I’m a woman trapped in a man’s body.” Only a generation ago, few Americans would have regarded this statement as coherent and believable. Yet today, someone who comes out as transgender can earn cultural cachet, while those who question the new orthodoxy are increasingly branded as bigots or worse. This shift in cultural attitudes is only the latest triumph of the sexual revolution that has radically reshaped sexual categories and behaviors over the past several decades in America. Yet the roots of this revolution go back much further.

When determining why revolutions happen, social scientists often distinguish between three types of causes: preconditions, precipitants, and triggers. Preconditions are the long-term structural factors that make revolution possible. Precipitants are the short-term events that combine with these structures to make revolution plausible. Finally, triggers are the immediate catalysts—the sparks that ignite and make revolution actual.

The sexual revolution and its triumphs result from a similar mix of immediate, short-term, and long-term causes. Yet cultural commentators tend to focus only on triggers, acting like police officers or insurance adjusters who arrive at the scene of an accident to determine the extent of the damage or who’s at fault. These roles are important, but they only scratch the surface of how the church should respond to the sexual revolution.

A more holistic response requires a more holistic understanding that can only be achieved by sorting out the long-term structural causes of the revolution from its short-term and immediate causes. This sorting is precisely what theologian and historian Carl Trueman aims to do in his latest book, The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism, and the Road to Sexual Revolution.

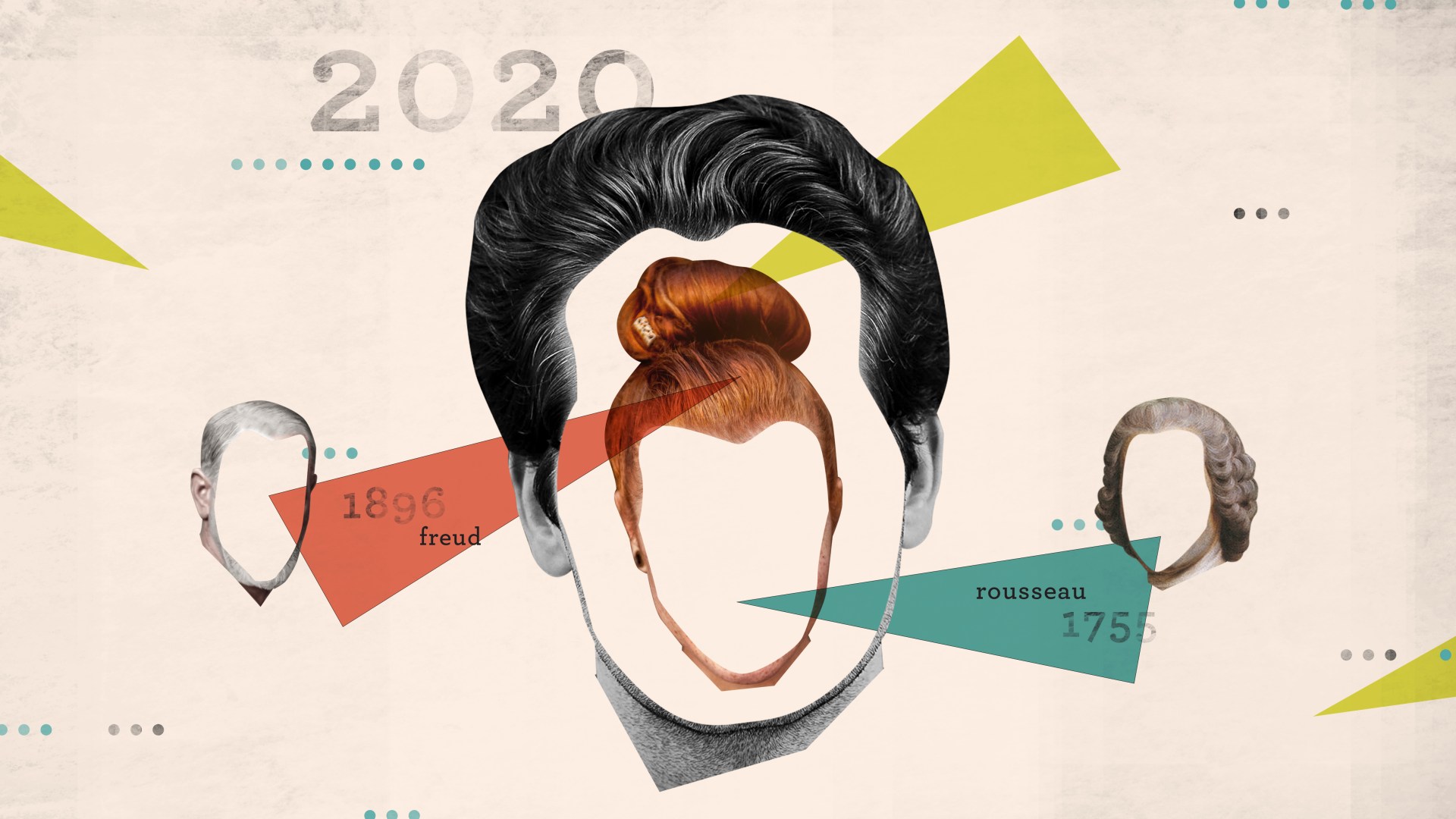

Trueman’s basic contention is this: The sexual revolution is a symptom rather than the cause of efforts to redefine human identity. Centuries before the nation swooned when Bruce Jenner debuted as Caitlyn, for example, intellectual shifts were taking place that would make a cultural event like this possible. What Trueman offers is the story of those shifts.

Reimagined Selves

Trueman begins by diagnosing the state of modern Western culture so that, throughout the rest of the book, he can trace some of its intellectual preconditions. Here, he relies heavily on the work of three key thinkers: philosopher Charles Taylor, psychologist Philip Rieff, and ethicist Alasdair MacIntyre.

Of particular importance to Trueman’s narrative is the idea of the “social imaginary,” the term that Taylor uses to describe a society’s basic intuitions about the world and the place of human beings within it. As each of us goes through life, we tend not to operate on the basis of a self-conscious commitment to a particular set of ideas. Instead, the process is much more intuitive. For example, only a generation ago, the claim “I’m a woman trapped in a man’s body” was widely understood to be nonsensical. This understanding owed less to a deep theoretical knowledge of gender and sex than it did to the widespread intuition that the world has an established order and meaning to which we must conform.

Today, the social imaginary has been radically reimagined. People tend to see the world and themselves more as raw material that they can bend and shape to suit their own purposes. This reimagining wasn’t the result of learning new truths about the physical world but of subjugating the physical to the psychological. The modern idea of self has become thoroughly psychologized: One’s identity is defined not by a relationship with the external world but by an individual, internal sense of happiness. On this basis, the modern person operates according to what Taylor calls “expressive individualism,” desiring both to express an internal sense of self and to have that sense of self recognized and accepted by the external world.

Drawing from MacIntyre’s work, Trueman explains that expressive individualism has become the default mode of modern society. Because we lack a common framework for understanding who we are and why we exist, our moral discourse has degenerated into expressions of personal feelings and tastes. In order to satisfy our moral preferences, we feel we must be liberated from the repressive constraints of objective moral claims. Such liberation requires a full-scale campaign of cultural iconoclasm, of dismantling and disavowing the ideas and artifacts of the past so that we might pursue happiness on our own—thoroughly psychological and distinctly sexual—terms.

Revolutionary Shifts

After diagnosing the state of modern Western culture, Trueman spends the bulk of the book showing that our reimagined sense of self is rooted in intellectual shifts that had been taking place for several centuries.

The first shift was the psychologizing of the self—in other words, making one’s feelings and desires foundational to one’s identity. Trueman highlights the work of the 18th-century Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who laid the groundwork for this shift by arguing that we can only live authentically when our outward behavior can match our inner psychology. In a revolutionary step, Rousseau gives ethical priority to one’s psychology, claiming that society is the enemy of the authentic self because it forces people to suppress their desires and conform to conventional morality.

At the turn of the 19th century, Rousseau’s heirs within the Romantic movement—particularly the poets William Wordsworth, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and William Blake—were instrumental in popularizing this psychological view of the self. Yet for all their calls to cast off the repressive influences of civilized society, these Romantics—like Rousseau—were confident that nature possessed a purposeful order upon which humans could build their lives. By the end of the 19th century, such confidence was greatly undermined by the work of Friedrich Nietzsche, Karl Marx, and Charles Darwin. To Nietzsche and Marx, belief in transcendent reality and purposeful order are symptoms of psychological weakness and social sickness. Then, Darwin’s writings on evolution dealt the death blow by providing a new story of humankind that reduces human nature to something fluid and directionless.

With the belief that personal identity is psychological and self-determined, the stage was set for a second intellectual shift: the sexualizing of psychology. It was Sigmund Freud, the father of modern psychology, who in the early 20th century championed the insidious idea that’s intoxicated modern society: Self-identity is grounded in sexual desire. We’re essentially psychological, says Rousseau. Yet our psychology is essentially sexual, says Freud. Therefore, we’re essentially sexual. With Freud, sex is transformed from something we do into who we are.

After this transformation, it was only a matter of time before a third intellectual shift occurred: the politicizing of sex. Two Freudian acolytes, psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich and philosopher Herbert Marcuse, drove this shift by merging Marxist ideas of political oppression with the Freudian notion of sexual repression. They argued that, because humans are essentially sexual, there can be no political liberation without sexual liberation.

In response, from the mid-20th century to the present day, a bevy of writers and activists from the New Left have aimed for sexual liberation by attacking the most problematic of all bourgeois institutions: the nuclear family. As long as the nuclear family is considered good and necessary to the right ordering of society, allegedly repressive norms such as heterosexuality and monogamy will perpetuate an oppressive social hierarchy that rewards sexual conformity and punishes those who wish to follow their own sexual codes. On this understanding, political liberation depends on sexual liberation—which depends on the dismantling of the nuclear family.

Though not everyone reaches the same conclusions, the underlying association of political liberation with sexual liberation is widely assumed today. Even if they’ve never read the writings of Freud, Reich, Marcuse, and the New Left, many people intuitively believe that open and unqualified expression of sexual desire is essential to human identity and dignity.

It’s this revolutionary belief that has transformed our “social imaginary” and led to a swift and stunning series of triumphs for the sexual revolution. Trueman devotes several chapters to detailing three triumphs in particular: the pervasiveness of eroticism in art and pop culture, the prioritization of psychological well-being in academic settings and legal or ethical arguments, and the widespread embrace of transgender identity.

Yet, as Trueman reiterates throughout his book, the triumphs of the sexual revolution are not as swift and stunning as they appear. Instead, they’re the latest logical outcomes of a society that has accepted expressive individualism as its basic premise. The road to sexual revolution was long and marked by a series of intellectual turns that were hardly inevitable. But once chosen, they led Western culture to where it is today.

Road to Renewal

As a preeminent church historian, Trueman is well-versed at telling the stories of intellectual turns and tracing their cultural consequences. Yet here Trueman’s aim is more modest: Rather than showing precisely how the ideas that undergird the sexual revolution have come to permeate our culture (for this would take many volumes), he intends only to show that these ideas aren’t new but have been preconditioned by several centuries of intellectual shifts. In this aim, he succeeds marvelously.

Yet certain segments of the book would have benefitted from some attention to causation. I’ll give just one example: By moving from Rousseau (chapter 3) to Wordsworth (chapter 4) in his narrative, Trueman implies a causal relationship that’s hardly clear. Though Wordsworth emphasizes the internal life of the poet, in his preface to the Lyrical Ballads he reins in any excess expressivism by describing the true poet as one “who being possessed of more than usual organic sensibility, had also thought long and deeply.” Also, Wordsworth’s reasons for using everyday language echo the literary choices of earlier poets like Dante, who in De Vulgari Eloquentia insists that vernacular is “natural” and “more noble” than the “artificial” language of educated elites. Further, Wordsworth's distinction between poetry and history stands in the tradition of Aristotle and the poet Sir Philip Sidney.

So, it could be that Wordsworth owes more to Rousseau than to these earlier poets, but the lack of a clear causal connection blunts Trueman’s dramatic claim that “Wordsworth stands near the head of a path that leads to Hugh Hefner and Kim Kardashian.” A similar lack of causal explanation blunts the force of other conclusions that Trueman makes throughout the book.

Yet this critique should take nothing away from the fact that The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self is a signal achievement of cultural analysis. Readers wishing to understand the cultural convulsions and social upheavals taking place in the West will find this an indispensable book. It’s a masterclass on the fact that, while all ideas have consequences, some ideas are more consequential than others. Trueman shows that the consequences arising from ideas about human nature and identity can be especially revolutionary.

This fact should help guide the church’s response to the sexual revolution. Just as the revolution was made possible by certain preconditioned ideas about human nature and identity, any successful counter-revolution must arise from preconditions of its own. The church must lead the way by articulating and modeling a vision of true human identity and community. And we must do this with the knowledge that we’re unlikely to see any significant change in our own day. The road to sexual revolution was long, and so too will be the road to renewal. But it’s the only faithful road, and so it’s the one we must take.

Timothy Kleiser is a teacher and writer from Louisville, Kentucky. His writing has appeared in National Review, The American Conservative, Modern Age, The Boston Globe, Front Porch Republic, and elsewhere.