The coronavirus pandemic and its economic fallout are exacting a devastating toll on American families. Millions of parents have lost their jobs; tens of thousands of people are dying, including many grandparents; and mothers and fathers all over the country are contending with a volatile, uncertain future that will shape their lives and their children’s lives for years to come.

What does all this mean for marriage?

Some American couples hit directly by unemployment are more likely to divorce—at least if the husband is the one losing his job. We know, for example, that men without full-time jobs are about 33 percent more likely to get divorced, whereas women’s unemployment doesn’t boost the risk of splitting. Conflict and violence at home may also increase due to economic uncertainty and the stress of the lockdown. A recent analysis by The Economist of data from five big cities indicates that while most types of crime have declined, reports of domestic violence have gone up.

As sociologist Mark Regnerus notes, the marriage rate was already dropping prior to COVID-19, hitting a record low in 2018. The current recession will drive the marriage rate down even further because couples are reluctant to tie the knot when their economic prospects are uncertain. The people hit hardest by this marital decline will be those with the most precarious economic fortunes—the less educated and the working class. And in the end, a staggering share of today’s young adults—at least one-third by one estimate—will never marry.

The ongoing retreat from marriage, coupled with economic strain and falling fertility, means that by the mid-21st century, millions of Americans will be what the Chinese call “bare branches”—that is, men and women without kin. Many of these bare branches will not be prepared for the storms brewing on the horizon, be they recurring pandemics, social unrest, a sovereign debt reckoning, or additional economic crises. As they face the baleful winds of change, these men and women will not have the economic, social, or emotional support that they need in midlife and especially late life. And many of these men and women will lack the meaning, direction, and happiness afforded by marriage and family life. All this will be especially true for kinless Americans with no religious home.

That’s the bad news for the American family.

However, in the midst of all this tumult, there just might be a silver lining: The “soulmate” model of marriage will most likely fade and a “family-first” model of marriage will emerge. This family-first marital environment will be stronger, more stable, and more likely to offer a secure harbor for children.

The soulmate model of marriage, which took root in the 1970s, rests on the idea that wedlock is primarily about an intense emotional or romantic connection between two people that should last only as long as that connection remains happy, fulfilling, and life-giving to the self. We see the soulmate story in thousands of songs, hundreds of Hollywood movies, and just as many self-help books. Think Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love or the song “10,000 Hours” by Dan + Shay and Justin Bieber. This popular myth is part of why men and women go into marriage with extremely unrealistic expectations, and these expectations then set them up for devastating disappointment and often divorce.

The soulmate model was also predicated on particular economic and political conditions. Psychologist Eli Finkel has argued that, starting five decades ago, husbands and wives felt free to climb what he calls “Mount Maslow,” referring to the hierarchy of needs defined by psychologist Abraham Maslow. The idea here is that as the market and the state took care of more and more basic needs like food and shelter, and as Americans depended less on their families to meet those needs, married couples felt free to focus on seemingly more exalted “self-actualization” needs, like emotional connection, personal fulfillment, and marital happiness.

However, in the darker and more difficult world that we now face—one marked by economic insecurity, ongoing disease, and governmental impotence—this soulmate myth will become less realistic and less appealing for most men and women. Husbands and wives will come to see how little they can depend upon the government and the market and how much they have to lean on one another—to nurture (and school) their children, tend their garden or home, launch a home business, or help care for an older parent. They will rediscover matrimony as a space primarily dedicated to raising children, where lifelong commitment and community support—including that of a local church—are essential. In other words, they will re-learn all the ways that marriage is about much more than the fluctuating feelings between two people.

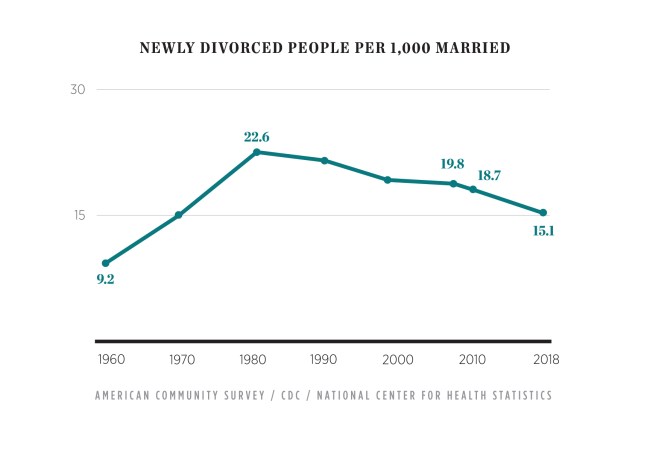

After COVID-19, most marriages will not collapse but instead grow stronger. Recent history gives us a reference point. According to my research, hardships during the Great Recession led many Americans to deepen their marital commitments and, in many cases, cancel their plans to divorce or separate. In fact, the divorce rate has fallen by more than 20 percent since the last recession, as Americans became more committed to and cautious about married life.

The family-first model depends on a “till death do us part” ethic. An Institute for Family Studies survey conducted recently in California shows that couples who embrace this ethic are less likely to worry about divorce than those who believe that separating is a viable option. These committed couples are also more likely to be happily married. Among Californian husbands and wives, 77 percent of those who took a more contingent approach to commitment—“I’m in this marriage so long as our love lasts”—were satisfied in their marriage. But 82 percent of those who reported that “divorce is not an option” said they were satisfied. Undoubtedly, taking a more committed approach to marriage gives couples a greater sense of trust, emotional security, and confidence for the future—all of which boost their odds of being happily married.

As marriages become stronger and childbearing becomes more selective, the share of kids being raised in intact families will go up, increasing the family stability advantage for many American children. We’ve already seen this happen in the wake of the Great Recession. Declines in divorce and declines in the share of babies born outside of wedlock have led to an uptick in the share of children being raised by their own married parents. During and after the pandemic, family-first marriages will accelerate this trend.

Moreover, we’ll see that Americans who stay married will emerge from this pandemic in better emotional and financial shape than single Americans or those who divorce. In general, research shows that married adults tend to be significantly happier than single adults. And a recent study that I conducted with Peyton Roth of the American Enterprise Institute shows that married Americans are about 30 percent less likely than single Americans to report being lonely. Wedlocked couples will also enjoy better economic security, earning more income than their single counterparts, saving more than unmarried Americans, and turning more easily to kin for financial support.

In a family-first marriage, the emotional communion between husband and wife motivates their matrimony, but so too does a concern for giving their children a stable home, keeping their heads above water financially, helping other family members, and honoring their vows to remain together. The church is especially well-positioned to play a supportive role in this “till death” model of marriage, both within the pews and in the broader community. Research from the Institute for Family Studies (where I’m a fellow) finds that couples who stay actively involved in their religious communities and pray together regularly are much more likely to enjoy vibrant marriages. As Regnerus notes, churchgoing Christians are also much more likely than other Americans to get married in the first place.

Although much about our world is bleak and will be for some time, the post-pandemic future for married families looks bright, with wedlock emerging stronger, more stable, and better positioned to provide the secure foundation that children need to thrive. All of this will be especially true for the faithful.

W. Bradford Wilcox is the director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia and a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies. Alysse ElHage is the editor of the Institute for Family Studies blog.