The cashier at Trader Joe’s couldn’t get over how many fresh flowers customers have been purchasing during the pandemic. “People load up their carts with pasta and frozen foods and then they buy at least two bouquets of flowers,” she told me. “It doesn’t really make sense.”

Beauty persists, especially in times of uncertainty or hardship. Holocaust survivor and concert pianist Alice Herz-Sommer performed at more than 150 concerts during the two years she spent at Theresienstadt concentration camp. She later told a reporter, “People ask, ‘How could you make music?’ We were so weak. But music was special, like a spell … the world is wonderful. It is full of beauty.”

While some of us are first responders or have lost a loved one to COVID-19, most of us are contending with circumstances far less devastating than Herz-Sommer’s. Still, death stares at us hourly through the garish news graphics tracking the many lost to the virus.

“Living each day under the stress of the pandemic, our need for beauty is on the surface—we are feeling it, even if we can’t fully articulate it,” said Charlie Peacock. The four-time Grammy-winning composer, producer, and recording artist has worked with everyone from Switchfoot to The Civil Wars. “Gratefully, the vocational beauty makers are working overtime to fulfill this need. When has there ever been a time when so many artists of every kind are sharing beauty with the world—for free?”

He is creating new music and paintings daily while self-quarantining in Nashville, including a song with friend Sarah Masen Dark. “It did not start out to be any commentary on our new world, but in gradually learning what my own work was making me think and feel, I do believe it is linked.”

Peacock is not alone. Poets, painters, philosophers, and theologians have historically championed the conviction that beauty is even more essential during our darkest periods.

Pope John Paul II affirmed in his 1999 “Letter to Artists,” that “society needs artists, just as it needs scientists, technicians, workers, professional people, witnesses of the faith, teachers, fathers and mothers.” This pandemic requires first responders, scientists, grocery store clerks, delivery people, and, yes, artists who recognize their responsibility, as Pope Francis put it, to be “custodians of beauty, heralds and witnesses of hope for humanity.”

Scientists may try, but beauty can’t be measured by the same data that defines our disposition right now.

“It is not something we can possess. Beauty is the outcome of truthfulness, mastery and goodness working together,” encaustic painter Marissa Voytenko told me. She uses the ancient technique involving hot wax to create abstract works that have been exhibited across the US and the Ukraine. “When life becomes too heavy to bear and circumstances too dark to see a way forward, beauty has the ability to alleviate fear and offer hope.”

Mary Amendolia Gardner, a priest and spiritual director in Northern Virginia, leads seekers and believers in visio divina, or holy seeing, a spiritual practice to help focus distracted minds. She asks participants to sit in front of a work of art for five to ten minutes to become more aware of God’s care and attention in their lives.

“In times of uncertainty, sickness, despair, and death, beauty is more than a mere distraction,” she said. “Beauty is a human connection point which becomes a catalyst of connection to the transcendent.”

Many of the world’s finest museums are offering free virtual tours to provide encounters with extraordinary works of art. Many larger-scale masterpieces in these galleries exquisitely evoke human suffering through the ages and press us to contemplate our own mortality. There’s value in being reminded of this by studying a painting instead of another news story or graphic.

In her book On Beauty and Being Just, Yale philosopher Elaine Scarry observes that beauty has the effect of “radically decentering” us. Others have argued that reflecting on works of beauty in times of pain and affliction is misguided. German émigré philosopher Theodor Adorno famously declared that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” But Scarry suggests the opposite, that beauty actually opens us up to the inequities and injustices of human life.

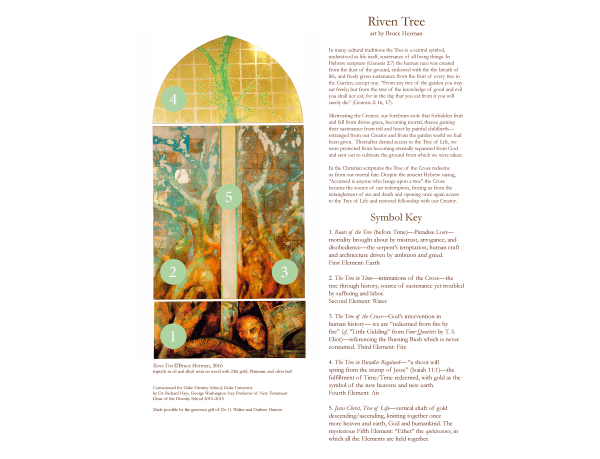

Bruce Herman has been reflecting on T. S. Eliot’s Notes Towards the Definition of Culture while currently sheltering at home. In his post-war essays, Eliot considers how artists, authors, philosophers, and theologians can continue to “meaning-make” in the face of futility and loss. Herman insists it is imperative to make music, art, and poetry when the world we know has been shattered.

Herman is a professor at Gordon College and a painter whose works are in the permanent collections at the Vatican Museum of Modern Religious Art and the Hammer Museum, among others. He has lost three brothers, both parents, his grandparents, and other family members to suicide, cancer, and other maladies.

“I am no stranger to grief and death and suffering,” he said.

Yet I continue to believe that beauty not only can be pursued in such a time as ours, but it must be pursued. … Beauty is not pasted over suffering but grows out of it—like the proverbial shoot from parched ground—breaking the hardness of concrete or asphalt with green growth and hope.

Is the longing for beauty something only healthy, well fed and sheltered people have? The proof against this is everywhere from the caves of Lascaux to the Sistine ceiling; from Shakespeare to the hymns written in time or war and loss.

In his essay Beauty in the Light of the Redemption, Dietrich von Hildebrand defends beauty against arguments that it serves no practical purpose: “The function of the senses and of the visible and audible contents in this experience is of a modest, humble kind: they are a pedestal, a mirror for something much higher.”

We typically dash through the world, barely noticing our surroundings or staring at our phones as one image quickly replaces the previous one. Now, as we settle into six weeks of self-quarantine, we have an opportunity to practice a new discipline—to actively notice the beauty on offer all around us, to go back and look or listen again. Far from distracting us from what is essential, beauty can draw us closer to all that is good and holy and healing.

Jody Hassett Sanchez is a journalist and documentary filmmaker. Her film More Art Upstairs, which explores questions about art and beauty, is available on iTunes and Amazon Prime.