It’s the Internet at its worst.

It’s the Facebook commenter who blames the president for everything from crime statistics to bad TV, the sort of thing I see daily in my work as social media editor at the Chicago Sun-Times. It’s the comments on a recipe for "Amazing Rainbow Tie-Dye Number Surprise Cake" posted on a radio station website that veer away from baking into personal attacks and politics.

Writer or reader, Christian or secular, conservative or progressive, nearly anyone who spends any significant time online and on social media has encountered it: trolling. This is the universal experience of the Internet.

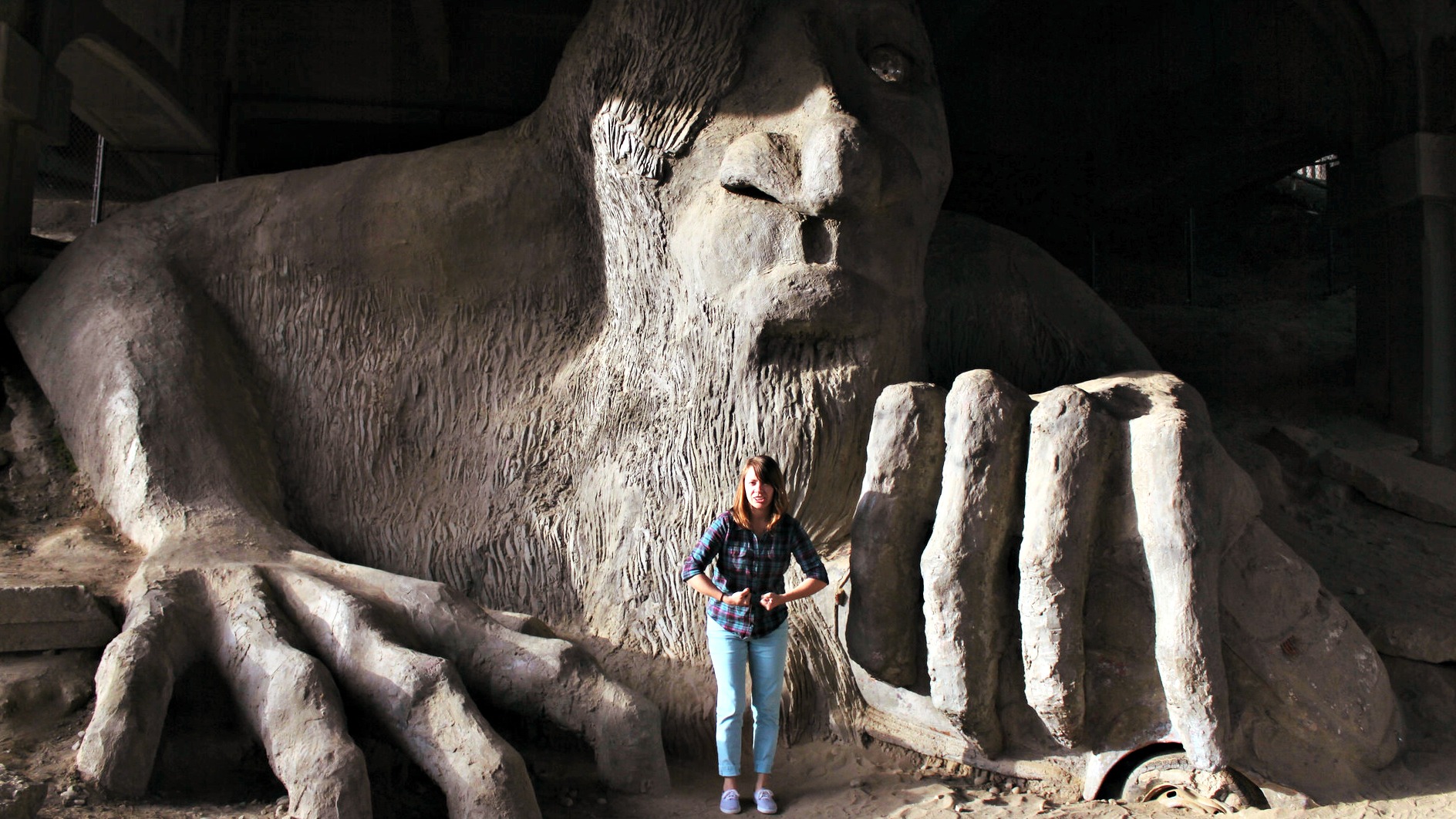

Trolls rear their ugly heads to remind us about their conspiracy theories, personal issues, political grandstanding and, of course, how our misguided theology has us bound for hell.

And they’re everywhere, from mainstream news websites like the Sun-Times to right here at CT. Both recently removed comments from most articles; the Sun-Times, temporarily while working on a new system to “encourage increased quality of the commentary;” CT, saying, “our efforts to carefully and thoughtfully report on controversial subjects have been swamped by comments that do not reflect the mutual respect and civil conversation we want to promote.”

“I guess most everybody feels like they’ve been trolled,” said Micky Jones, a seminarian at George Fox Evangelical Seminary and the North American Institute for Indigenous Theological Studies. “There’s a fine line between Twitter activism and going after somebody and engaging. It’s one of those things people get really self-righteous about.”

Trolling is an intentional disruption of online communities. That’s the classic definition, around since the late 1980s, used by The New York Times in its 2008 article “The Trolls Among Us.” It’s done to “make people angry or otherwise disturb them,” one self-described troll told me on Twitter, adding he often targets people “who needs [sic] to see how ridiculous they’re being.”

Trolling is not disagreeing. Disagreement is part of any healthy conversation — social media and website comments at their best.

Trolling, on the other hand, ranges from online raging to harassment. The New York Times article recounts the 2006 suicide of Mitchell Henderson, a seventh-grader from Rochester, Minnesota. Afterward, trolls, who inexplicably found the whole thing funny, hacked Mitchell’s MySpace account and harassed his grieving parents with prank phone calls.

Earlier this year, Jamie Nesbitt Golden explained on xoJane what happened when she, a black woman, switched out her Twitter avatar for a “white, bearded hipster guy”; she noted “a drop in random trolling, and a difference in engagement.” Pacific Standard and The Atlantic opened a discussion on the misogynistic online harassment faced by female journalists.

And on Monday, the female editors of Jezebel published a post describing their struggle with a troll posting pornographic images in the comments on the blog. It's upsetting to readers, they said, "and especially to the staff, who are the only ones capable of removing the comments and are thus, by default, now required to view and interact with violent pornography and gore as part of our jobs.”

So how are we, as Christians, to respond to trolling?

Thou shalt not feed the trolls

The first commandment of the Internet is this: “Don’t feed the trolls.”

The reasoning is simple. If the intent is to make people angry or otherwise disturb them, the way to shut it down is simply not to respond. And certainly, there are Proverbs that speak to the futility of answering – or not answering – a fool.

Most of us could be better about this; all have fallen short and returned snark for snark. And people are watching, according to progressive Christian writer Emily Timbol; commenters on one of her own posts took her to task after she left a snide comment in response to a troll’s comment on another writer’s post on the same website.

Still, there also are times when responding can be the most Christ-like thing to do. There are times when a response can assure other would-be commenters it’s not all trolls on the Internet. There are times it can further the conversation. And there are times a gentle answer can turn away wrath.

“There are real people behind this account. There are real people and real emotions,” Timbol said.

Thou shalt not troll

After the rainbow cake meltdown, Christ and Pop Culture gave voice to our collective frustration with trolls, asking, “Who ARE these people? Seriously.” In his post, writer Luke T. Harrington said:

I realize that I’ve probably been one of them myself. Not every day; maybe not even every year. But there have been moments—when I was tired and needed to blow off some steam; when I had had a bit too much to drink; when I thought “defending the Gospel” was the same thing as calling people stupid—that I’ve engaged in some pathetic trolling as well. Don’t try to pretend you haven’t either. On some obscure message board under a pseudonym, maybe? Maybe with somebody’s racist aunt on Facebook?

Our response to trolling, Harrington suggests, begins with our own online behavior – removing the digital plank from our eyes, so to speak.

For Jones, deciding how to respond to Internet postings begins with checking herself, asking if this is somebody with whom she normally would engage. Sometimes the seminarian tries to take the interaction offline, a tactic she learned about a year and a half ago when she was shown the same grace.

She’d gotten into a back-and-forth online with another podcaster, and he invited her to have the conversation face-to-face (as best as possible) on Skype. It quickly humanized the conversation and changed the entire tone, she said. It also weeds who is trolling from who is “gently, humbling wanting to engage to exchange ideas and learn from another person.”

Love thy trolls

But even when a person is trolling, Jones said, “they’re still a human being. They’re still a person Jesus is crazy about. … It sounds cheesy, but it really does boil down to loving that person – am I being kind to that person? And it can be real hard to do on the Internet.”

It’s the Golden rule: Treating others on the Internet the way you would want them to treat you, even on your snarkiest, most impulsive of days.

It’s loving your neighbor. It’s loving your enemy. It’s returning kindness to those who are unkind; after all, as Jesus said, anybody can love those who love them.

And, when it becomes too much, it’s knowing when to log off.

Emily McFarlan Miller is an award-winning journalist and truth-seeker based in Chicago. Connect with her at emmillerwrites.com.