When one of the world’s top Greek scholars at a top university spread “first and second century” New Testament manuscripts on top of his office pool table, my colleague and I about fainted.

Surrounded by classical busts, Egyptian funerary masks, and a pile of medieval binder fragments, we stood mesmerized in the office of Dirk Obbink at Christ Church, Oxford. The “First-Century Mark” saga began. It’s still playing out.

Over the last eight years, we learned that much was not as it seemed. There seemed to be a manuscript fragment of a gospel dating to the first decades of the church. Not quite. The manuscript seemed to be for sale. It wasn’t, really. Now the world knows there were four early gospel fragments “for sale,” and at the helm was an esteemed professor, transitioning these days into a sort of Sir Leigh Teabing of Da Vinci Code lore.

Like the Harry Potter “moving staircase” at Hogwarts, filmed across in the Bodley Tower viewable from Obbink’s window, what was to unfold over the next several years would seem illusory for outside scholars and became sensationalized in the press. The sudden appearance of these manuscripts was dizzying even for the experts and owners, temporary and otherwise.

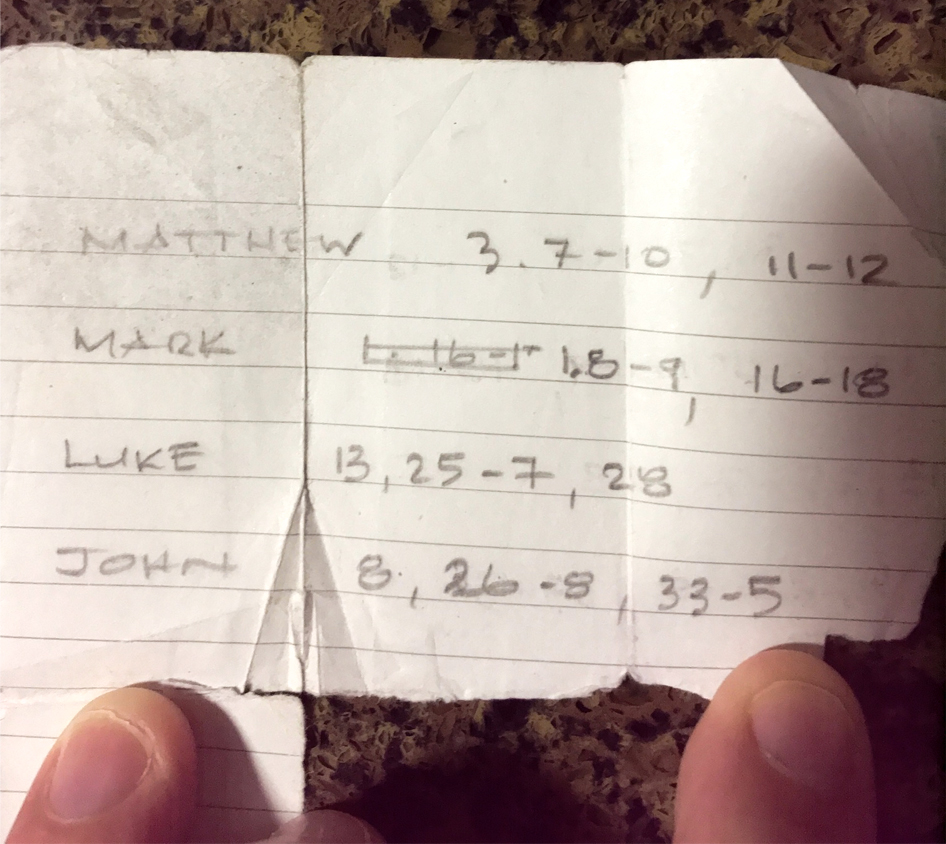

Scott Carroll and I, the two founding scholars for the Museum of the Bible, were there—we thought—for another research discussion. These were always enjoyable though long visits. As we were about to leave Obbink’s office, he stood and said, “I have something you two might like to see.” He pulled out a manila filing envelope and opened Pandora’s Box. He showed us four papyrus pieces of New Testament Gospels identified as Matthew 3:7–10, 11–12; Mark 1:8–9, 16–18; Luke 13: 25–27, 28; and John 8:26–28, 33-35.

Obbink said that three of the pieces dated from the second century (AD 100–200). Then he pointed to key letter markings in the Mark fragment: the epsilon (e), upsilon (u), and tau (t). He was convinced, he said, that it was extremely early: “very likely first century.” Even the famed “John Ryland’s Papyrus,” considered by most to be the earliest known piece of the New Testament, is usually dated to the early or middle second century.

On that eventful evening in 2011, Carroll became ecstatic. Veins along his neck bulged. He paced with arms flailing. What Bible scholar wouldn’t be excited? After all, Obbink is a MacArthur Genius Award recipient and was head of the famed Oxyrhynchus collection. He knows his stuff—flat-out brilliant. At one point, he had appointments both at the University of Michigan and Christ Church, then simultaneously with Oxford and Baylor University. And, he was always a gentleman and great with students. A master teacher.

Eventually, all four pieces were purchased in 2013 for a considerable sum—though at a fraction of their value (even taking the later dates our researchers suggested).

For context on the rarity of these remarkable texts, the esteemed David C. Parker of the University of Birmingham lists only five New Testament pieces in the second century. Dan Wallace, founder of the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts, claims there are minimally four second-century Gospel fragments, and maximally 13—counting Obbink’s Mark fragment and those on the third-century edge. In short, they are extremely rare.

Scott Carroll and I had met professor Dirk Obbink many times in his Christ Church office in Oxford, had traveled with him, shared high table at Christ Church, and had invited him to be a senior fellow for the Museum of the Bible. Carroll and I had traveled a long but intermittent journey together. In the 1980s we both studied under the eminent ancient historian and Bible scholar Edwin Yamauchi. In the 1990s, we had helped financier Robert Van Kampen build his Bible collection (now at the heart of the Holy Land Experience in Orlando). Later, we worked to launch the Museum of the Bible, along with Steve Green (president of Hobby Lobby).

Through the decades, we handled thousands of ancient manuscripts in various parts of the world; had helped host exhibits in the Vatican; met in the manuscript bowels of Monte Casino; stayed in the Coptic papal residence in Wadi Natrun, Egypt; stood on a Persian rug in a bomb shelter covering a trove of antiquities in Jerusalem; had residence in Hampton Court, Herefordshire; watched Gordy Young blow a sulfate compound through scientific tubing onto cuneiform in Michigan; hosted a special evening session at the old British Library; and planned countless sessions and workshops with brilliant men and women on biblical texts.

We were approached by dealers and reporters in the oddest of ways, like the dinner at the iconic Cattleman’s restaurant in Oklahoma City. In 2010, after eating with Warren and Beverly Van Kampen, a dealer unexpectedly appeared at Carroll’s Cadillac (a gift from Bob Van Kampen for giving a brilliant answer to a spontaneous Bible question). He startled us. Nonetheless, with some bravado he placed a large open box of ancient books on the trunk, and when Carroll refused him, he left them anyway (some appeared to be rare incunables). He yelled through the parking lot, “There are descriptions in the folder. You’ll love these. Call me!”

Others had inherited or were gifted rare items of immense value. After speaking at Liberty University, I went to shake a fellow’s hand at the end of the greeting line. Instead, he pulled out a paper tube from beneath his trench coat and tried to show me a Megillah (Esther scroll) he wanted to sell. After speaking in Springfield, Missouri, a senator brought an impressive early Victorian Bible for insights; it was large enough for a shopping cart. One fellow kept calling about a buried boxcar of antiquities in Texas, another claiming ownership of something from Jesus’ birth stable, and yet another with plaster casts of the first-century tomb in Jerusalem. Of course, once I ask to see the Israeli Antiquities Authority documentation, the conversations usually change. Perhaps the most memorable incident was in Grand Haven when a brother and sister around retirement age realized one of the Bibles in our display was the same as the one they had buried with their Dutch mother. When they learned that one had sold at auction for over $200,000, the brother turned to his sister and said, “Well, I guess we’re just gonna hav’ to dig ’er up.”

Against this backdrop of the wild ride in the antiquities world, one in which many of the greatest museums have been snookered by forgeries or authentic items with forged documents, we recruited numerous top experts in various fields, including Dirk Obbink. Then he showed us what appeared to be one of the greatest discoveries since Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt had excavated the bonanza of papyri in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, in the late 1800s.

The “First-Century Mark” fragment enthused Carroll, and rightfully so. But this gifted communicator with a rare streak of creativity fell victim to his own excitement. He prematurely informed Wallace that it was okay to announce it during his debate with leading atheist scholar Bart Ehrman in February 2012. The announcement went viral—at least in the world of biblical literature scholars. Wallace says he and Carroll met the night before the debate and that Carroll showed him additional Greek manuscripts—but not the four we had seen in Oxford. (Ten of the Museum of the Bible’s New Testament papyri are currently with various research groups.) Days after the Wallace debate, long before the finalized “sale” of the four papyri, Carroll left the museum to start the Manuscript Research Group, which appears to keep rather busy. Due to some pending non-disclosures on his end, we didn’t talk again for seven years.

Even though it was the star scholar Obbink who was involved (he said he was selling the manuscripts on behalf of a private collection—a common practice), the funder from Hobby Lobby agreed to maintain our due diligence, so I consulted further expert opinion. As is well known, I recruited Wallace, who also serves as professor at Dallas Theological Seminary. Neither he nor anyone else was willing to vouch with any confidence for a pre-second century date on any of the pieces. One told me I should consult with Dirk Obbink, since he is “the established expert on papyri of this kind.” Well, yes. Peter Head, then at Tyndale House, Cambridge, candidly noted keeping “among the earliest” New Testament pieces confidential would be difficult—candor I appreciated. Since nondisclosure was a non-negotiable from Obbink (allegedly on the part of the owners), Head and I mutually agreed not to have him involved. The other scholars sat with me at different times and places and studied the four images from my laptop (another condition).

Remember when I said that the manuscripts were one of the greatest discoveries since Grenfell and Hunt had excavated the Oxyrhynchus papyri? Well, it turned out that they were part of the discovery that Grenfell and Hunt made. As news of a “First-Century Mark” surfaced, it eventually became obvious it was a piece in the Oxyrhynchus collection (P.Oxy. 83.5345; P137)—which, at the time, was under Obbink’s purview in Oxford. The piece had been awaiting research for a century, and cryptically identified in the 1980s as early New Testament (though not as Mark). When the Egyptian Exploration Society (EES), who owns this collection, discovered it was the same piece in the news, it logically thought the piece had never been for sale nor had it ever been out of its possession.

Before the EES became aware of this particular case, that the “First-Century Mark” was actually its own, Obbink reported to Steve Green (chair of the Museum of the Bible’s board) and me that the EES gave him an ultimatum to sever all public ties with our museum or be fired. His name had started surfacing in connection with other rare pieces and our museum, like the Sappho manuscripts he published, and the contract with Brill Publishers for a series. I invited him to the contract signing in Leiden and he appeared in their press release photo with our museum representatives. The sheer volume of all these new texts was raising concern. We happened to be in Oxford on the day of Obbink’s fateful meeting with the EES in London, and upon his return we sat long into the night on the patio of Oxford’s Cotswold Lodge Hotel listening to this distraught esteemed scholar. He was facing a reality that neither the EES nor we fully understood, nor could we until later—he evidently was playing both ends against the middle. . That’s how people get squashed. We simply didn’t understand the animosity.

I confided in Peter Williams, warden of Tyndale House, Cambridge, and even discussed arranging a meeting with the eminent Kenneth Kitchen and his EES colleagues to understand more fully the situation. I put forth an internal proposal to fund a professorship in Kitchen’s name at Christ Church, should the progenitor agree, assuming that Dirk would not accept the EES’s conditions. But he did, and I was outvoted anyway in favor of a plan in Waco, Texas. The meeting with Kitchen never took place, and Obbink’s dual role at Baylor began. Keep in mind: Obbink was the heralded scholar in his field, a papyrology rock star if you will. And rather enjoyable. This was an amazing catch for Baylor.

But on the “First-Century Mark” front, I could only scratch my head in disbelief, and scratch off years from the calendar as the First-Century Mark seemed mysteriously evasive. Besides questions on how Obbink, a professor, could afford to buy the Cottonland Castle in Waco, he appeared to be yet another gifted scholar helping wealthy families with their collections, and in no hurry. After all, the Oxyrhnchus project he headed was into its second century.

However, the story took a curious and fateful twist during a rather serendipitous (or Providential) dinner with Edwin Yamauchi. It proved fortuitous.

It wasn’t until November 2017 that I realized a serious ethical breach had occurred, either by Obbink, a collector he was representing, or both. Though frustrated about Obbink’s silence on the research (he assigned me to write the historical background on Mark studies for its publication), I had learned to respect his timing—he rarely rushes scholarship. Other scholars had taken over the Brill manuscript series I had begun, I had a full plate, and I was recovering from a quadruple bypass.

However, I discovered a cover-up was in the making. While sitting with Yamauchi at the opening gala dinner at the Museum of the Bible, this whole affair began to unravel. Yamauchi asked a simple question of David Trobisch, then curator of the Museum’s collection: “Dr. Trobisch, Scott Carroll mentioned the first-century Mark fragment. When do you expect its publication?” Trobisch responded, “That fragment was never offered to us for sale, isn’t that correct, Jerry?” I about snorted coffee through my nose, then responded, “Some things are best discussed in other settings.” Then David continued, “A researcher in Oxford, I think a graduate student, discovered an image of it in a museum collection, and it has remained there. It was just a misunderstanding.” You could have hit me with a frozen salmon. Apparently Obbink, or his alleged collectors, were unaware of filmed evidence of this rare piece—dating to the 1980s and rediscovered in 2008! Or someone stole it and just thought the chances of going undetected were worth it.

Photo by Jerry Pattengale

Photo by Jerry PattengaleAfter taking a picture of my dinner guests, as I often do, I excused myself and immediately sent a message to the funder and museum leadership outlining the seriousness of what had transpired. The law of non-contradiction comes into play here. I had worked closely with Obbink, at his request, to ensure conditions of the contract (promising no publicity until its publication). Now I realize we had all been misguided by a genius. Roberta Mazza, Josephine Dru, Candida Moss, Brent Nongbri, Ariel Sabar, and the host of scholars associated with Tyndale House Cambridge had been asking important questions, and finally some answers were no longer opaque.

Last week, with enough evidence now to go public, Michael Holmes (noted for his edition of the Apostolic Fathers and my replacement several years ago at the museum over the research side), released a copy of the purchase agreement signed by Obbink. He also included Obbink’s handwritten list of the manuscripts, a folded paper that I carried for years in my wallet. As this goes to press, an Oxford scholar informed me he traced the unidentified picture Holmes released to my house in Indiana using iPhone metadata. He knows what iPhone I used and when it was taken. I sent the picture to the museum for its files before my retirement, realizing it might be a helpful artifact in this case. Many of my digital files and most photos were lost after a malicious ransom locker virus fried my computer. After I published “How the Jesus Wife Hoax Fell Apart” (Wall Street Journal, 5.14.2014), Obbink and others thought I was drawing too much attention to their work, indirectly. The relentless attacks on me, real or perceived, are too many to record here. But after the dinner with Yamauchi, I understood the real reason for the nondisclosure request.

Photo by Jerry Pattengale

Photo by Jerry PattengaleThe extent of Obbink’s involvement in other sales is yet to unfold.

The greater the mind, the chance for the greater error—and that’s exactly what has transpired here. I have remained silent for eight years on this transaction, for the first several because the buyers agreed not to publicize or sensationalize in any way this research. Then, I remained silent after reporting this matter so it could be handled by authorities. Jeff Kloha and Trobisch (both over curatorial programs at the museum at the time) were immediately sent to the UK to meet with Obbink, and the journey to this week’s release began. What we still don’t know, as Moss hints in her Daily Beast article this week, is whether Obbink was himself deceived by a collector who obtained items sometime after the photograph notes in the 1980s. This is certainly not without precedent, like the case at Drew University in which an 18-year old freshman stole over 30 letters from the John and Charles Wesley collection. He had only worked as an intern in the archives for six months in 2010. In this case, we are reminded that many dealers have the highest of standards—a dealer in England reported the Wesley items. In the Mark case, at the least, the items were under Obbink’s purview and some bold misstatements were made.

Perhaps Obbink’s actions prompted something that may not have happened in any of our lifetimes—the prioritizing of the biblical texts, especially the Mark fragment, among the items to be researched in the massive Oxyrhynchus collection. As Elijah Hixson noted in his publication, it’s not first-century, but it’s still the earliest piece of Mark ever discovered.

Scholars have been working on this Oxyrhynchus collection for over a hundred years, and over 40 percent (more than 50 items) of all early New Testament fragments come from this collection. Tommy Wasserman of Örebro Theological Seminary in Sweden shared recently in his seminar in Oxford that currently over 30 unpublished New Testament papyri are being studied in research groups throughout the world. One of Obbink’s lasting legacies will likely be the digitization of this collection, which transforms accessibility.

A flood of biblical texts became available during the last couple of decades, some allegedly through cartonnage (think ancient papier-mâché made of discarded manuscripts). Obbink and Carroll held various public demonstrations of this practice. Some were educational, like Obbink’s lecture, “Preservation of the Painted Surface in Cartonnage Extraction” (Catholic Chaplaincy, St. Aldate’s, Oxford 7.9.14). Some were filmed. Though nearly all such texts recovered are secular, the (rather old) practice heightened interest in excavating ancient trash within trash. (The price of cartonnage has heightened quite a bit as well.) Obbink asked me to assist on occasion. I once saw about a foot-high stack of texts taken out of cartonnage—of inestimable value for understanding the third through sixth centuries. One YouTube video created quite a stir, provoking questions of cultural heritage insensitivities and celebrity involvement.

Dealers, including Obbink, learned early in the history of Museum of the Bible that there are Christians with tremendous financial means that love the Bible. But it is what he and others learned next, coupled with this new financial support, that is wreaking havoc on their old practices: A new host of Bible lovers (Christian and otherwise) have been amassed with remarkable language and research skills. Like martyrs throughout the centuries, many are aggressively dedicating their lives to its study out of religious duty. One might take advantage of them, like dealers have done for centuries, but the risk is greater; now a large group of gifted text and historical scholars has a dogged interest in every detail. From tracking textual variants to GPS records on iPhone images, these are serious efforts of scholarship. And perhaps Holmes’s posting of the contract will also help establish more collaborative efforts between the diverse groups at the Society of Biblical Literature, and with other important bodies like the EES.

I was fortunate, truly honored, to found the Scholars Program at the museum (originally called the Green Scholars Initiative), and at the start recruited over 20 of the world’s leading scholars as fellows. Scholarly involvement continues to grow under new leadership. From those mentioned to the likes of Christian Askeland, Abson Joseph, Elaine Bernius, Dirk Jongkind, Bobby Duke, Catherine McDowell, Stanley Rosenberg, Tim Laniak, David Riggs, Martin Heide, and a host of other scholars and mentors, biblical and church history studies have a healthy future.

Through this program, hundreds of biblical studies students had special access to text studies, and over 200 won scholarships to study in Oxford in the Logos program (an option for those seeking to understand how their faith intersects with their academic careers in biblical text studies). Many of these students have already finished major degrees. Nine recipients of the Edwin M. Yamauchi Award received support for PhDs in biblical text studies—from schools ranging from Notre Dame and Edinburgh to Cambridge, Oxford, and UCLA. One of the biggest surprises is that the main funders, the Green family, continue to give at a remarkable level even in the midst of an avalanche of criticism, with the harshest being either ad hominem or political. I could write a book on what I’ve observed. But for them, they have one central Book which maps their arduous journey.

Yes, the “First-Century Mark” fragment “sale” was scandalous. But huge developments in the biblical text studies fields give us hope. Bright young Christian scholars are at the proverbial table for the next generation, working alongside similarly gifted scholars of various faiths, or no faith at all. As optimistic as I am, I am even more cautious. Once again, even surrounded by many of the world’s best scholars, evangelicals, including me, fell for another “first-century” manuscript. Each biblical scholar answers questions about authenticity, accuracy, and authority. The scholars involved in this story have spent countless hours on the first two questions about manuscripts like “First-Century Mark.” But many of them, like myself, ultimately hold the last one, the question of the Bible’s authority in our lives, the most important. In truth, all three are linked—and centuries of these studies, though at times bizarre and frustrating, only strengthen our trust in the text’s historicity itself. In this case, when the smoke clears, the earliest piece of Mark’s gospel has resurfaced and we were alive to see it, plucked from an Egyptian dump a century ago, and it still reads the same.

After eight years, there is some relief in finally weighing in. Perhaps to take a break I will catch up on that Fixer Upper show with Chip and Joanna Gaines. I hear they purchased the Cottonland Castle.

Jerry Pattengale is University Professor at Indiana Wesleyan University and author, most recently, of Is the Bible at Fault? He served the Museum of the Bible from 2010 until retiring as executive director of education in December 2018. He also holds various distinguished appointments, serves on the boards of Religion News Service and Jonathan Edwards’ Center (Yale), and is associate publisher of Christian Scholar’s Review. He redirected all of his stipend to charity.