“As a Christian at university, I was faced with a hierarchy of possibilities. The really holy people became missionaries, the rather holy people were ordained, and the fairly holy people became teachers; the ‘also rans’ did all the other jobs in the world,” so wrote R. J. Berry in his book Real Science, Real Faith. Having discovered that he either couldn’t or shouldn’t do any of the “holy” jobs, Berry, known to most as Sam, eventually realized “that we have all been given different talents and callings, and that there is not (and should not be) such a thing as a typical or normal Christian.”

Sam Berry was anything but a normal Christian. He attended his local church regularly, went to the monthly prayer meetings whenever he could, and served on the church council. For the last 30 years of his life he was licensed to preach, and for about 20 years he took part in national synod meetings. This would have been a huge commitment on top of a regular job and raising three children, but Sam was a high-capacity person who was not content to conform to the stereotype of “also-ran”—those who run races but never win. He demonstrated to the best of his ability that every single Christian is in full-time ministry.

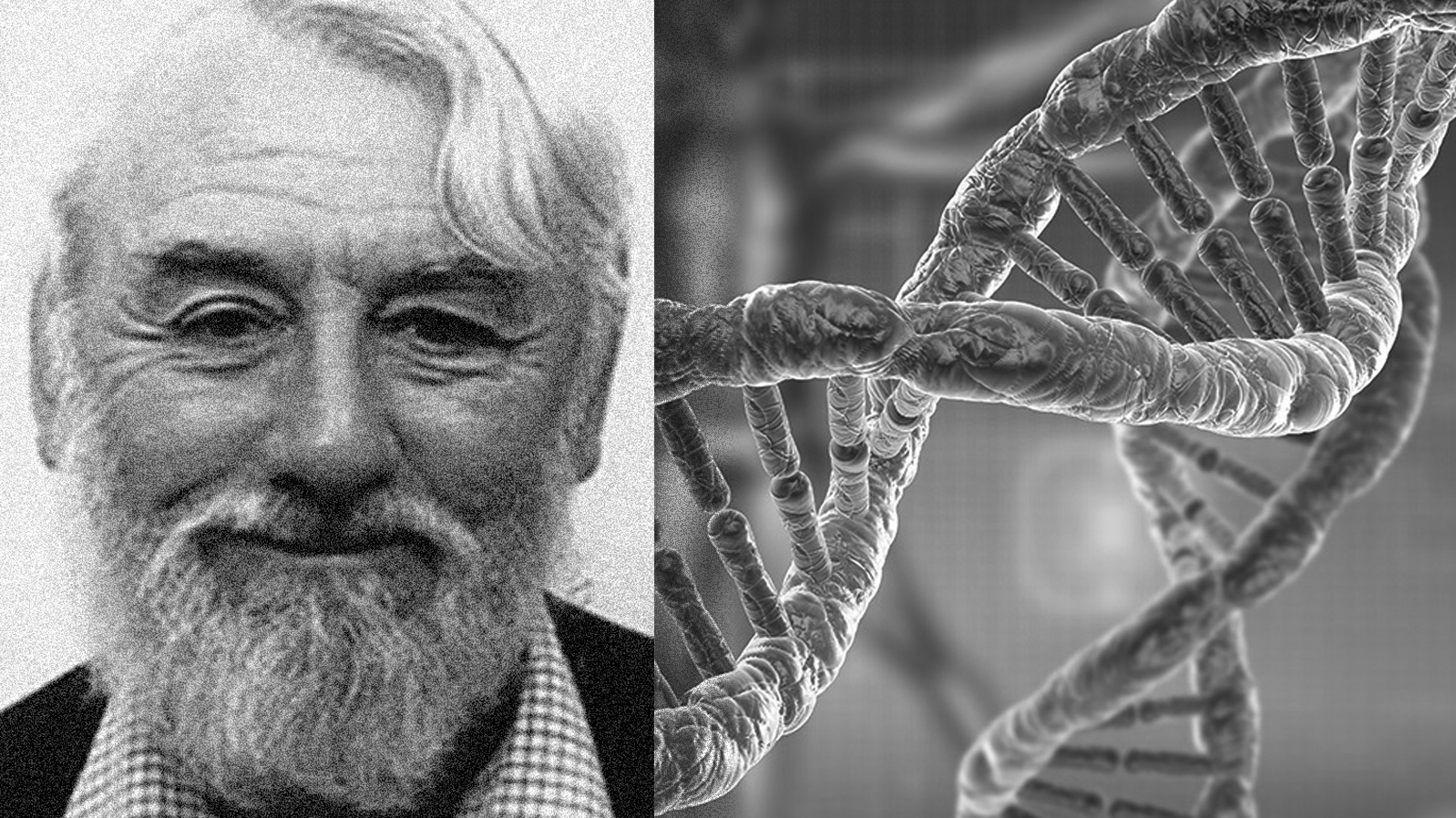

As professor of genetics at University College London, Sam studied island populations (especially mice), which often involved field trips to remote Scottish islands. He was a distinguished biologist and published work on evolutionary and ecological genetics, biodiversity, and conservation biology, and was the president of several prestigious scientific societies. His final academic contribution, a book titled Environmental Attitudes Through Time was published this month by Cambridge University Press, just a few weeks after his death at the age of 84. I attended the service of thanksgiving for his life, which included a tribute from his colleague Professor Steve Jones—himself a renowned biologist and communicator. Jones’s contribution was all the more remarkable because he is well-known for his rejection of faith yet was able to celebrate such a well-known Christian’s scientific achievements and recognize that he had “gone to a better place.”

Another hang-up for Sam as a student had been the pressure to share his faith in a particular way. Realizing that he “had none of the gifts possessed by some of getting alongside people and proclaiming Christ,” he recognized that this was “not an excuse to avoid living and speaking for Christ at every available opportunity.” One of the ways he did this was by thinking deeply about how science and faith can work together: speaking, writing, and editing books on the subject.

His first science-faith book was on the compatibility of evolutionary biology and the Genesis story. This has been a difficult and sometimes painful question for many biologists in evangelical churches, and Sam’s first book Adam and the Ape in 1975 helped many people to think through the issues. In his 2007 Faraday paper Creation and Evolution Not Creation or Evolution he wrote, “When we put together faith and reason, we can join with the whole creation in praising our maker and redeemer, and rejoice in the wholeness which is the true end of humanity. We do not have to choose between evolution or creation; biblical faith leads us to affirming both.”

The question of miracles can also be a tricky one for scientists, and when there was controversy over a senior bishop in the Church of England rejecting certain miracles, Sam stepped in. His 1984 letter to the Times, signed by 13 other senior scientists and academics, stated, “It is not logically valid to use science as an argument against miracles. To believe that miracles cannot happen is as much an act of faith as to believe that they can.” This stirred up a hornet's nest of debate in the scientific community that ran over multiple issues of the journal Nature. I am personally glad that such a senior scientist was willing to nail his colors to the mast so clearly.

When he “retired,” the majority of Sam’s energy was devoted to caring for creation. He was one of a generation who realized that we will face serious problems if we fail to rein in our consumption of natural resources. Drawing on his experience as a geneticist and a naturalist, he became one of the founders of the UK Christian environmental movement. I remember his excitement when he managed to gather a group of senior leaders for a meeting where they could learn about the issues we need to face if we are to tend and keep the earth God has entrusted to us (Gen. 2:15).

Sam was one of the founders of the John Ray Initiative, an organization that aims to help people understand the Christian imperative to care for creation, and he was heavily involved in the Christian conservation charity A Rocha. It is hard to defend the intrinsic value of an ecosystem without some sort of faith or philosophical commitment, and Sam taught that “to a Christian, nature is valuable because it is God’s—created by him and declared to be good.” He believed very strongly that caring for creation is just as much a Christian act as meeting together as a church on a Sunday.

Toward the end of his career in science, Sam won the UK Templeton Award for “long and distinguished advocacy of the Christian faith among scientists.” The student who gave a tribute at his service of thanksgiving was just one of the many people who are very glad that Sam had not been ordained or become a teacher or an overseas missionary. When I was a graduate student, I also appreciated his example: Sam showed us that it is indeed possible to be a real scientist and have a real Christian faith.

Dr Ruth M. Bancewicz is a Senior Research Associate at The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion in Cambridge, UK. Her PhD is in Genetics, and she has worked at Edinburgh University as well as the UK-based professional group Christians in Science. Ruth blogs at www.scienceandbelief.org.