Marriage is hard. Plenty of institutions attest to that: couples therapy, couples retreats, and, of course, divorce. But a good marriage isn’t just difficult to sustain; it can be difficult to get off the ground. For many who want to tie the knot, finding a mate is the least of problems amid more daunting financial or cultural headwinds.

Societies have tried to jump-start marriages over the centuries with the vehicle of the mass wedding. Collective wedding ceremonies date back at least to the fourth century B.C., when Alexander the Great and roughly 80 of his officers married Persian women to cement their rule over the region. But the practice really took off in the later 20th century. Sensational instances like Moonie marriages and city hall LGBT ceremonies have tended to grab headlines. Far more common, however, are mass weddings put on by churches, mission groups, nonprofits, and even national governments such as those of India and Syria. These rites are meant to nudge couples past cold feet and sticker shock and toward the benefits that come with mutual commitment and legal recognition of a marriage union.

One of CT’s most popular articles online last year was an interview with Dallas pastor Bryan Carter about his church’s tradition of the “Grand Wedding.” More than 80 couples have been married so far in collective ceremonies at Concord Church, part of a program to get lovers to stop living together and make some real vows. The church seeks to remove as many excuses for non-commitment as possible. It covers all wedding costs, provides more than a year of marriage counseling and mentorship, and even pays a month of rent for cohabitating couples who choose to live apart instead.

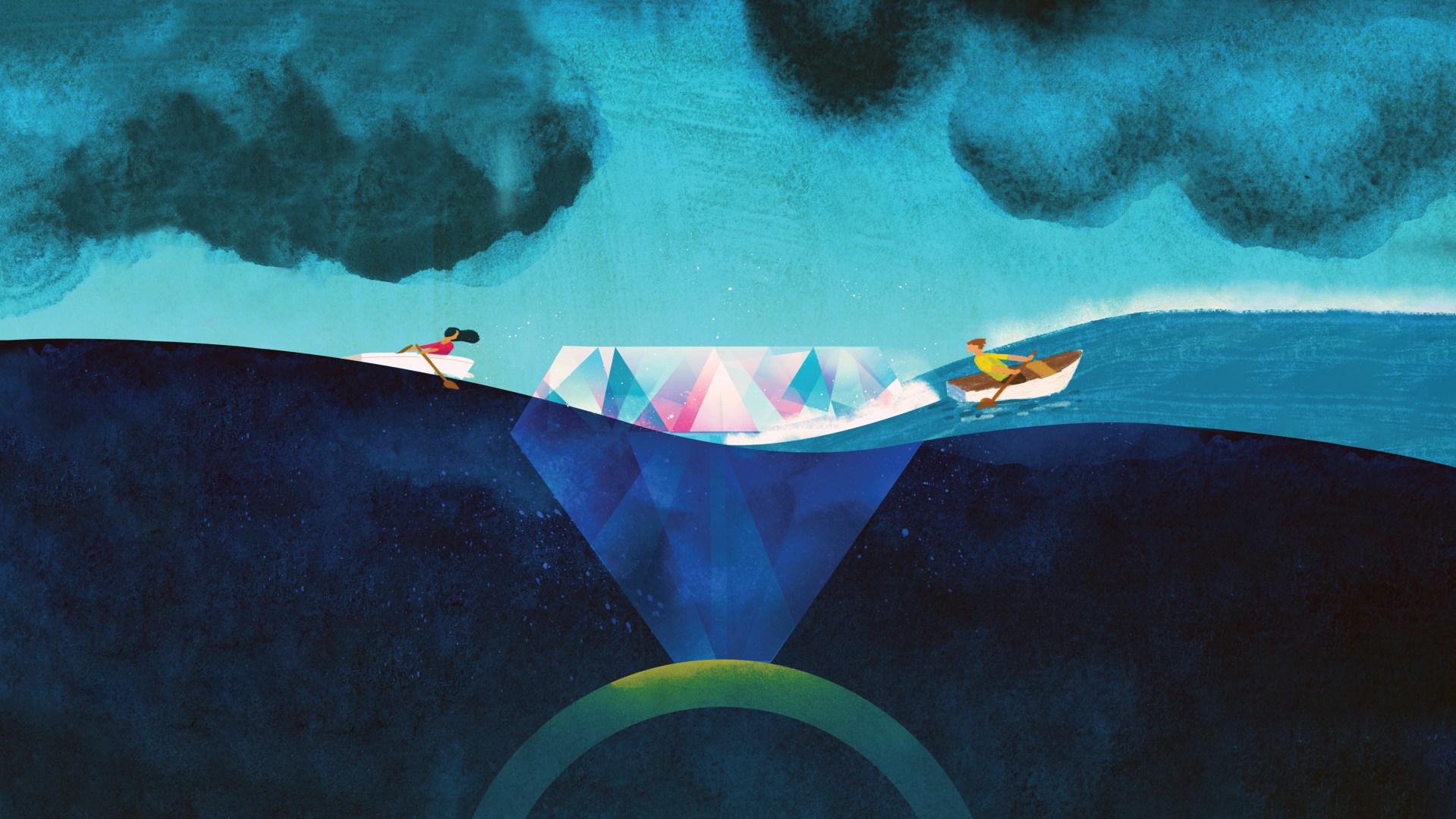

For the most part, initiatives like Concord Church’s offer couples a bridge over relatively surmountable obstacles, getting them to a destination they would genuinely like to reach. The alarming reality outlined in our cover story by sociologist Mark Regnerus, however, is that most couples no longer see anything worthwhile across that bridge. The rapid loss of interest in matrimony is not due to its prohibitive cost but rather to its lack of perceived benefits. This comes even as, ironically, those who have already crossed the bridge are finding that marriage offers unparalleled shelter in stormy times, including global pandemics.

This shifting landscape poses massive challenges for those who champion the value of marriage. Can matrimony be saved? The answer probably will not depend on legislation or messaging. More likely, salvation will hinge on how well communities—particularly church communities—model marriages that provoke people to say, as Carter told CT: “That’s what I need. Help me to get there!”

Andy Olsen is managing editor of Christianity Today. Follow him on Twitter @AndyROlsen.