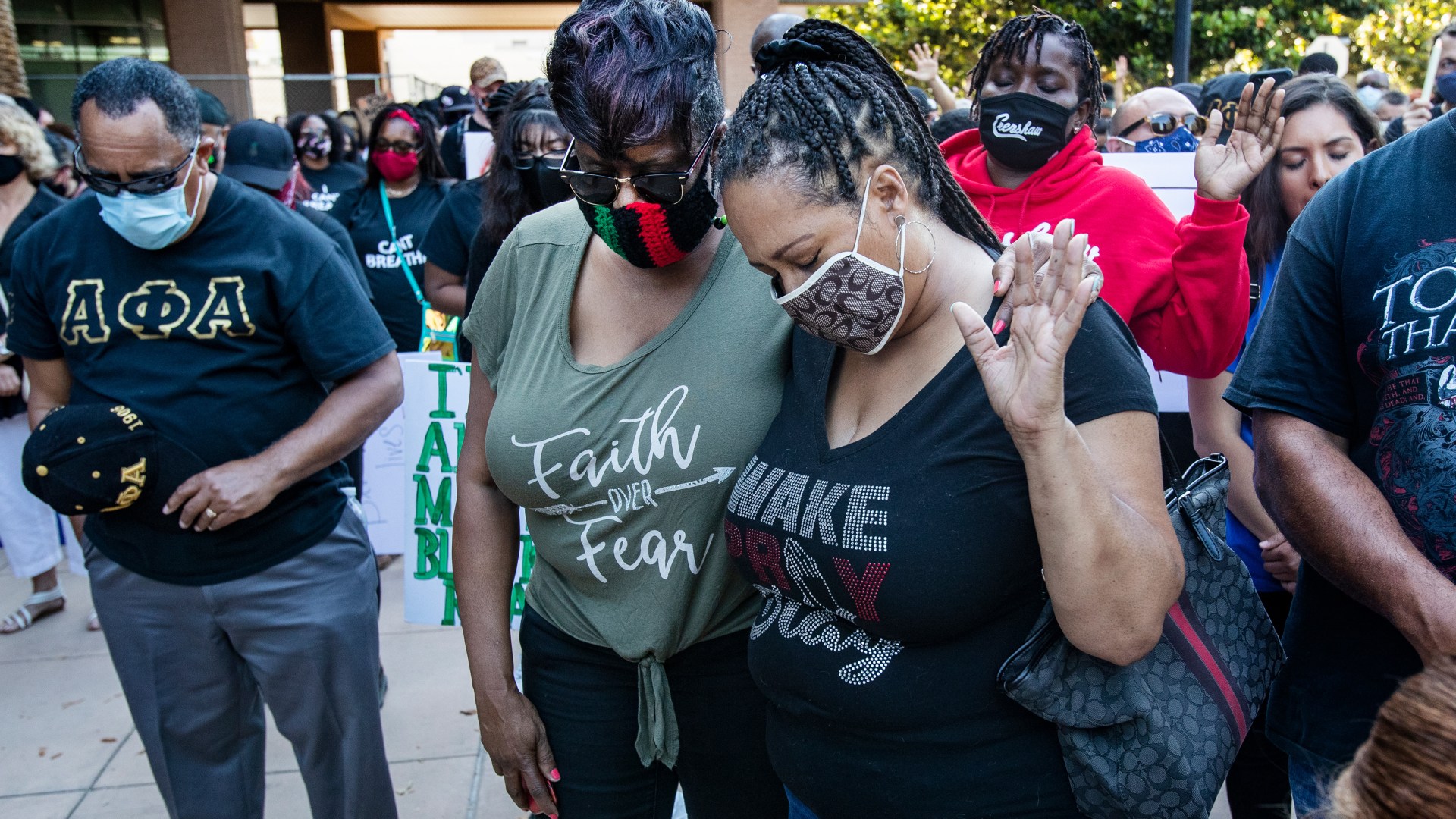

The entire globe is convulsing with social unrest and protests. Almost every day, I wake up to an endless stream of news that tempts me to despair. I look at the persistent racism and systemic oppression that mars our society, and I see no hope that things will change. I see political leaders failing to unify and not divide the country, and my trust in the system falters. I look at a church that so often views everything through the lens of a particular political party and not the gospel, and I feel downcast.

I take some small comfort in knowing that white Christians are stepping up to participate in public protests, analyze their organizations, and make room for change. But nonetheless, I’m still left with questions: Are black Christians seeing a momentary spike in sympathy, or is something deeper at work? Is a significant segment of the white evangelical church ready to join the fight for justice, or will the coming weeks and months see a return to the status quo? What will happen when there isn’t a steady stream of videos showcasing the undeniable face of black suffering?

There is an even more urgent question than whether white evangelicals participate in this movement. Our ultimate aim is not to secure allies; it is to secure freedom. With that in mind, can we really hope to slay or at least deeply wound the monster of racism that is so deeply imbedded in American culture?

In the context of this question, I sometimes go looking and praying for a sign. I need some signal that God has not abandoned us to human vice, that it is possible, in the words of Samwise Gamgee, for “everything sad … to come untrue.” I want to find room for hope when the reasons for it seem in short supply.

Where does my hope come from? Not from the usual places. Not from the fact that we’ve added more faces to our marches. My trust goes much deeper—to the Resurrection, and the way in which it reconfigures our spiritual imagination. God has a long history of giving his people a belief in the seemingly impossible.

Scripture reminds me of this story.

In the Gospels, the Pharisees ask Jesus for a sign that they might trust him. Instead of some trick or miracle that might comfort them in the moment, Jesus points toward something greater. He says to them, “For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of a huge fish, so the Son of Man will be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth” (Matt. 12:40).

When the disciples on the road to Emmaus say, “We had hoped that he was the one who was going to redeem Israel,” Jesus reminds them that it is necessary for the Messiah to “suffer these things and then enter his glory” (Luke 24:21, 26).

In both responses, Jesus points to the Resurrection. He knows that what his people need is not some small signal of God’s presence that can be dismissed as a coincidence. What we need is a sign of his victory. The feeding of the 5,000 or the walking on water is great, but if it can all be unraveled by death, then what is the point? If the Roman Empire has the ability to stop Jesus, then what is to keep the current empires from stopping us?

We need a hope big enough to overcome death itself. The Resurrection, then, is not a mere sign. It is a hermeneutical key that unlocks the mystery of God’s purposes. It is the power that overcomes principalities.

As I survey the history of race relations in America, I see this truth in play.

My ancestors knew that, in order to secure their freedom, slavery had to bend to the will of God and be destroyed. They knew that the Jim Crow era, despite its oppression, was not more comprehensive in its power than the Resurrection. We introduced Jim and Jane Crow to a Resurrection-empowered hope, and the civil rights movement was born. Similarly, what evidence do we have that today’s racial divisions can be defeated and that our societal sickness is not unto death? Our answer is the same: the empty tomb and the risen Christ.

Instead of looking for more signs, we need to be re-enchanted by the Resurrection. Instead of looking at the problems facing the church and the world through the lens of our Twitter feeds, we need to remember that Christ is risen and rules over all. His power applies to all of our enigmas. Racism and systemic oppression are not more difficult to overcome than death. And our hope for a transformed society comes directly from the risen Lord.

Let me be clear. This doesn’t mean that God is our genie and that we can rush into any arena assuming that he will rescue us from any folly or grant every request. It doesn’t mean that Christians can never feel discouragement. Here’s what it means: Our limited imaginations do not form the boundaries of what God can do. Humans have limited power; we can maim and kill or be killed. We can make promises of social unity that we often lack the power to actualize. But a God who has defeated death—and called to himself a people who understand the full scope of his victory—is unstoppable.

That belief in an unstoppable God is precisely what made the early church so difficult to control. It made them dangerous.

After the birth of the church, “Christians became a nation within a nation, a new oikoumene or universal commonwealth that spanned the known world, crossing traditional cultural barriers,” writes Gerald L. Sittser, author of Resilient Faith: How the Early Christian “Third Way” Changed the World. “Their primary loyalty was to fellow believers, not nation or race or tribe or party or class.”

How do we regain that vision today? How do we claim a resurrected Christ as our reason for hope?

I must confess that much of my life has been spent doubting the Resurrection. I don’t question whether it occurred—I am convinced that the tomb remains empty. But I do often wonder whether the world is truly a different place. Things seems to go on as they always have: The rich exploit the poor. Evil triumphs over good. Going low appears to be much more profitable than going high. Racism sweeps our land, and the weakest among us suffer the most.

As I watch the news these days, I see genuine expressions of sympathy for the black situation in America. But I don’t simply want people to feel sorry for us. I want freedom. And in my best moments, I remember where that hope for freedom resides. It resides in the God who conquered death. Although the full fruition of that freedom will not come on this side of heaven, nonetheless, I am not forbidden the beginnings of it here and now. By desiring freedom now, I am not turning America into the kingdom. I am demanding the right to live and love and work as a free black child of God.

The defeat of death is God’s great triumph. It reshapes the Christian imagination, forever obliterating the limits we place upon our Creator. As the protests press on, then, I pray today and every day that we remember the Resurrection, when the entire cosmos became something different. We have yet to realize the full scope of that change.

Esau McCaulley is a priest in the Anglican Church in North America, an assistant professor of New Testament at Wheaton College, and the author of the forthcoming book Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope (IVP Academic). Speaking Out is Christianity Today’s guest opinion column and (unlike an editorial) does not necessarily represent the opinion of the publication.