In this series

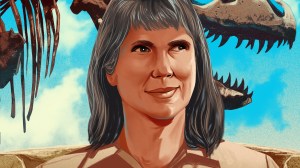

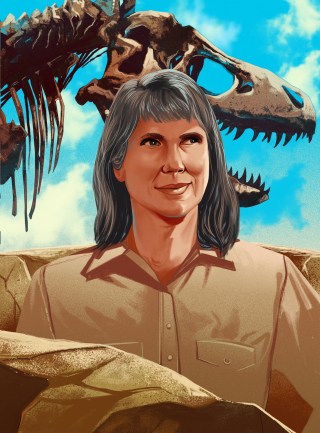

Paleontologist & molecular biologist, Raleigh, North Carolina

Mary Schweitzer’s career has faced scrutiny since the beginning, and the whole thing was accidental, she said. After working other jobs, she pursued an interest in medicine while balancing the responsibilities of motherhood. But on a whim, she audited the class of Jack Horner, the paleontologist who advised the Jurassic Park movies. Fascinated, she switched paths and began her PhD, helping with a Tyrannosaurus rex that Horner found in 1992.

Her old medical interests immediately affected the trajectory of her newfound career.

“I kept smelling something very odd” in the dinosaur bones, she recalled. It reminded her of smells in the campus cadaver labs. Most paleontologists came from a geology background, so “it didn’t dawn on them that it smelled,” she said. “Nothing has an odor unless it has organics associated with it.”

She analyzed the bone and found blood vessels, cells, and collagen inside—evidence of living tissue inside dinosaur bones millions of years old. “To put it mildly, my thesis was not well accepted in the grander community,” she said.

In 2000, another T. rex was discovered and she attempted to repeat the analysis, the results of which were published in Science in 2005.

“Since then, we’ve tried really hard to replicate it and provide chemical data,” said Schweitzer, who is now at North Carolina State University. Her lab has expanded to other specimen and tissue types, and a lab in Sweden has replicated her findings in a sample from another dig.

“I’m not doing what I do for attention,” she said. “I’m utterly fascinated by the world God made, so I just try to ignore what other people say and just do the work in a way that God’s blessed me to do.”

When Schweitzer started, there were maybe four women in the field, she said. Now there are as many up-and-coming women in paleontology as men, and most of them have a biology background like herself.

In her observation, women spend less time in the field than men, partly due to family commitments. But it’s allowed many women to ask questions around what they can analyze in the lab. “It affects the questions we ask and how we address those questions, and I think it makes the whole field a lot stronger,” she said.