Recently, a friend asked on Twitter if the Bible passes the Bechdel-Wallace test. Although this question has been asked on the internet before, my friend’s tweet made me wonder if I could use my Bible programming skills to do a deeper data-drive analysis than what I found online. (One of the best iterations comes from a blogger priest named Paidiske.)

If you’re not familiar with it, the Bechdel test “is a measure of the representation of women” in movies and books. It’s based on a comic by Alison Bechdel that suggests a work must contain a scene that meets three specific criteria: (1) at least two named women who (2) talk to each other (3) about something other than a man.

The films in the Star Wars franchise can serve as an example of the test’s usefulness. The first Star Wars movie was praised for presenting a strong female character in Princess Leia. However, the only other named female character in the movie is Aunt Beru, but she and Leia never meet or talk, so the film fails the Bechdel test. By contrast, The Force Awakens (episode VII) includes a scene in which Rey and Maz Kanata discuss Rey’s destiny, which passes all three elements of the Bechdel test.

The Bible certainly doesn’t need to pass the Bechdel test in order to be God’s Word. That would probably be a bad example of presentism. But the test can still be a useful way of reexamining the biblical stories and seeing God’s care for all image bearers.

Part of my interest in this question comes from the fact that I like playing with Bible data. But the deeper reason is that I am married to an incredible woman whose depths I have only just begun to see over the last 15 years, and I am father to an indescribably interesting young woman who wants to know: What is the place and value of women in the world? And what does the Bible have to say about that question?

The Bible as Data

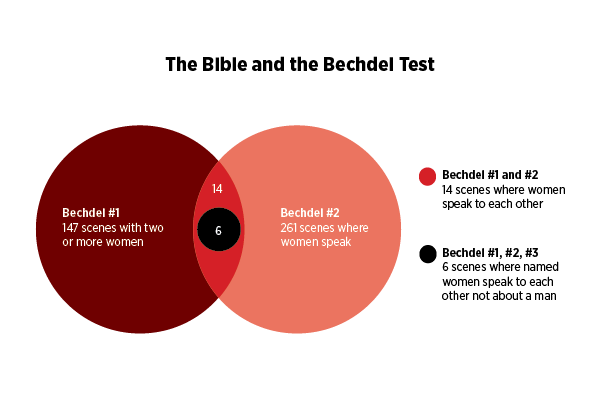

To explore the Bechdel test question, I used an incredible open source dataset created by Robert Rouse of viz.bible that includes people, places, and events in the Bible. I used his data to find all the passages where women are mentioned together (Bechdel test number 1) and all the passages where women speak (Bechdel test number 2). Then I examined the overlaps to find which ones fully passed the test (including Bechdel test number 3) and which ones partially passed for various reasons. (My full data report is available on my blog.)

Here’s a summary of what I found. Rouse’s database has 3,070 characters, and 202 of those are women. (For comparison’s sake, the Quran has one named woman, Mary, and other religious texts like the Bhagavad Gita have none.) Of the 66 books in the Protestant canon, 34 are narrative or mostly narrative books, and 41 have female characters.

Narrowing to the pericope level, there are 147 scenes with two or more women (Bechdel test 1), 261 scenes where women speak (Bechdel test 2), and 14 where women are speaking to each other (Bechdel test 3).

Bechdel and Beyond

So does the Bible pass the Bechdel test?

This short answer is yes; there are multiple scenes where two named women have a conversation not about a man.

The longer answer is more complex but also richer, I think. Although there are fewer female characters in the Bible than male characters and very few scenes that unambiguously pass the Bechdel test, when we read female-centric passages carefully, we find that the Bechdel test alone doesn’t tell the full story. Whereas men are gallivanting all over the pages of Scripture, faithful women are always present and prominent during the key movements of the biblical story when God is making major moves toward saving humanity. It’s almost as if, in a world of patriarchy and misogyny, the presence of women functions as a marker that says, “Pay attention; this is important!” for each major movement of the biblical story.

The Beginning

Genesis begins by reminding readers that both “male and female” are created in God’s image (1:27). Then in Genesis 3, Eve speaks to the serpent (v. 2) and to God (v. 13) on equal footing with Adam. Although these scenes don’t pass the Bechdel test, my friend and colleague Sandra Glahn suggests that a new test is needed where “a named woman having a conversation with a being that outranks a man about something other than a man gets extra points in the representation scale.”

As we read on, we find that the rest of Genesis can be a brutal place, especially for women, who are often exploited, sexualized, and mistreated by men or one another. Genesis also contains the launch of God’s plan to redeem humanity through a single human family, and in that story comes a powerful scene that derives some of its significance precisely because it doesn’t meet the Bechdel test.

In Genesis 12, God promises that he will make the descendants of Abram and his wife, Sarai (both named in Genesis 11:29), into a great nation, through whom he will bless all people groups. Sadly, Abram and Sarai fail to trust that God can give them a child, and in the process, they abuse Sarai’s servant Hagar. Sarai and Hagar’s dialogue is not recorded, but we can fairly well infer that the conversation was quite nasty.

However, the words of Hagar that are recorded make her the first character in Scripture to give God a name. “She gave this name to the Lord who spoke to her: ‘You are the God who sees me,’ for she said, ‘I have now seen the One who sees me’” (Gen. 16:13).

This is one of the first instances where not passing the Bechdel test is precisely what gives the scene its power. In the midst of a woman’s suffering, God sees her pain and is working to redeem it.

As we continue through the early biblical story, we encounter passages that fail the Bechdel test because they pass only the third criterion, where named women speak about something other than men, but they speak to men or crowds rather than to other women. For example, in the story of Moses’ birth, Pharaoh’s daughter is unnamed, so her conversation with Miriam doesn’t fully pass the Bechdel test (Ex. 2:1–10). Other key instances come with the female negotiators in Numbers 27 (see also Joshua 17) and in Deborah’s song in Judges 5.

Judges 4 and 5 contain the stories of Jael and Deborah, and although the two characters never meet or speak, they represent women as whole persons, capable of being wives and mothers but also leaders, negotiators, prophets, and stone-cold assassins.

The Blessing Is Passed (Along with the Bechdel Test)

The next major movement of the biblical story comes in the establishment of the Davidic covenant and the promise of a righteous king whose just reign will be eternal. This major event is preceded by and dependent upon the clearest case of the Bible passing all three elements of the Bechdel test.

In the opening chapters of Ruth, Naomi, Orpah, and Ruth discuss men: their dead husbands and the prospect of future marriage, and Boaz. But Naomi and Ruth also talk to one another about their lives, their relationships to each other, and their work (Ruth 2:2). In the middle of these conversations comes one of the most beautiful passages in all of Scripture—one that conveys the promise of God’s chosen people bringing the good news to all nations. That story is told through an exchange between two widows, both foreigners and immigrants:

But Ruth replied, “Don’t urge me to leave you or to turn back from you. Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay. Your people will be my people and your God my God. Where you die I will die, and there I will be buried. May the Lord deal with me, be it ever so severely, if even death separates you and me.” When Naomi realized that Ruth was determined to go with her, she stopped urging her. (1:17–18)

The highpoint of Ruth stands out even more sandwiched between the brutality of Judges and the books of Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles. In these books, women are rarely recorded speaking to one another (1 Sam. 25:18–19), but women do speak, and one scene in particular stands out.

In 2 Kings 22, we meet King Josiah, who ascends to the throne at age eight. Eighteen years later, he decides to clean up the temple, and in the process, one of the priests famously recovers “the Book of the Law” (v. 8). After being broken by hearing the words of Scripture for the first time, Josiah doesn’t consult the priests. He instead asks five male priests to seek the wisdom of Huldah the prophetess.

This is another instance in which not passing the Bechdel test heightens the significance of the story:

Hilkiah the priest, Ahikam, Akbor, Shaphan and Asaiah went to speak to the prophet Huldah, who was the wife of Shallum son of Tikvah, the son of Harhas, keeper of the wardrobe. … She said to them, … “Tell the king of Judah, who sent you to inquire of the Lord, ‘This is what the Lord, the God of Israel, says concerning the words you heard: Because your heart was responsive and you humbled yourself before the Lord … I also have heard you.’” (vv. 14, 18–19)

According to Aimee Byrd, “It’s the first time we see the Word of God being authoritatively authenticated as canon, and it’s done by a woman. That’s amazing.”

The Savior Arrives

In the Gospels, some passages—like Martha telling Mary that Jesus wants to see her (John 11:28)—clearly fail the Bechdel test. But some of the most significant scenes actually pass it.

The Incarnation itself is marked by a scene that passes the Bechdel test: Elizabeth and Mary’s discussion of their upcoming pregnancies (Luke 1:41–45). In the following chapter, when baby Jesus is brought to the temple, he meets Simeon and then Anna. After seeing Jesus, Anna is recorded as being one of the first to explain the theological significance of this little baby. Arguably, the scene partially passes the Bechdel test because a named woman is speaking to people (presumably other women) about the redemption of Jerusalem:

There was also a prophet, Anna, the daughter of Penuel, of the tribe of Asher. … Coming up to them at that very moment, she gave thanks to God and spoke about the child to all who were looking forward to the redemption of Jerusalem. (2:36, 38)

Moving forward to Jesus’ death, we find a scene in which Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome discuss the stone being rolled away. The stone is of course related to Jesus, but it is striking that in the most significant event in human history, named women are talking to one another about a major plot point:

Very early on the first day of the week, just after sunrise, they were on their way to the tomb and they asked each other, “Who will roll the stone away from the entrance of the tomb?” (Mark 16:2–3)

And finally, in a scene that fails the Bechdel test but is significant because of it, Mary Magdalene becomes the first to share the good news that Jesus has risen from the dead:

Mary Magdalene went to the disciples with the news: “I have seen the Lord!” And she told them that he had said these things to her. (John 20:18; see also Luke 24:10)

It is a wonder that the birth, death, and resurrection of Jesus and the proclamation of His triumph are tied to scenes that pass (or intentionally fail) the Bechdel test.

The Early Church

The book of Acts tells the story of the spread of the church, but it does not record women directly dialoguing with one another. And yet there are stories of women taking significant roles, such as Lydia lending her home to one of the earliest churches (Acts 16:11–15) and Priscilla and her husband Aquila team-teaching theology courses for Apollos (18:26).

My algorithm also surfaced two instances of named women speaking (“greeting”) at the end of Paul’s letters:

The churches in the province of Asia send you greetings. Aquila and Priscilla greet you warmly in the Lord, and so does the church that meets at their house. (1 Cor. 16:19)

Greet Priscilla and Aquila and the household of Onesiphorus. … Eubulus greets you, and so do Pudens, Linus, Claudia and all the brothers and sisters. (2 Tim. 4:19, 21)

Claudia, named in the Timothy passage, is thought to be a British woman living in Rome and among those who cared for Paul during his imprisonment. Without dialogue or named characters receiving the greetings, these verses don’t pass the Bechdel test, but they do highlight (again) the significant roles that women played in the early church.

There is one more passage worth pointing out that arguably includes two significant female characters. In Paul’s first letter to Timothy, he pens some of the most controversial words about men ( 2:8) and women (vv. 9–12) in all of Scripture, and then he follows with this:

For Adam was formed first, then Eve. And Adam was not the one deceived; it was the woman who was deceived and became a sinner. But women will be saved through childbearing—if they continue in faith, love and holiness with propriety. (vv. 13–15)

Although most modern English translations render this passage similarly, it is important to point out that the plural word “women” in verse 15 is not actually in the Greek, nor is the punctuation between verses. The verb “will be saved” is singular (see the English Standard Version), which means it should be connected to the last person in the passage.

In addition, the word for “childbearing” is not used anywhere else in the New Testament, and its grammar indicates that it might not be referring to childbearing generally but to a specific childbearing. Citing some church fathers and several modern commentators, George Knight writes, “The most likely understanding of this verse is that it refers to spiritual salvation through the birth of the Messiah.” This means the passage should be rendered, “But she [Eve] will be saved by [Mary’s] childbearing” (v. 15).

Although Eve was the first to become a sinner, by God’s grace, the vessel through which deception came into the world is the same vessel through which redemption will come. Eve, like all of us, will ultimately be saved by the work of Jesus, which began with a single cell in Mary’s womb.

Although many commentators reject this interpretation (see the New English Translation notes), I prefer it for two reasons. First, it avoids the problem of explaining how childbearing confers salvation. More importantly, it offers one of the most sweeping, beautiful, and succinct retellings of the entire biblical story and reminds us how God is saving all humanity, male and female, from beginning to end, by displaying his infinite power and love in the most vulnerable and intimate of ways.

Scripture, I would argue, passes the Bechdel test and also goes way beyond it. In this final scene of two women together, they are valued not for what they say or what they do but for who they are: children of God. Whatever the state of our current conflicts over ethnicity, gender, power, and economics, from the first sinner to the last, one day, we all will be saved by God the Son who became a man carried by a woman.

Let us then continue in faith, love, and holiness.

John Dyer (PhD, Durham University) is a dean and professor at Dallas Theological Seminary who teaches and writes on theology, technology, and sociology. You can follow him on twitter @johndyer and find him on his blog. This essay was adapted from a blog.