In this series

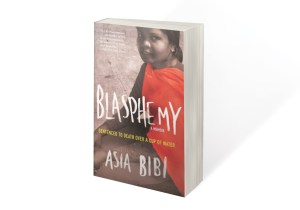

Christians breathed a sigh of relief last October when Pakistan’s Supreme Court acquitted Asia Bibi, a Christian mother of five on death row, of blasphemy charges against Islam. What many might not have noticed was the Islamic rationale.

Whether or not she spoke against Muhammad, Bibi was insulted first as a Christian, wrote the judge. And on this, the Qur‘an is clear: Do not insult those that invoke other than Allah, lest they insult Allah in enmity without knowledge.

The verdict also quoted Islam’s prophet himself: “Whoever is cruel and hard on a non-Muslim minority, or curtails their rights … I will complain against the person on the Day of Judgment.”

And finally, it referenced an ancient treaty that Muhammad signed with the monks of Mount Sinai: “Christians are my citizens, and by God, I hold out against anything that displeases them.… No one of the Muslims is to disobey this covenant till the Last Day.”

Today it can seem like Muslims violate this covenant the world over. But does the Bibi decision validate those who insist that Islam rightly practiced is a religion of peace? And should Christians join Muslims to share verses that comprise the Islamic case for religious freedom?

CT surveyed more than a dozen evangelical experts engaged with Muslims or scholarship on Islam who reflected on three key questions when considering interpretations of Islam that favor religious freedom.

Is It True?

Pakistan’s verdict relied on three sources that inform Islam: the Qur‘an, the Hadith, and covenants.

The Qur‘an is the foundational text, considered to be dictated by Allah. The traditions, or Hadith, were collected by men, are subject to critical review, and have become widely accepted as authoritative. The covenants are part of the Sunna, the practices of Muhammad, and are debated. (While Islam’s prophet did enter into treaties with Christian communities, some texts are less known to Muslims, so they may have been composed later by Christian groups angling for better treatment.)

“Our primary concern should be to uncover the truth about these narratives,” said Harold Netland, professor at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and author of Christianity and Religious Diversity. “We want to know as much as we can about what Muhammad actually was like, as well as the relations between Christians and early Muslims.”

David Johnston, a University of Pennsylvania visiting professor who ministered for 16 years in the Arab world, points to Islamic resources that “undergird a solid theology of democracy and human rights.” “Most Muslims, especially in the West, want to highlight this,” he said.

But other Christians are concerned that Islamic texts and traditions don’t look favorably on non-Muslims.

“Islam has this internal tension between its claim to be generous and tolerant, and its own manifest intolerance,” said Mark Durie, an Australian pastor whose book, The Third Choice, features his research into the status of minority faiths following the Islamic conquests. The covenants, Durie believes, were a survival strategy and “proof of bondage.”

“Muslims, like Christians, adopt very flexible interpretive strategies,” said David Vishanoff, who sees plenty in Islam to accommodate Christian minorities—or to persecute them. “It is their lived experience of interaction with Christians, or the lack thereof, that will determine their understanding of the Qur‘an and Hadith, not the other way around,” according to the University of Oklahoma religious studies professor.

So are these conciliatory passages true Islam? Perhaps authenticity isn’t important. “What matters is what Muslims today find inspiring and useful,” Vishanoff said.

Is It Helpful?

“Anything that helps one wrestle with our hard-wired yearning to be in relationship with our Creator and each other is a good thing,” said Chris Seiple, president emeritus of the Institute for Global Engagement, “even if not true, or non-Christian, like a secular novel.”

If done in good will, relationships develop and ears open, he said. The Holy Spirit will blow where he wills.

Many evangelicals see sharing the good in Islam as a way to love their neighbors. “We have a responsibility to give the best, most honest account of another religious tradition that we can,” said Sara Shady, coauthor of From Bubble to Bridge: Educating Christians for a Multifaith World.

The results can be transformative. She referenced the work of Eboo Patel, Muslim president of Interfaith Youth Core, and how his mastery of Christian traditions helped her better see her own Christian faith.

This is true even in the Middle East, said Salim Munayer, head of the Musalaha reconciliation ministry in Jerusalem. But there is another step.

The positive teachings of Islam can be a tool to challenge the mistreatment of Christians, he said. But Christians must be mindful that Muslims are in a deep period of reflection following the twin shocks of the Arab Spring and ISIS. Many feel their religion is under attack and respond with texts to show Islam is peaceful.

“This is good,” he said. “But it is our job to see this tolerance becomes part of the daily life of people.”

Is It Enough?

Others worry that the more militant verses in the Qur‘an ultimately outweigh and abrogate the more conciliatory passages, which were written earlier in Muhammad’s life.

“When Muslims of goodwill and courage choose to use materials from the Islamic tradition that are favorable to non-Muslims, as seems to have been done in the acquittal of Asia Bibi, it is a thing of beauty and must be warmly appreciated,” said Gordon Nickel, director of the Centre for Islamic Studies in Bangalore, India. “This does not make it the dominant interpretation, however.”

Even the Bibi verdict carries opposing messages regarding religious freedom since it also quotes the Qur‘an in support of the death penalty for blasphemy.

“Those who malign Allah and his Messenger, Allah hath cursed them in the world and the Hereafter,” the judge cited. Followed with application from another passage, “Then smite their necks.”

Andres Prins, a consultant with Eastern Mennonite Missions’ Christian-Muslim relations team, was jarred by the decision and unsure if the rationale represented sincere conviction or an attempt to appease the radicalized masses.

Still, asking Muslims to consider where their texts call for favorable treatment of other faiths can only help, he said. “Hopefully such God-conscious conversation will increasingly lead to the use of language and ideas in the public sphere that all the various religious and non-religious members of society can espouse and identify with.”

It already does, said Wissam al-Saliby, a Lebanese advocacy officer with the World Evangelical Alliance. Through his work with the United Nations, he noted how Muslim-majority countries are adept at international legal discourse and terminology. Other groups use Shari‘ah law to buttress women’s rights.

Nevertheless, Islamic jurisprudence and tradition are cited occasionally to justify reservations to international human rights law.

“So ideally, you have to use both,” he said. “We have to encourage our Muslim friends to take a stand and mediate with those on the ground.”

Religious language helps, and Prins’s colleague David Shenk provided an example. Speaking alongside UN experts at the Islamic University of Kosovo, he spoke on the image of God as man as a foundation for religious liberty, eventually enshrined in the fledgling nation’s constitution.

“We are the ‘people of the book’ who are to stand upon the scriptures that we possess,” Shenk said, using the title the Qur’an gives to Christians and Jews. “My gift to the team was a scriptural foundation for the freedom of humanity to choose.”

But will they? Can respectful dialogue about Islam open the door for Muslims to come to Christ? Several experts said that it becomes a possibility.

“Speaking the positive in Islam in no way denigrates our Christian witness or authority,” said Bob Roberts, a Southern Baptist megachurch pastor in Texas who is forging relationships with Muslims around the world. “Living in a world where all religions are now all places makes it incumbent upon us to no longer be lazy in discipleship.”

When Christians educate themselves, they show respect to Muslims and may gain a crucial ally, the NorthWood Church pastor said.

“These relationships have value,” Roberts said. “If not for their salvation, then for the protection of those that would follow Jesus or be persecuted for his sake.”

Jayson Casper is the Middle East correspondent for

Christianity Today

.This article has been updated from the version in the January/February 2019 magazine.

Have something to say about this topic? Let us know here.