You may have been told once or twice: “People can’t hear the gospel if they’re hungry.” I’ve read it dozens of times in statements from pastors in the United States. But where, exactly, does the idea come from?

Many pastors depend on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to decide how churches should minister—even though it’s been debunked.

The hierarchy of needs is a theory of human motivation, proposed in 1943 by psychologist Abraham Maslow, that says human beings have layers of needs: physiological, safety, belonging, esteem, and self-actualization, in that order. When people start to feel a certain need—say, the need for satisfaction in their jobs—it is because the lower layers of needs have been satisfied. Maslow put physiological needs at the bottom of his hierarchy, indicating that needs like air, water, food, sex, sleep, shelter, and clothing must be met before any other felt needs can arise and be addressed.

I learned about pastors’ dependence on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs while analyzing data collected by the Seed Company, on behalf of Barna Group. On a survey, senior pastors had written individual responses to explain their churches’ teaching about providing for physical and spiritual needs.

About one in six of the senior pastors, unprompted and in his or her own words, referred either specifically to Maslow’s hierarchy or to its main idea, that physical needs must be met before people experience spiritual needs.

People tend to say less than they could when answering free-response survey questions like this one. So if asked more specifically whether they agree that Maslow’s hierarchy is reliable, pastors, I expect, would be even more favorable toward it.

Outside of psychology, the theory has grown in mentions and in popularity since the 1960s. Google’s literature search, the Ngram Viewer, as well as its web search, Google Trends, show that Maslow’s idea is as popular as ever, if not more.

However, a group of psychologists who wanted to update the pyramid wrote in a 2010 Perspectives on Psychological Science article that “many behavioral scientists view Maslow’s pyramid as a quaint visual artifact without much contemporary theoretical importance.”

In truth, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs was never an accurate description of how people act, let alone a guide to discipleship. Yet if one in six senior pastors subscribes to its reasoning, then the theory has leavened the teaching in US churches.

Why is this such a big deal? Because when Christians go outside the Bible for ministry strategy, they should know if a source is reliable.

Neither Biblical nor Scientific

The hierarchy of needs theory is not so much scientific as speculative. Abraham Maslow first published his theory without empirical testing. He tweaked the theory throughout his career and kept things lively by publishing a list of people he thought had reached the pinnacle, self-actualization (many of whom he had never met, like George Washington). But he never did systematically compare the theory to real people’s behavior.

The theory is also problematic because it teaches us to coach others in the priorities of Esau, who gave up his birthright to appease stomach rumbles—hardly a biblical example of godliness. When he experienced deprivation, he lost all perspective, and not because that’s all a human is capable of.

Discipleship is, to a large extent, a matter of gaining perspective. For example, consider what life would be like if Maslow were correct that sex is a need that must be met before a person can aspire to ethical behavior. Getting consent, let alone marrying a willing person, would be too high an expectation for a Christian.

Similarly, the need for safety would precede the need to be reliable, so courage and truthfulness would be too much to expect from a person who didn’t feel safe—and wherever courage and truth are required, there’s risk.

If people feel no twinge of conscience, the theory goes, it’s probably because conscience hasn’t kicked in yet; they first need to be better off. But we live in a world where US slaves risked their lives to attend church and created beautiful spirituals that would enrich the world, when neither of the first two levels of their needs (physiological and safety) were met. Today, religion thrives in the poorest and most violent parts of the real world.

On a personal level, many of us have felt a simultaneous need both to pray and to sleep; to be polite and to chow down; to go to the bathroom and to finish a task.

Well-done social science can tell us if this sort of behavior is a pattern or an exception. Surprisingly few studies have directly tested the hierarchy of needs Maslow proposed in the 1940s. In 2011, however, Louis Tay and Ed Diener published an empirical study on the topic. They found that feeling a set of needs is not contingent on meeting other needs, Maslow’s main assertion. Instead, they showed, people around the world care about a jumble of “higher” and “lower” needs at the same time.

Another of Tay and Diener’s main findings made it even harder to express motivation and needs as a hierarchy. They found that each person’s well-being and satisfaction are linked to other people’s well-being and satisfaction.

What Need Really Does to Us

It’s not that physiological needs don’t change how people respond to spiritual things; they do. But Christians have differed wildly about how.

For some of the proponents of asceticism, such as Anthony of Egypt, satisfying the body would result in tamping down the needs of the soul. They might have thought Maslow’s hierarchy was not only upside-down but also that it should have expressed the idea of competitive rather than cumulative levels of needs.

The Desert Father Athanasius wrote admiringly of making life as uncomfortable as possible in his Life of Saint Anthony and asserted, “[T]he fibre of the soul is then sound when the pleasures of the body are diminished.”

Athanasius’ ascetic theology took from Jesus’ statement that the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak to prescribe a rigorous program of getting “the flesh” used to as much deprivation as possible. Followers of Maslow may well take the same verse to mean that the body must be satisfied. The results will be, according to each opposing prescription, the ability to focus on higher spiritual things.

So, what really happens?

We have some evidence of what deprivation, at the bottom of Maslow’s pyramid, can do. Some of the best insights we have into the spirituality of a starving person came from a study done at the end of World War II, meant to help restore concentration camp victims to health.

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment included 36 conscientious objectors, who were tracked as they followed a diet that made them look as wasted as the camp victims. In the guide based on the experiment, Men and Hunger, the researchers wrote, “Although fasting is said at times to quicken one spiritually, none of the men reported significant progress in their religious lives. Most of them felt that the semistarvation had coarsened rather than refined them, and they marveled at how thin their moral and social veneers seemed to be.”

One of the men who participated in the study wrote that he found himself “becoming senselessly irritable.” Participants and researchers realized that the hungry men became cranky, preoccupied, and obsessed with what they did not have.

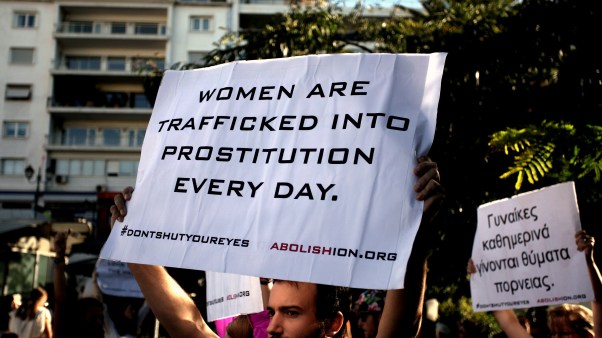

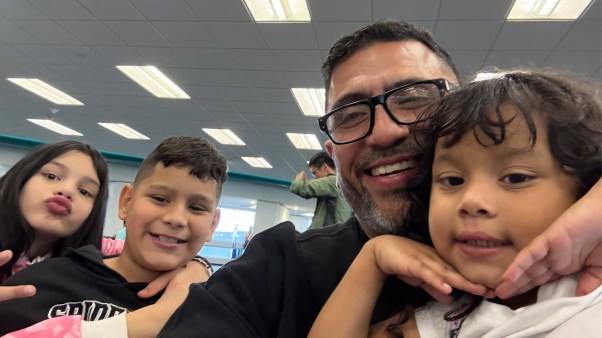

In Voices of the Poor, a World Bank project where poor people from around the world talked about their experiences, many mentioned feeling ashamed among colleagues, classmates, or even their families. A mother in Tanzania said, “How can you face your children day after day hungry?” The same report quoted a Ugandan man saying, “It is this feeling of helplessness that is so painful, more painful than poverty itself.”

So living with hunger, rather than reliably making people more spiritually focused, appears to deaden emotion and thinking, makes a person worse company, and can even make it difficult to be with loved ones. It’s hard to read about these experiences without wondering whether starvation doesn’t stunt the fruit of the Spirit—evidence for Maslow?

But Maslow’s original theory—the one that is usually taught—is that people do not feel a need for spirituality when they are hungry. In the real words of desperate people, they were frustrated by their own grumpiness, aware of their spiritual inadequacy, and still capable of starving for a higher good.

Poor people long for connection and meaning in a way Maslow did not perceive. Even the World Bank acknowledged that many poor people refer to God as the one who is able to rescue them.

In real-life ministry, the physically needy might still ignore or reject the gospel. We know it’s not because they lack the capacity, even if need can make everything—including spiritual life—a slog. Is it because of the way ministers are ministering? It could be.

If we want to minister effectively, we have information about what hurting people are receptive to. Again, the Starvation Experiment volunteers provide insight: They found “false heartiness” unendurable. They hated being pumped for information about how they were feeling. They resented feeling left out. They did not chuckle politely at corny jokes, though they did genuinely smirk at clever ones.

In Voices of the Poor, people longed for respect and courtesy, rather than suspicion. They wanted to have initiative and to be able to provide as fathers and mothers.

Scripture’s Answer to the Pyramid

It seems human needs cannot be expressed with a pyramid, but no new icon has replaced it yet. Is there a biblical perspective on the priority of human needs? Yes, but like much of Christian life, it is not a checklist of rules to follow. For example, Jesus didn’t establish a clear pattern of meeting physical or spiritual needs first, but practiced discernment in each case.

Over and over, the Bible says God’s people should not ignore poverty or suffering. Christians should respond to another’s needs as to a person God made by hand, whether we feel called to do that through organizations or in person. Emergency situations—such as getting a little kid fed through the most crucial months for brain development—are not very confusing. We should help save people’s lives. This is simply triage.

Even in non-crisis situations, we shouldn’t fight the urge to help by reasoning about the relative importance of eternal life. We don’t have to justify helping by thinking of people’s spiritual receptivity; compassion is a spiritually sound response (James 2:16).

How do we apply this to our own needs? Again, when we look at what Jesus said and did, we get advice that is less straightforward than we get from either Maslow or the ascetics, but advice that is more balanced.

On the non-ascetic side, Jesus promised an easy burden in contrast to the usual religiosity. He healed all the illnesses in a crowd (Matt. 12:15). He served good wine. He sent his Spirit, the Comforter. We do not have to be physically uncomfortable to follow Jesus.

Nor should we think that discomfort is a sign that something is spiritually wrong with us, that we lack faith, or that we must make relieving pain our top priority. Jesus blessed those who grieve and want better (Matt. 5:4–6). He challenged others—and himself—to ignore physical needs for limited times and spiritual purposes. He taught for three days before providing food to the 4,000 in Matthew 15. He fasted for 40 days and nights.

In the Seed Company study where so many pastors wrote in comments on Maslow, many others wrote that the physical and spiritual cannot be separated—or even distinguished—from each other. Isn’t contrasting spiritual and physical needs the sort of gnostic dualism we should avoid? they asked. Apparently not! It’s-all-the-same-ism isn’t a better understanding of people than dualism. Instead, it’s Esau’s error and today’s, as well.

Understanding this doesn’t require—and I won’t attempt to make—a list of which parts of a person are spirit and which are hormones, synapses, or anything else. To make things even more complicated, we know that which eating, drinking, and sleeping habits are spiritually damaging often depends on individual consciences and situations. However, there is a first step: to value spiritual life.

Jacob wasn’t right to offer Esau soup in exchange for a place in Christ’s genealogy. But Esau’s error was throwing a spiritual gift away as if it were used shrink wrap. It was not a fresh, modern rejection of dualism. Since Jesus warns us not to make spiritual tradeoffs in favor of our physical comfort (Mark 9:47), ministers should not encourage others to do the opposite. Nor should they fail to intervene during suffering or injustice.

One thing is sure: We can confidently expect people in all kinds of need to simultaneously need the God who heals; the God who forgives; the God who says, “Do not be afraid of what you are about to suffer”; and the God who does not allow hunger or danger to separate us from himself.

Susan Mettes is a CT editor at large. She has conducted research on topics such as decision-making in poverty and church life for Barna Group, the Gates Foundation, and other organizations. She now lives in Burundi with her husband.