Speaking the truth in love (Eph. 4:15) may be one of the most misapplied biblical injunctions of our day. We use it to justify blunt commentary and harsh judgment, claiming a motive of love for God or the recipient. Too often, though, we’re just sidestepping kindness or humility. But what if we didn’t have to sacrifice one for the other? In Seasoned Speech: Rhetoric in the Life of the Church, James E. Beitler III shares a recipe for communication that’s persuasive, effective, and transformative. Persuasion podcast co-host Erin Straza spoke with Beitler about the power of rhetoric to bind our worship with our witness in a world that’s desperate for both.

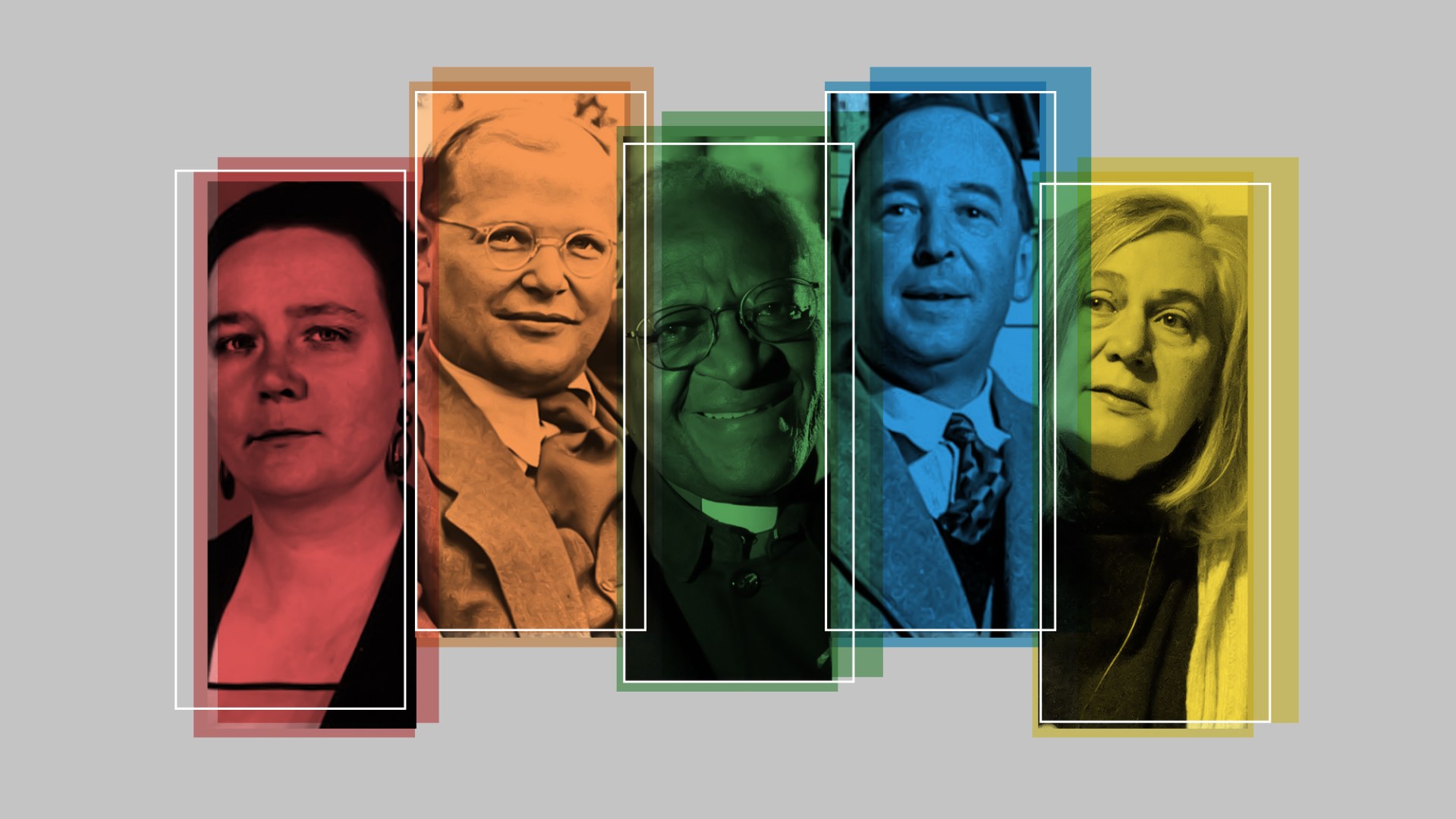

In the book, you identify the key communication skills of five renowned Christian thinkers (C.S. Lewis, Dorothy Sayers, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Desmond Tutu, and Marilynne Robinson), and you match them with the church’s liturgical calendar. How does the book’s structure help us see connections between the rhetoric of worship and witness?

We are in a moment that’s seeing a renewed interest in liturgy. Thanks in part to the work of James K. A. Smith and others, I began thinking about the ways in which liturgy involves not just spiritual formation and virtue but also our witness. My hope is to prompt readers to think about the ways in which their own worship practices, their own participation in the life of the church, can shape their own forms of witness. How can we present the gospel in ways that are consistent with what we’re doing every Sunday?

In your introduction, you mention that being a master of rhetoric is not at odds to authentic Christian witness. Why is this a common concern?

The word rhetoric is often used pejoratively. There’s skepticism about what rhetoric is. We assume it’s a form of manipulation that’s inherently opposed to truth-seeking. But rhetoric is unavoidable: One way or another, we’re always employing rhetoric when we communicate. We are positioning ourselves in particular ways. We are making a plea to particular values or emotions.

If rhetoric is unavoidable, the question becomes, How should we use it? Augustine realized this and basically said, “Since rhetoric is used to promote what’s false, we should instead employ it to support what’s true.” By thinking of it in pejorative ways—or by not thinking about it enough—we’re hampering our witness. There’s this rich tradition we can draw on for communicating effectively.

Few of us can escape the torrent of heated opinion and commentary on the world’s issues—in the news, on our social feeds, in our conversational circles. What do you see as an effective response from people of faith and the church at large?

One of the most important responses is opening up spaces for active listening. That’s something that I found C.S. Lewis did particularly well. Lewis had this posture of goodwill toward those around him—toward friends and students, but also toward people he didn’t agree with, including non-believers.

Also, we have too few spaces right now where dialogue across differing viewpoints can happen. Figures like Marilynne Robinson are incredibly useful in addressing this. Her stories are realistic about the difficulties of belonging, as they’re inhabited by people with very different beliefs. Yet she makes a welcoming space for readers. There’s an important moment in her novel Home when two characters, a father and son (Robert and Jack Boughton) who have a very tense relationship, are watching the news. Jack sees the violence happening in the South, and he exclaims, “Jesus Christ!” And his dad, who was a minister, reacts instead to Jack’s taking the Lord’s name in vain. On one hand, you have this figure who is very much concerned with social justice. On the other, you have someone very much concerned with truth and holiness.

It’s so valuable when the church has places where commitments both to truth and justice are radically affirmed. Robinson’s book points to an ideal of restoration, of harmony—what the biblical writers would call shalom.

The chapter “Professing the Creeds” features Dorothy Sayers, whose creative works confronted people with the person of Jesus Christ in uncommon and arresting ways. How can her work help make us more effective and powerful in sharing the gospel?

Sayers was very tentative about expressing her personal vows. The force of the gospel’s proclamation, for her, came first through the profession of the creeds and second through one’s profession, in terms of work or vocation.

In her writings, she sought to portray the gospel as vividly as possible. Whether we’re writing plays, preaching, or just talking to other people, our witness is not just about argument and exposition but also about description and narration. Through vivid depiction, Sayers showed the glory of Christ and him crucified. We all should strive to make this story visible. And another lesson from Sayers: Do it with humility.

Another chapter, “Calling for Repentance,” draws parallels between Desmond Tutu’s anti-apartheid work and the rhetoric of Lenten confession. What lessons can the church learn in modeling repentance and calling others to it as well?

This chapter draws on Jennifer McBride’s wonderful book The Church for the World. She proposes that the crucial posture for the church to adopt in society is the confession of sin. The force and persuasiveness of our message lies in embodying Christ’s reconciling love, and that’s where Desmond Tutu comes in. He’s an exemplar of calling for repentance, truth-telling, and forgiveness. And his rhetoric is grounded in how we’re all interconnected: My humanity is wrapped up and enmeshed with your humanity. So what diminishes one diminishes all; what builds up one builds up all. Such notions were incredibly important for Tutu during the truth and reconciliation process in South Africa.

If the church models repentance, reconciliation, and forgiveness, I think it will lead in profound ways. This isn’t the kind of leadership that we see from many of our political leaders right now. That model of leadership is based on protecting myself. I’m right; if I’m accused, I will deny. The church is called to model a different approach.

Some people seem naturally skilled in effective persuasion. But many others feel nervous about entering conversations on hot-button topics. What do you recommend for those who don’t feel quite as gifted?

Rhetorical effectiveness comes with practice. The ancient rhetoricians knew this, so they gave their students ample training. Students went through different exercises to learn effective communicating, including imitation. That didn’t just mean copying what others had said before. It was a much more robust notion of drawing on the past as a resource for invention.

One way people can improve is by reading and listening to people who are effective at persuasion and communication. You don’t have to be C.S. Lewis to show goodwill to opponents. You don’t have to be Dietrich Bonhoeffer to identify with those in need. And you don’t have to write like Marilynne Robinson to use language in hospitable ways. Rhetorical mastery isn’t the ultimate goal; rather, we should aspire to faithful rhetorical practice. The point is not merely to copy what Lewis, Sayers, Bonhoeffer, Tutu, or Robinson are doing. Instead, I want to see us reflect on our own practices and gifts and then, working through vocation or place, cultivate those gifts. All of us can learn how to communicate the gospel more effectively in our own particular ways.

Learn something new from this interview? Did we miss something? Let us know here.