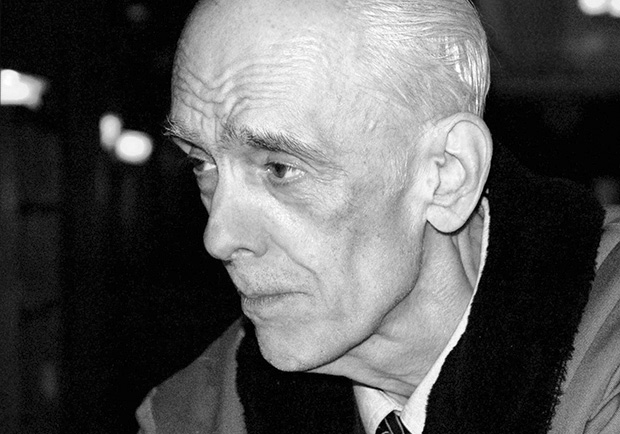

John McCandlish Phillips' eyes rolled open as I stood silently by his bedside with my wife Darilyn Saturday night. He raised his brow upward in greeting. His eyes cleared and his left hand moved up in a weak wave.

The legendary reporter for the New York Times was laid low by failing lungs, but he ministered to the very end. He encouraged, mentored, and prayed. John was a genius in giving deft encouragement to everyone who visited him with those wrinkles on his forehead rising and eyes growing large with warmth and encouragement.

A few days earlier he was still able write, though unable to speak through the breathing apparatus (he laughed with pleasure when I called it his astronaut mask). In wobbly block letters he would write bedside orders for the visitor to continue their calling in the Lord. His friends collected a whole book of these "marching orders of the Lord via John." You always felt that it was such a privilege, such a joy, and such an encouragement.

Weaving his writing up and down the page, he wrote a large bedside order to me. "Your Story, the photographer Jacob Riis, must be fully told." Riis was the outstanding Christian reporter in his day 100 years ago, just as Phillips was in his. In 2007, Phillips won the Jacob Riis award for lifetime achievement in journalism from the Christian journalist group Gegrapha. The group thanked Phillips for "exemplifying the values, integrity and journalistic excellence practiced by New York reporter and photojournalist Jacob Riis."

Phillips was born in Glen Cove, New York, on Long Island on December 4, 1927. He was known as Johnny, though later he warned people that he didn't like to be called that. Directly from high school, he started work as a reporter. While in the army, he attended a church service at which he was born again.

After getting out of the Army, Phillips worked for the Times from 1952 to 1973, mostly as a reporter in the Metro section. He kept a big Bible on his desk, which he frequently consulted. He also had a way of praying stories into being.

One time Phillips was stumped on how to do a breaking news story from his desk on a train derailment in New Jersey. He didn't have much time; I believe it was something like 40 minutes before he had to file the story. He walked to the water cooler, all the while praying. He took a drink, and walked back praying. At his desk he realized that he could try to call businesses that were situated along the area of the railway crash. He quickly found a businessman who said he saw the whole crash from his store. "God answers prayer! He sure does!" John told me. He scooped everyone with his story and its eyewitness account.

His most famous story was a front page profile in 1965 of the New York leader of the Klu Klux Klan. Headlined "State Klan Leader Hides Secret of Jewish Origins," the story was a terrifically reported profile of Daniel Burros, a 28-year-old Queens man who was the Grand Dragon. The reporting was dangerous and the Times offered to assign bodyguards to Phillips, an offer that he waved away before the article was printed. Phillips went personally to Burros to confront him with the story and in effect to give him a chance to repent. Burros didn't change his views but later committed suicide. After publication, the Times insisted on security for Phillips.

He also wrote the About New York column. He wrote of missionaries coming home, ne'er do wells in Times Square, and a dramatic skit about monks and their bells. Phillips described the action on stage: "The time has come to ring the bells, And, O, how those bells are pealed that morning! Around and around the monks go in widening circles, running, skipping, leaping, twining their ropes together! Into the air they go, denying their last inhibition, greeting the new, the hilarious morning!"

Phillips was like that: He had an uninhibited love of the Lord that he mixed with his love of journalism. As a result, he encouraged so many Christians to go into journalism.

There were not many Christians going into journalism in the 1970s and 1980s. Phillips talked about his own experience, "I keenly remember a time when it took about four years of prayer, reaching out, of writing articles and speaking at Christian colleges, and encouraging and mentoring to see one young believer enter the news media."

When Russell Pulliam of the Indianapolis News was working for the Associated Press and living here in New York, Phillips was his cheerleader. He encouraged Pulliam to think christianly in the way he did his reporting. He promoted the career of The New York Times reporter David Gonzalez, particularly endorsing Gonzales' wonderful series about a West Harlem Pentecostal church "House Afire."

Phillips was a great encourager. When David Cho of The Washington Post was wondering if there was a future in journalism, Phillips told him that he needed to stay as an example to other Christians.

At the New Testament Missionary Fellowship, which Phillips helped to found, there were always journalists going in and out. Phillips helped Jaan Vaino, who worked for CBS News for twenty-four years, to escape a particularly bitter spiritual darkness.

Early in her career as a producer for NBC, Alice Rhee had to cover the 1996 crash of TWA 800, the third deadliest commercial passenger jet crash in American history. She remembered the event at a meeting honoring Phillips, "During the press conference, the family members wept and wept. I could barely speak. And I cried until my blouse was damp." She told Phillips that she didn't know whether she could make it as a reporter. She recalled his response, "How can you move your reader, your audience, unless the story has first moved through you?" Now recognized as one of the best television news producers, she continues to do emotionally sensitive reporting. She regularly visited her mentor in the hospital.

From his bed in the intensive care unit Phillips was a powerful mentor. He wrote to my wife, a designer of coffee table art books: "Speaking of God's gifts, he has given an amazing one to Mrs. Carnes!" Periodically, he would ask her to get some books from her publishing company so that he could give them as gifts. He wanted to invest encouragement into her calling.

Imagine. Phillips was the guy flat on his back, unable to speak except some sounds here and there, struggling to raise his arms, and yet still sharp as a tack mentoring, encouraging and praying with people!

To encourage the dozens and dozens of people who came to visit him, he developed a whole ensemble of gestures, grunts, eye shifts, wrinkled brows, waves, thumbs up (single, double, waved up, held up high and steady, slow, slight, resting on his chest, pointing outward, pointing inward, pointing upward with eyes raised), and hands raised palm up and out to mean "of course," raised in praise, and clasped in an intense prayer position. You could feel his smile through his eyes which would shutter down in tiredness after a while but would zoom open with a bright light when you started to pray.

His friends knew that he prayed for them several hours a day in his tiny, claustrophobic apartment across from Columbia University. On his bed in St. Luke's Hospital he prayed as if on the royal road to heaven with such concentration that you knew he was ready to see the Lord.

On the last evening that we saw Phillips, he used every ounce of his strength to acknowledge us. His left arm was stronger so he slightly lifted it while we held his right hand. He had big hands, and his grip was still very strong. When my wife Darilyn said he was a faithful servant in prayer to the Lord, his eyes lit up for the last time for us. It was like a cinematic glimpse of Heaven. He was ready to pray for an eternity.

Tony Carnes is a senior writer for Christianity Today and founding editor of Journey Through NYC Religion.