Eight years ago, my intestines stopped working. They’d been grumbling for years, but who really expects their body to go on strike. It was painful and, occasionally, messy. My body ached and my life contracted. Doctors told me it was stress, or the flu, or food poisoning, but the pain grew worse and I started missing work. My personality changed.

After three years, I got a diagnosis: Crohn’s disease. Communication can break down between the immune system and bacteria living in the gut. We usually get along with these “symbiotes,” these creatures living with us and within us. Even the famous E. coli usually lives in harmony with human hosts, part of a vast digestive ecosystem. Countless tiny organisms—bacteria, archaea, and protists—help us tackle our food. Except, sometimes they don’t.

In Crohn’s disease, something disrupts the delicate balance, causing inflammation and allowing bacteria to grow out of control. In severe cases, they eat their way out of the intestines, cutting holes that doctors have to stitch together. More often, drugs can keep them contained, though no one knows exactly how. Much of biology, even human biology, remains a mystery. Five years experimenting with medicine and diet restored some normalcy, but I have become more mindful of “my” body and my relation to it.

Body and Soul

At first, the Christian view seemed simple. My earthly body is a temporary home for my eternal soul. When everything worked, I viewed my soul as a mind, driving a body. Like my car, my body might be unresponsive, but I always knew the difference between me and it. Didn’t Jesus say that the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak (Matt. 26:41)?

But with Crohn’s, I wasn’t steering. Nor was my car. It was the passengers, the bacteria. By changing my body, they changed my mind. Pain ruined my mood and colored my choices. I became less patient, less kind; I was irritable and resentful. Strangely, my will became a matter of consensus.

Before getting sick, I thought my will was the most important part of my self. Even when it failed to rule my flesh, it was still free to seek the good. But what if my will was not free? What if it was bound to my body and my bacteria? What if my decisions were always communal?

Worse yet, if I was not distinct from my body, how could I understand suffering? I was no longer distinct from the world; I was part of it all. To be a body is to be limited, bound to suffering and death. If my will was so linked to the bacteria, was the very core of me also bound? What then became of eternal life? I gained a visceral appreciation for my limits, for pain and suffering and insufficiency. I found it hard to forgive God this indignity, this loss of self.

Body and Biology

I needed a new story, a new way to speak of body and soul. I have a doctorate in biology from Harvard and spent many years working with NASA on the search for life in space. Surely this could help me understand life and self. What story could I tell as a scientist?

I began looking into organisms and individuality in science. Life appears intimately tied to metabolism—the chemistry of nutrition and growth—and to reproduction. In both, organisms are surprisingly interdependent. Biologists can speak confidently about the processes, but not as much about the boundaries of life.

Over the long-term, the biological story seems to be ruled by entropy and symbiosis. Entropy is a fancy word for disorder, formally the energy in a system unavailable for work. “Entropy” may also be shorthand for the long-term increase in disorder within a system (Newton’s second law of thermodynamics). Disorder increases unless you add work. Think of your home. You put food in the kitchen and clothes in the closet so that you can eat and dress when you want to. You stock up on order, use it all up, and then stock up again. Life does this in the universe. The physicist Erwin Schrodinger called life negentropy, local stockpiling of order and energy in organized systems, “organisms.”

Physicists think that the universe as a whole is slowly running out of order. In the beginning matter and energy were neatly packed into a single point. At the end, all of it will be spread about. Organisms tidy up locally, but are still part of the overall trend. They forage broadly, to stock up at home.

The story of entropy is a tragedy. Throughout our lives, we consume more than we produce. We eat animals, who get their energy from plants, who get their energy from the sun. Eventually—billions of years from now—the sun will run out of energy and Earth will no longer be habitable. We will survive until the cosmic larder is empty.

Other organisms can help us use energy more efficiently. Thus, entropy explains symbiosis. When we farm, we use plants and animals to store up energy for us. We enlist them in our quest for order. We also use bacteria, giving them a home in our guts so they can digest food and pass the nutrients on to us. Life’s challenges require symbiosis.

For humans, the challenge is greater. Our ability to think, feel and choose lets us order the world extremely well, but it takes tremendous energy. We cooperate with myriad organisms, from corn and cattle to gut bacteria to the yeast in bread and wine. Biologists may one day explain consciousness and reason (or they may not). If they do, I suspect they will find that minds require complex symbioses—countless species working together to fight entropy.

Communal embodiment is not only real, but necessary. The locus of self and will for a biologist must be an interdependent community. In everything I do, “I” am both Homo sapiens and E. coli and other species collaborating in a single consciousness. I am legion.

Soul and Scripture

Crohn’s made me take Ecclesiastes 1 and Romans 8 more seriously. All is vanity. Physics and biology can’t provide identity, freedom or salvation. Nor can I blame them for limitation and suffering. It was God who subjected creation to futility. My mind was no freer than my body, at least in the ways I wanted it to be.

At the time, I was preparing a book on how we have defined life historically, from the chemical life of bacteria and plants, to the interactive life of animals, and the particular life of humans. Early theologians helped me think through life and death in a new way, to think about what it means to die to self. My body, my mind, even my soul (were it mine alone) can never escape vanity and futility. True life is divine life—the very breath of God. God’s spirit is willing; my flesh is weak. True autonomy and independence cannot be found in the physical world.

Perhaps God, creating us for community, revealed something in this. “It is not good that the man should be alone.” (Gen. 2:18) Perhaps entropy and symbiosis show us that true life is always bound to, and bounded by, the life of others. “Indeed, we felt that we had received the sentence of death so that we would rely not on ourselves but on God who raises the dead.” (2 Cor. 1:9)

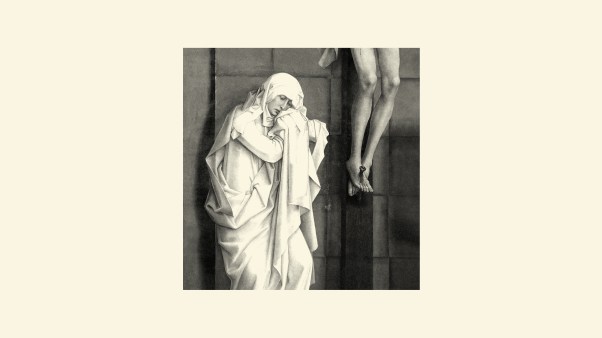

It sounds odd to include bacteria in the body of Christ but, if God intends to reconcile the whole world, we should consider it. God dwelt, in fullness, within the messy, intertwined, and dependent body of Jesus. He made grace visceral, from Mary’s pregnancy to Jesus’ last breath to his first bite of fish in the resurrection.

My Life and the Life of the World

I tell many stories in my life. My own story (were it mine alone) can only be a tragedy, a frail body and a compromised mind. The biological story, life on Earth, is also a tragedy of suffering and death, though it has a certain grandeur as it flowers and fades. The Christian story is something different. It passes through death into life and, I begin to believe, God set it up that way.

We fell away from grace, both spiritual and visceral. We lost our place. But God is constantly reconciling us, to God and to one another. My separateness is not the miracle, but the mistake. God calls me back into the body of Christ. That is a story worth telling.

I take my Crohn’s as a reminder to love God and to love my neighbor—as alien and frustrating as my neighbor might be. For neither death, nor life, nor entropy, nor symbiotes, nor things present, nor things to come can separate me from the love of God in Christ Jesus.

I am not yet reconciled. I know I have a role to play in my own health and the health of the world. And yet, I can see God at work in Christ’s messy, visceral embodiment, and in my own.

Lucas Mix studies the intersection of biology, philosophy, and theology. A writer, speaker, professor, and Episcopalian priest, he has affiliations at Harvard , the Ronin Institute , and the Society of Ordained Scientists . He is currently studying long-term trends in biology with support from the John Templeton Foundation . Lucas blogs on faith, science and popular culture.