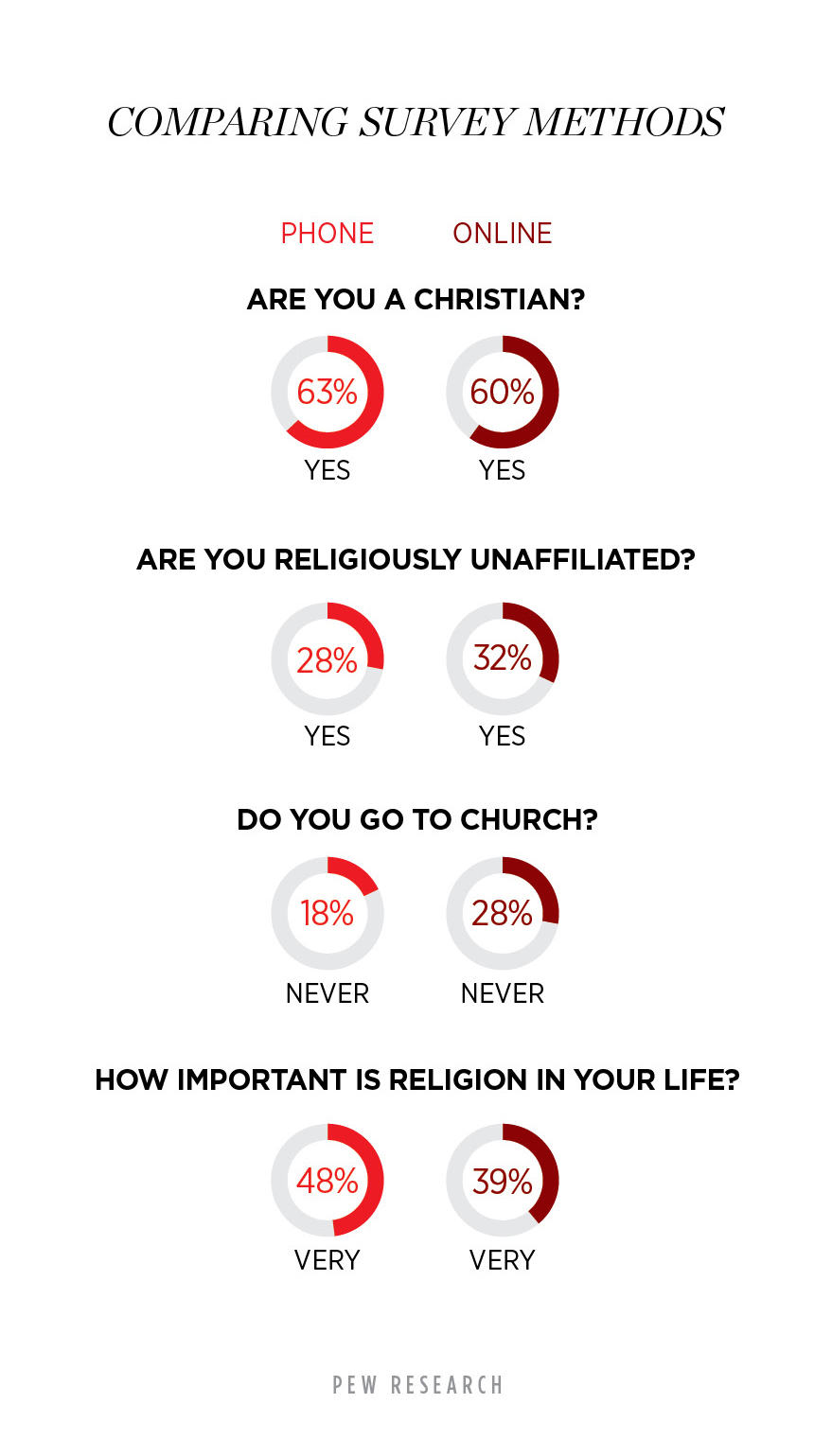

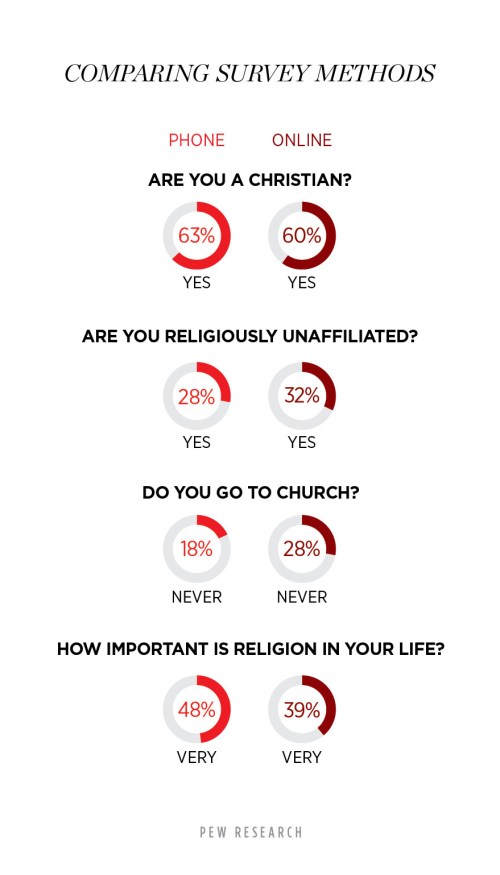

Smith said that when Pew first launched the trend panel in 2014, there was no major difference between answers about religion online and over the telephone. But over time, he saw a growing split. Even when questions were worded exactly the same online and on the phone, Americans answered differently on the phone. When speaking to a human being, for example, they were much more likely to say they were religious. Online, more people were more comfortable saying they didn’t go to any kind of religious service or listing their religious affiliation as “none.”

“Over time, it became very clear,” Smith said. “I could see it. I wasn’t doing research on ‘mode effects,’ trying to see how different modes of asking questions affect answers. I could just see it.”

After re-weighting the online data set with better information about the American population from its National Public Opinion Reference Survey, Pew has decided to stop phone polling and rely completely on the online panels.

This is a significant development in the social science methodology Americans have relied on to understand contemporary religion. How significant remains to be seen.

Modern polling began in 1935, when journalism professor George Gallup used sampling techniques to correctly predict the results of the presidential election and then made a business out of it. From the start, Gallup focused on questions about politics, but he also asked Americans about their religious beliefs and practices. One early survey found that about a quarter of people had read the Bible all the way through, and 46 percent of those people concluded they preferred the New Testament while 19 percent preferred the Old.

Polling increased after World War II, when more Americans got phones. By the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, polls became the dominant way that Americans understood religion in the US.

For Christians who wanted to preach the Good News, start churches, and encourage people to study the Bible, polls seemed like an invaluable resource. If you want to love your neighbors, it helps to know who they are. More generally, Americans felt this was the best way to move beyond impression and anecdote and get an accurate picture of faith in the country.

Some critics have contended that the dependence on polls led to deep misunderstandings, however. Sociologist Robert Wuthnow has argued, for example, that pollsters created “white evangelicals” as a category in the 1970s, erasing a lot of differences and distinctions. If they had decided that regional variation or theological particulars mattered more, or race less, then “evangelicals” would be thought of differently today.

Similarly, Wuthnow argued that polls have always inflated church attendance, although the social desirability bias only became visible with the gradual change in polling methodology.

“At best,” he wrote in Inventing American Religion, “polling information about attendance provided crude indication of religious involvement.”

Pew’s analysis finds that, today, about 10 percent of Americans will say they go to church regularly if asked by a human but will say that they don’t if asked online. Social scientists and pollsters cannot say for sure whether that social desirability bias has increased, decreased, or stayed the same since Gallup first started asking religious questions 86 years ago.

“My own sense, having been in the field 20 years now and reading the literature, is that that source of error and type of bias is quite consistent and quite robust,” said Courtney Kennedy, Pew’s director of survey research. “With religion, it’s so personal and nuanced, we may never know a true score about whether or not you prayed or believe in God.”

While pollsters attempt to eliminate or at least reduce social desirability bias, however, some scholars say the “error” in the data is actually meaningful and should be studied. At the University of Massachusetts Boston, sociologist Philip Brenner gathers small groups of people, asks them questions about things like church attendance, and then asks them why they answered the way they did.

“When we hear ‘error,’ we think accident, like random chance,” Brenner said. “But these aren’t accidents. These have motive behind them. The respondents are telling us something about themselves: who they are, who they want to be, who they think they ought to be. That may not be the information we wanted, but it’s still useful if we can understand what they are saying.”

Brenner thinks there should be more emphasis on interpretation. Data that seems “bad” could make sense, he argues, if more time and effort were put into parsing the human motivations behind seemingly false statements like “I read the Bible every day.”

But the promise of polling is something simpler. The goal is hard numbers quantifying religious activity. Polling firms want to know how many Americans really do read the Bible every day. Pew, Barna, and the American Bible Society are refining their methods and moving from phone polls to online polls in the hopes that they can achieve an accurate—if never perfect—picture of American faith.

When the data does make sense, according to the ABS, it reveals something powerful. “We can see from the data that when people read the Bible, they really do change,” Plake said. “We want you to understand, we’re seeing God at work in people’s lives, and it shows up in the data.”

Daniel Silliman is news editor for Christianity Today.