It began with crisis, and it ended in worship.

The Third Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization, held October 17-25 in Cape Town, South Africa, was the first gathering of evangelical Christians to attempt to accurately represent the reality of today's church leadership. Though the West had a strong voice, its numbers were much smaller than the enthusiastic, unintimidated participants from Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Consequently, the congress had an atmosphere of continual discovery, as participants looked around and saw the teeming diversity of global faith. Ugandan Anglican Archbishop Henry Orombi told a news conference, "It is a joy to see heaven begin here."

The Lausanne Movement used a highly decentralized process to select participants. A committee in each country chose delegates in numbers proportional to its nation's evangelical population, based on Operation World statistics. Out of a total of 4,000 delegates, the United States got to send 400, Canada 50, the UK 80, and China 230. Selection committees were to include the full spectrum of churches and ethnicities, to assure that at least 60 percent of their choices were under 50 years old, 10 percent under 30, and 10 percent from the "marketplace." Women were to compose at least 35 percent.

A point of contrast: At the Edinburgh World Missionary Conference exactly a century ago, there were 1,200 delegates: 500 from the U.S., 500 from Britain, 4 from Asia, and none from Africa. The world has changed, and Cape Town 2010 embodied the transformation.

The China Crisis

China's emergence as a robust participant in world evangelization is an astounding part of that transformation. Chinese took up Cape Town with enthusiasm, choosing their allotment of 230 participants and raising money not only to pay their way but also to enable Christians from neighboring countries to come. (The top four national groups providing financial support to the congress were the U.S., China, South Korea, and India.)

But as participants began to arrive in Cape Town, news came that Chinese authorities were stopping delegates at the airport. Only a handful made it to Cape Town, leaving a gaping hole in the second night's program, which was set aside to celebrate God's work in Asia. "It's like having the World Cup and not having Brazil," said Doug Birdsall, Lausanne's executive chair.

Then came the shocking news that the conference's website and links to 600 GlobaLink sites in 92 countries had been attacked and shut down by sophisticated hackers. In addition, a virus infected on-site computers and slowed computer operations and Internet access to a crawl. It took two days for officials to fully understand the situation. Providentially, two cousins from Bangalore, India, had come to do volunteer IT grunt work. They offered their expertise and were able to set up systems to defend against the attacks.

China was strongly suspected of being behind the attacks. But certainty is impossible, and Lausanne staff have been careful not to point fingers. They do not want to make life more difficult for Christians in China or create lasting antagonism toward the Lausanne Movement. "We want to be peacemakers," Birdsall said. "They may not understand the unstructured nature of evangelicalism, let alone the Lausanne Movement. It's hard for a highly structured society to comprehend that we do not have any strategy for any country in the world."

Philemon Choi, an influential Hong Kong leader, told me that delegate selection had been mishandled. "They chose all 230 delegates from the house church and then invited the [officially recognized] Three-Self Church. That's not how you do it. To repair the damage, we must meet face-to-face." Lausanne leaders hope to visit China soon.

Despite these crises, Cape Town 2010's complex operations came off superbly. Occupying a gleaming convention center near Cape Town's beautiful waterfront, the tightly scheduled, fast-paced conference fully integrated drama, dance, video, and art. "The triumph of the conference," said Calcutta Assemblies of God pastor Ivan Satyavrata, "was how it engaged all the senses."

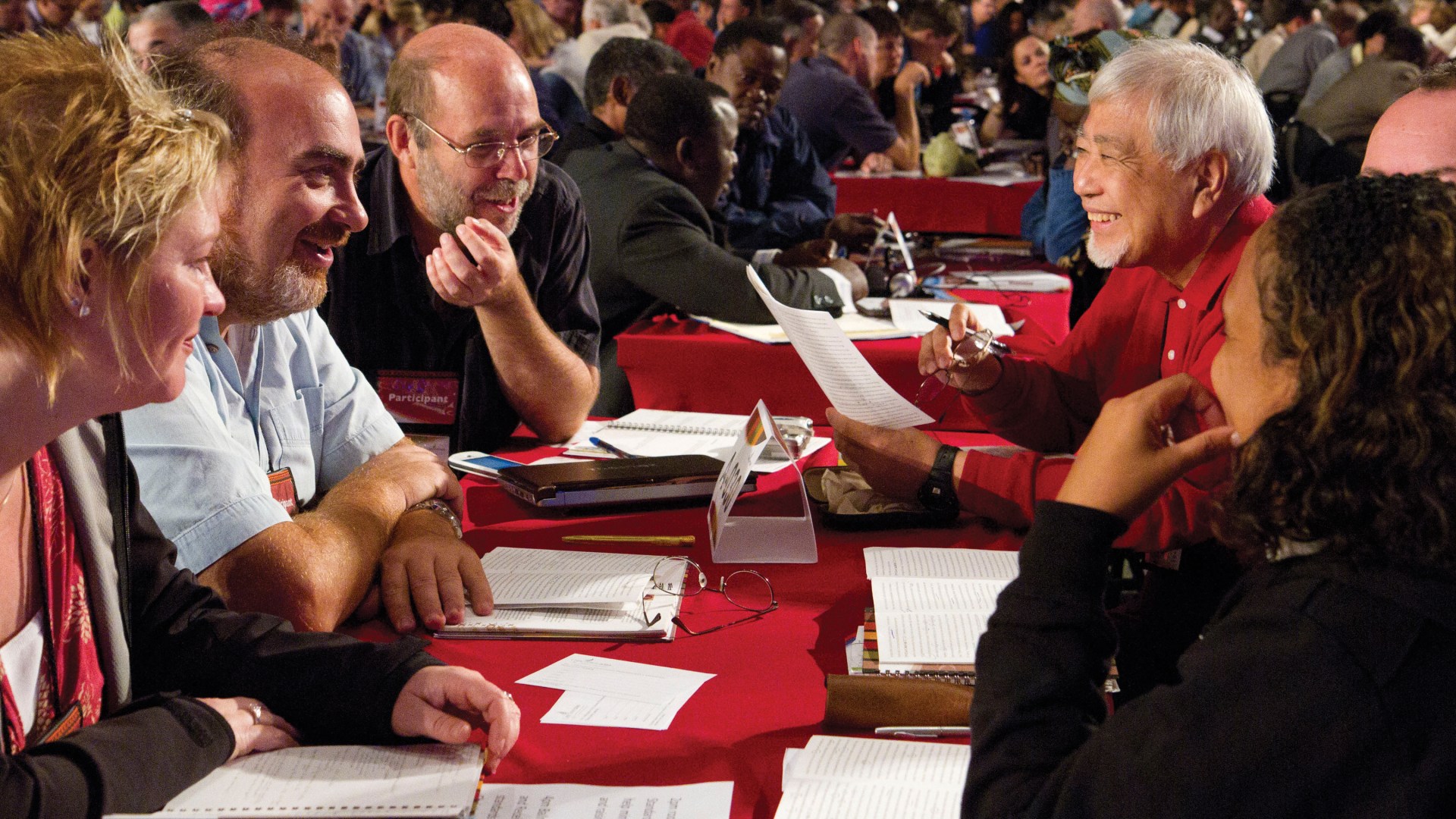

For many, the table groups were the most significant innovation. The main hall was an almost endless carpet of tables for six. Each participant was assigned a group for the week, carefully managed for diversity. One hundred and fifty table groups were set by languages other than English so that participants could talk freely. Global diversity was an experiential reality as table groups responded to Scripture together and shared their reactions to key issues. Many participants told me that table groups were the innovation they appreciated most; they only wished they had been given more time to converse.

The high-tech program kept speakers on a tight leash, provided a hailstorm of facts and perspectives, and sometimes overwhelmed participants with information they had little time to reflect on. Never boring, it had the downside of not allowing time and space for some non-Western cultures to be themselves. All congress presentations were in English, the one language shared by all who were providing simultaneous translation into seven other languages. But some Latin American and African speakers struggled to read English scripts. Running translation would have taken twice as long for the same content, but would have let in more humanity.

I asked Femi Adeleye, a Ghanaian plenary speaker, if the planning process had been representative of the global participation. "'No' would be my honest answer," he said. "Planning has been mostly Western. They sent us the plan, but the template was already established. We could only influence the margins."

Ruth Padilla DeBorst, a Latin American who gave one of the morning Bible expositions, felt similarly. "This was their program, and we attended. It should be ours, if this is the global church. Technology became the driving force."

Nevertheless, speakers from five continents gave wonderful daily expositions of Ephesians. Others shared amazing testimonies. Eighteen-year-old Sung Kyung Ju told of her determination to witness for Christ in her native North Korea, even though her father, a former high-ranking official, evidently gave his life doing the same. Libby Little read notes for a devotional talk from the bloodstained notebook of her husband, Tom, who was murdered August 5 alongside nine other aid workers in Afghanistan.

Naturally there were grumblings. While John Piper was a favorite expositor for many, others resented his importing controversy over eternal suffering into an Ephesians text that had nothing to do with it. Some regretted that N. T. Wright was not invited to speak, sensing an underlying attempt to steer the evangelical movement toward a particular kind of theology. Arnold Van Heusden, until recently head of the Evangelical Alliance in the Netherlands, thought he detected a defensive note in the program.

Others saw just the opposite. Cape Town 2010 included several strong pleas for women's equal participation in ministry, and featuring Padilla DeBorst as a Bible expositor was a seminal event. Strikingly, evangelicalism's past debates over evangelism taking priority over service seemed finished. Speaker after speaker emphasized how integrally the two are related in witness.

Cape Town 2010 provided no theological or missiological breakthroughs. It did, however, provide something Lausanne international director Lindsay Brown hoped for: a ringing affirmation of the uniqueness of Christ, the authority of the Bible, and the imperative of world evangelization. "I think there's been slippage," he told me as the conference began. But slippage was hard to detect in participants' enthusiasm for traditional evangelical affirmations.

The Cape Town Commitment

"We didn't want a jamboree of evangelical triumphalism," said Christopher Wright, international director for Langham Partnership/John Stott Ministries. In a stirring address, Wright compared in detail the state of the church today and the church in the generations before Luther. "What is the greatest obstacle to God's mission in the world?" Wright asked. "It is not other religions or a resistant culture. Our idolatry is the single biggest obstacle to world mission. We are a scandal, a stumbling block to the mission of God. Reformation is the desperate need of our day, and it must start with us. If we want to change the world, we must first change our world." He called for a new reformation beginning within evangelicalism.

Participants devoted much of Saturday to repentance and prayer as they responded to Wright's call to reflect on the movement's lack of humility, integrity, and simplicity.

That same day, Lausanne leadership released part one of the Cape Town Commitment, a statement of belief written by a committee headed by Wright. The committee will complete the second part in the weeks after the congress, and aims to express commitment to action.

Part one is long—16 pages of theology—but beautifully expressive at many points. Notably, the commitment is framed as a covenant of love: God's love for us, and our consequent love for him and for the world. "Near the beginning of drafting," Wright told me, "I asked John Stott what he thought of that approach. He approved. 'Evangelicals usually write statements that affirm or deny, but this is the language of love.' "

Fittingly, the commitment's framework became part of Cape Town 2010's final communion service, so that participants "owned" it through worship rather than a signing ceremony.

In the most famous line from the 1910 Edinburgh Conference, Indian Bishop V. S. Azariah thanked Western missionaries for all that they had brought but asked for one more thing: "Give us friends," he said.

Cape Town 2010 suggested that Azariah's plea has been answered. Both in Lausanne's diverse leadership and in the congress's everyday mingling, it was hard to overlook the genuine love and personal appreciation. Partnership is a step further, and the congress suggested we are only partway there. The diverse sides are still learning how to plan and work together. Cape Town 2010 provided part of the learning process.

"We have a global mission," said Satyavrata, "and I think it's important to have one moment in 20 years for people to come together in one room and see what each other look and talk like."

"Evangelicalism has exploded," Birdsall told me. "But it has also fragmented. We needed something to bring us together."

Tim Stafford is a senior writer for Christianity Today.

To read the Cape Town Commitment, go to Conversation.Lausanne.org/en/conversations/detail/11544.

Copyright © 2010 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

See CT's special section on Cape Town 2010, as well as the year-long pre-Congress Global Conversation hosted by CT and the Lausanne Movement.

Previous articles on Cape Town 2010 include:

Underrepresented at Cape Town | Meditations on missing megapastors. (October 22, 2010)

Who Got Invited to Cape Town and Why | Cape Town 2010 claims to represent the global evangelical church. How did they do it? (October 20, 2010)

This Time For Africa | Continent-wide runup to Capetown 2010 draws more than 58,000 to Christ. (October 18, 2010)

China Blocks Delegates to Lausanne | Lausanne delegates from China were turned back at the airport. (October 15, 2010)

The Most Diverse Gathering Ever | Lausanne III is pulling a cross-section of 4,000 world leaders to keep the gospel front and center. (September 29, 2010)