When I was in Sunday school in third grade, my teacher seemed ancient. Each Sunday, with hair a bit askew, he’d pump our hands as we walked in the door because he was so glad to see us. We’d earn full-size Snickers bars for Bible memorization, and he’d take us on a fishing trip at the end of the year. His wife would sit down next to a tinny classroom piano, and we’d sing hymns at the close of each class.

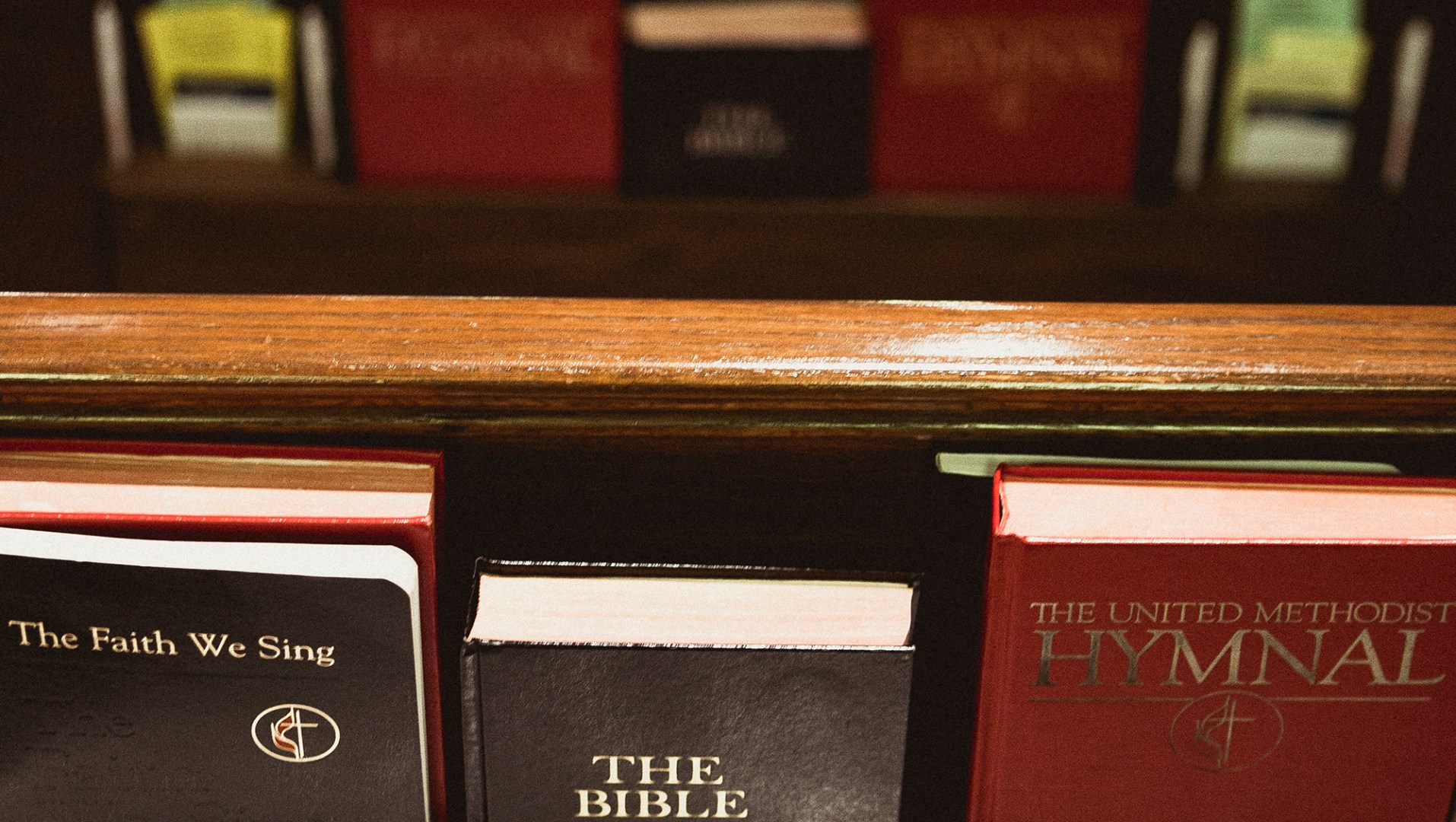

But the crowning glory of that year was receiving a hymnal of our very own, with gold embossed lettering, to continue our Christian education at home. It became a coveted object, one valued for its history. It signified our growing belonging to the church. Yet once in my possession, it simply sat atop the piano only my mother could play.

We are formed by the hymns and songs we sing. We are (perhaps more than we realize) formed, too, by the tangible objects of our faith. We are people of the book—not just people of the Word of God, but also people who have been corporately, theologically, devotionally, and socially formed by hymnbooks.

It is this history that Christopher N. Phillips artfully articulates in The Hymnal: A Reading History. This book is the only large-scale history and literary reading of hymnals, those “small companion[s]” that traveled with parishioners from church, home, and school. Phillips leads us like an artful detective through the early reading practices and religious life of the 18th and 19th centuries, in America and across the Atlantic.

Creating a Visible Identity

From our modern vantage point, perhaps we might see hymnals as outdated accessories of a worship service. But hymnbooks have served (and still may serve) a larger purpose. These books were the way children learned to read, the way illiterate congregants were able to apply a sermon, the way families instructed their children (and paved the way for children’s literature), the way poetic careers began, and the way that disparate individuals became the worshiping people of God.

Hymnbooks helped to bind the people of God together. Because “readers can be both individual and corporate,” writes Phillips, hymnbooks in worship nurtured the “achievement of corporate personhood.” For new religious groups or fringe groups (the ones Phillips examines are African Methodists, Reform Jews, and Latter-day Saints), hymnbooks were one of the first acts of creating a visible identity. For denominations, too, hymnbooks were used to wage war or create peace by what was included, what was excluded, and how the books were published and circulated.

Phillips traces the history of the genre and its use in three sacred spaces: the church, school, and home. Hymnbooks traveled with parishioners as personal devotional objects, aided in the emergence of the private self within a larger body (whether family or church), and even offered a handy tool for passing notes or disciplining children talking during a worship service. Hymnbooks were a sort of grocery sack for the growing American self—they held together different aspects of the experience of faith and provided familiar contours of religious and literary expression.

Phillips helps us see accomplished hymn writers like Isaac Watts, Charles Wesley, and William Cowper in the context of their times. More broadly, he reimagines for his Christian reader how the methods and practices of our reading form our loves and attention. It is not simply the content of hymns sung, read, gifted, or memorized that informs our thinking and spiritual appetites. The books themselves—and how they’re read, circulated, used, and travel—shape us. To put it quite simply, we are formed not only by what we read but by how (and with whom) we read.

Phillips reminds us that books have lives too, and for the modern-day reader, we must consider what we’ve lost personally and collectively by neglecting the hymnal as a tangible object. The Bible of course, like the hymnal, “straddle[s] the worlds of literary and religious reading, of song and private reflection.” But what is our experience of worship: Are we being formed in our bodies into the family of God? With the Bible on our phones and words on the screen in most evangelical churches, are we being molded into the church by the objects we touch, hold, and memorize? Or is it too easy to be a group of loosely networked individuals, where devotional practices and worship are experienced in an individualized manner?

Hymnbooks were so well-worn prior to 1820 that many haven’t survived—they were touched, held close, and their covers, spines, and bindings show what Phillips, quoting another scholar, calls “hand piety.” The hand piety we exhibit most often today manifests in sore pinkies from holding our phones and hunched backs from staring at screens. It might seem easy to harken back to a “golden age” of hymnals or pews, but for the time period Phillips chronicles, hymnbooks were innovative and divisive. Instead, believers today should begin to consider, through Phillips’s history, larger questions about how our reading informs us. After all, the form an object takes is never neutral: It always creates meaning.

And for those of us who read hymn and song lyrics projected onto screens each Sunday morning, have we lost something? If hymnbooks helped to form marginal groups into a people with a distinct identity, then what forms of corporate and private worship can bring us together as God’s people today?

The Furniture of Worshipping Christians

This summer, with my family, I visited a small mining town in Colorado without a single stoplight. Sunday morning, we stepped into the little stone Episcopal church off the main street. Though our own weekly Sunday liturgical practice is less formal than that of the church we visited, my children easily adapted to the readings and the prayers—because the words were familiar. The creeds, the hymns, and the Scripture readings aligned with what they knew church to be.

Yet, as I flipped between the Book of Common Prayer, the Bible, and the hymnal in the pew, I wondered what it would look like to be formed by books like these so thoroughly, so consistently. Would the prayers, hymns, and responsive readings grow repetitive and rote? Or would they create a texture and tapestry to faith that grew in resonance the more we returned to them? How would the weekly flipping of pages, with a “small brick of a book” (Phillips’s words) nestled in one’s palm, inform my spiritual practices? Would faith feel more solid with a book in my hand? These books, Phillips writes, were the “furniture of worshipping Christians” a century or two ago. What have we lost and what have we gained by trading out our furniture?

For those of us today who are apt to pick up our phones as a source of “virtual community,” The Hymnaltells an important story: a story of formation by books, traced through families and religious groups and across racial, socio-economic, and national lines. It’s a story I hope will help us to begin to recover our sense of being spiritually formed people—as families and as the family of God from every tribe, tongue, and nation.

Ashley Hales is a writer living in Southern California. She is the author of a forthcoming book, Finding Holy in the Suburbs: Living Faithfully in the Land of Too Much (InterVarsity Press).