The rapid evolution of religiosity in the United States is by now a familiar story. The decline of American Christianity “continues at a rapid pace,” Pew Research reports, while the religiously unaffiliated, or “nones,” grew from 16 to 26 percent of the country from 2007 to 2019 alone. Evangelical churches are retaining more members than their mainline counterparts, but evangelicalism too is losing cultural cachet and overall population share.

Yet we would be mistaken to conclude Americans are becoming less religious. We live in a secular age, as philosopher Charles Taylor famously argued, not because we have lost our human instinct to worship but because the object of our worship is no longer assumed. We have options. We can seek meaning, purpose, and community outside the church and institutional religion altogether, and increasingly so, as Tara Isabella Burton details in her forthcoming Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World (Hachette, June 16, 2020).

“We do not live in a godless world,” Burton argues in subversion of her own subtitle. “Rather, we live in a profoundly anti-institutional one, where the proliferation of internet creative culture and consumer capitalism have rendered us all simultaneously parishioner, high priest, and deity.” Armed with a doctorate in theology from Oxford and a journalist’s eye for anthropological curiosities, Burton delves into self-focused “new religions” as disparate as SoulCycle and Harry Potter.

What odd creatures people are, I kept thinking while reading, confident in my own strength to resist such alien liturgies. Yet there’s a more insidious temptation in what Burton dubs “remixed” religion, a siren song away from Christ that—unlike fixation on wellness culture or Hogwarts fan fiction—isn’t as easy to identify as a superficial contender for our souls. That age-old lure is politics and its consuming pursuit of power, demanding an allegiance from us we owe only to God.

“You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them,” Jesus warned his disciples when the sons of Zebedee sought seats of honor at his right hand and his left. “It will not be so among you,” he charged, “but whoever wishes to be great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be your slave; just as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many” (Matt. 20:20–28, NRSV).

This call call to humility, service, and even self-abnegation… goes against our every fallen instinct.

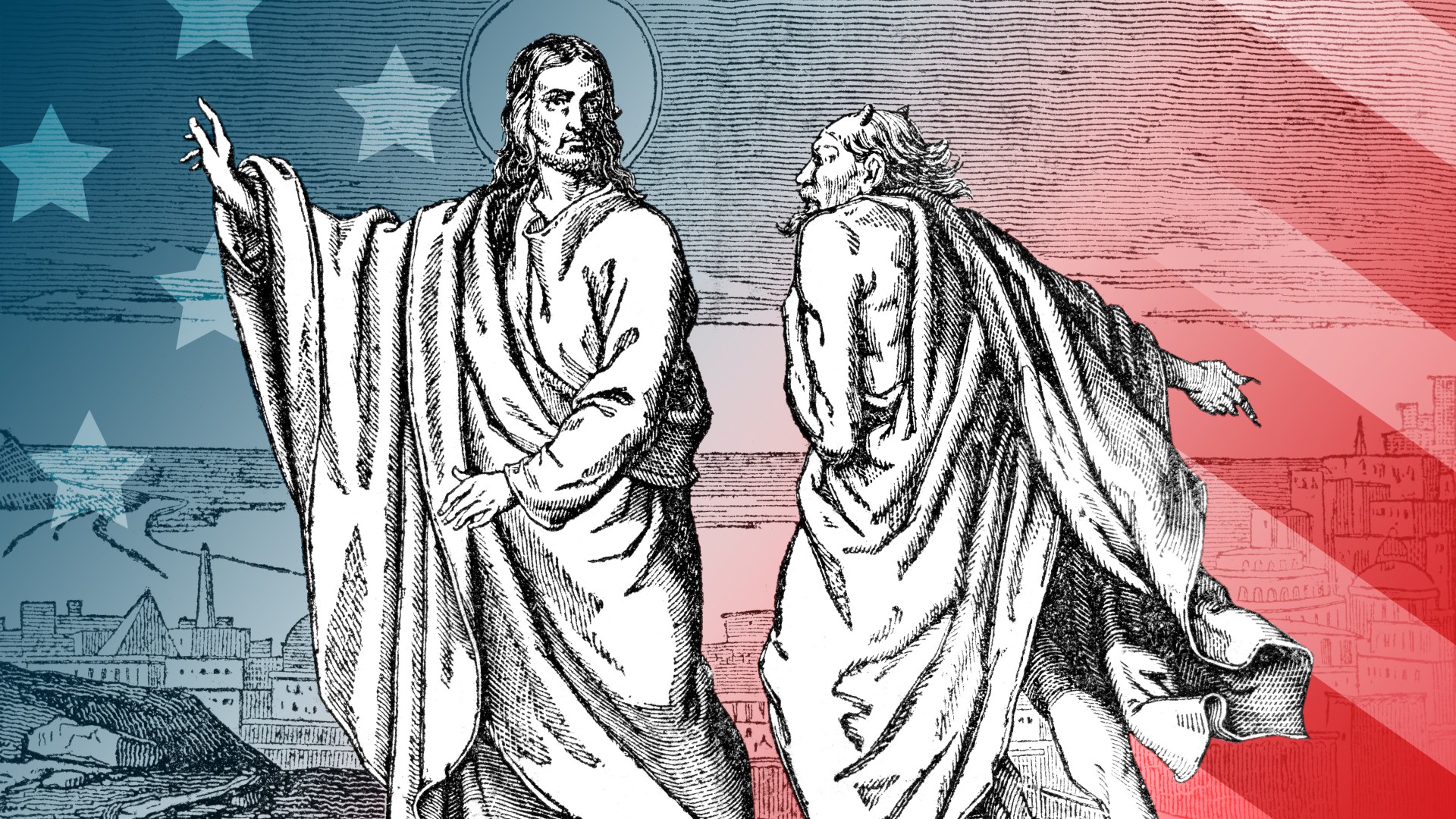

This call to humility, service, and even self-abnegation is integral to Jesus’ invitation to the upside-down kingdom of God, where the last are first and our weakness is occasion to display God’s strength—and it goes against our every fallen instinct. “All one’s ways may be pure in one’s own eyes,” as Proverbs 16:2 (NRSV) observes, allowing us to convince ourselves we only seek political power with the best of intentions and the purest of principles. But if good intentions and principles were a sure guard against idolatry, Satan couldn’t have tempted Jesus with “all the kingdoms of the world … their glory and all this authority” (Luke 4:5–6). It is the very potential to do good, in fact, that often makes the idolatry of politics and power so enticing. That is never truer than in times of intense political strife and opportunity, such as our present moment of pandemic, racial protest, and presidential campaign.

Burton’s Strange Rites trains its political coverage on three new movements, each born online but eager to reshape the offline world. First is the social justice movement—“social justice warriors” in the pejorative—critical equally of tradition and the rationalism and capitalism of the liberal order. Second is the “culture of Silicon Valley … [techno-utopians who] envision an equally radical account of human potential.” Third is what Burton dubs “new atavism,” a broad category encompassing everything from the “intellectual dark web” to the “black pill,” their commonality a vision of a hierarchical world where one makes meaning through sheer willpower—bootstrap existentialism, sometimes with a heavy dose of racism and misogyny.

Burton argues compellingly that these rising movements function as religions for their adherents, but I wondered if she was letting more traditional political alignments off too easily. Though certainly the content of a civil religion matters, the mere fact of it matters, too. When we so deeply invest ourselves in politics, particularly politics as acquisition of power, any political movement can provide us with the fixtures of faith: beliefs, rituals, saints, virtues, heresies—and an idolatrous claim of our allegiance.

Conventional political loyalties can be just as religious as the new trio Strange Rites examines, I suggested in a conversation over email. Burton agreed, pointing to the partisan fervency of many “white evangelicals, who overwhelmingly voted for [President Donald] Trump [and tend to] vote along GOP party lines.” Some “pockets of white evangelicalism” are particularly vulnerable to the “intuitionalism” and “best-self-ism” of remixed religiosity, she told me, especially those given to prosperity gospel teachings, interest in conspiracy theories, and instinctive distrust of established authorities. Mainstream Democrats have had difficulty “in recent years, around mobilizing behind a strong candidate the way, say, Trump voters have,” Burton noted, but a left-wing version of Trumpian civil religion is plausible: Oprah Winfrey once described then-candidate Barack Obama as a rare politician “who know[s] how to be the truth.”

The temptation of political power is sly. It confuses us about reality in a social climate Burton described to me as already ambiguous “about what is ‘real’ (physically, spiritually, socially, biologically).” Like the Devil in the desert, it lies about what we can have and what we should want, encouraging at once undue fixation on our present world—politics as a source of meaning, purpose, and community we ought to find in Christ—and too little true love for neighbor and enemy alike, especially those with politics unlike ours. “Our citizenship is in heaven,” we are too often inclined to forget, “and it is from there that we are expecting a Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ” (Phil. 3:20). That hope “is the same yesterday and today and forever” (Heb. 13:8), no matter what politics we face or what strange new rites arise around us.

Bonnie Kristian is a columnist at Christianity Today, a contributing editor at The Week, a fellow at Defense Priorities, and the author of A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (Hachette).