Take a Friday night walk through Havana's Parque G to see up close how much Cuba needs Christ. By day, the downtown park offers a pleasant stroll along a wide, tree-lined boulevard down to the gulf coastline. By night, Parque G becomes a murky zone where Cuban teens, dressed somewhere between hipsters and goths, cluster to smoke, drink, and exchange drugs. Young couples hide in the shadows of bushes as musicians hold jam sessions under streetlamps.

But in dramatic contrast to the surrounding activity, at 1 a.m. 25 young Cuban Christians form a circle to pray. Holding hands, they shout forceful prayers toward heaven for the salvation of Cuba. Across the intersection, a uniformed police squad watches with interest, but does nothing to stop their outreach.

The youth belong to Alcance Victoria, an evangelical Cuban church formed in 2003 based on the inner-city models of evangelist Nicky Cruz and Victory Outreach, an international ministry. Most of the youth are new believers and recovering drug addicts thanks to the church's weekly evangelism walks.

"Too many churches live their faith inside their walls, when the church needs to be here in the street," says dreadlocked evangelist Obeda, a former street kid whose brilliant white grin contrasts with his ebony skin. "We're out stealing souls from the Devil."

Speaking enthusiastically with visiting Christians, the teens point to each other along the organic human chain of who brought who to faith in Christ. Their style is direct—"Hi, I'm a Christian, and I'd like to tell you about Jesus"—and brings results. The church is 500 strong, and leaders hope to add another 500 by year's end.

Their leader, Manuelito, shows no fear of arrest. He says Havana police need their help in confronting the recent wave of street drug abuse. "If I wasn't afraid when I was doing drugs in this very park," he says, "why would I be afraid now that I have the truth?"

The edgy street evangelism in Cuba's capital reveals that Western perceptions about Cuban Christianity seem woefully outdated.

"Here in Cuba the church is alive, growing, faithful, and active, persevering through difficulty," asserts a prominent evangelical leader. "We are working inside Cuba now, and someday we will join everyone else in the missionary activity of the world."

Since the 1959 Revolution, Castro's Communist government has placed numerous restrictions on religious expression in Cuba—a reality illustrated by most sources' requests for anonymity (see "More Freedom But Not Free," page 28). Yet the Cuban church is thriving despite its limitations, and its leaders ask that their church not be used as a geopolitical pawn. "We are part of the body of Christ in the world, yet people see us only with political eyes," said one leading Cuban evangelical. "To those people we say: 'Come and see.' "

Christianity Today traveled throughout the island from Palm Sunday to Easter Sunday. The journalistic Holy Week pilgrimage revealed a surprisingly healthy church with a new generation of young pastors boldly pushing old boundaries. Their current evangelistic zeal is best summed up in the recent modification of a common evangelical rallying cry: from "Cuba para Cristo" to "Cuba para Cristo—ahora." Cuba for Christ—now.

Joy In His Presence

Since the 1990s, major changes have buffeted Cuba's 11.4 million people. After the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union, Cuba's heavily subsidized economy collapsed, causing Cuba's "Special Period" of economic crisis, famine, and more than a decade of hardship.

In 1992, the ruling Communist Party changed the state constitution to refer to Cuba no longer as "atheist" but only "secularist." In 1998, the late Pope John Paul II visited Cuba, raising expectations of new religious tolerance.

Cuban evangelicals told CT that the economic depression and concurrent revival has fed the spiritual hunger of many Cubans, largely nominally Roman Catholic. Dramatically higher attendance at established worship services and explosive growth of new casas cultos ("house churches") are two impossible-to-ignore signs of the vibrancy of Cuban Christianity today. The Assemblies of God, Cuba's largest Protestant group at 3,000 churches (up from 90 in the previous decade), for years tracked new congregations on a large wall map at their headquarters. But when growth exploded, they stopped adding red dots because it became impossible to display all the new churches on a single map.

The Eastern Baptists, Cuba's second-largest Protestant denomination and historically linked to the American Baptists, have grown from 6,000 adult members in 120 congregations in the 1990s to 27,800 adult members in 1,200 congregations. Its 3,100 baptisms in 2008 were the highest number in the denomination's 100-year history. Methodists, Western Baptists, and Los Pinos Nuevos, a leading indigenous denomination, have also enjoyed significant growth.

Cuban Protestants represent 4 to 6 percent of the island's population (between 450,000 and 700,000 people). Growth has been most robust in urban areas among denominations actively planting casas cultos, legalized in the 1990s in response to a surge in attendance at established houses of worship.

For Palm Sunday, CT traveled to a Havana suburb for worship at a casa culto. The new believers, mostly elderly women, squeezed themselves into the living room of a narrow cement house. This suburb has many followers of Santeria, a syncretistic Afro-Caribbean religion that at one time included this home's owner, who was a priest-in-training. In the entryway of the home is a stripped altar, now adorned with a simple pot of purple flowers. (Home altars are central to Santeria practice.) The owner came to Christian faith after witnessing his wife's baptism.

The group is only 13 strong, but its members' voices resound off the pale blue walls as they sing "Somos el Pueblo de Dios" ("We are the people of God") from manila folders. They close in prayer, mostly for estranged family members. Ending the service, they read aloud promises of God, many from the Book of Isaiah, out of a small wooden box of cards.

The mid-30s pastor emphasizes empowerment. "This is your job, to go and talk to your neighbors and bring them to church until all Cuba is for Christ," he says. "Remember: The vision of our group is to multiply and divide. Right now we are small, but we will multiply."

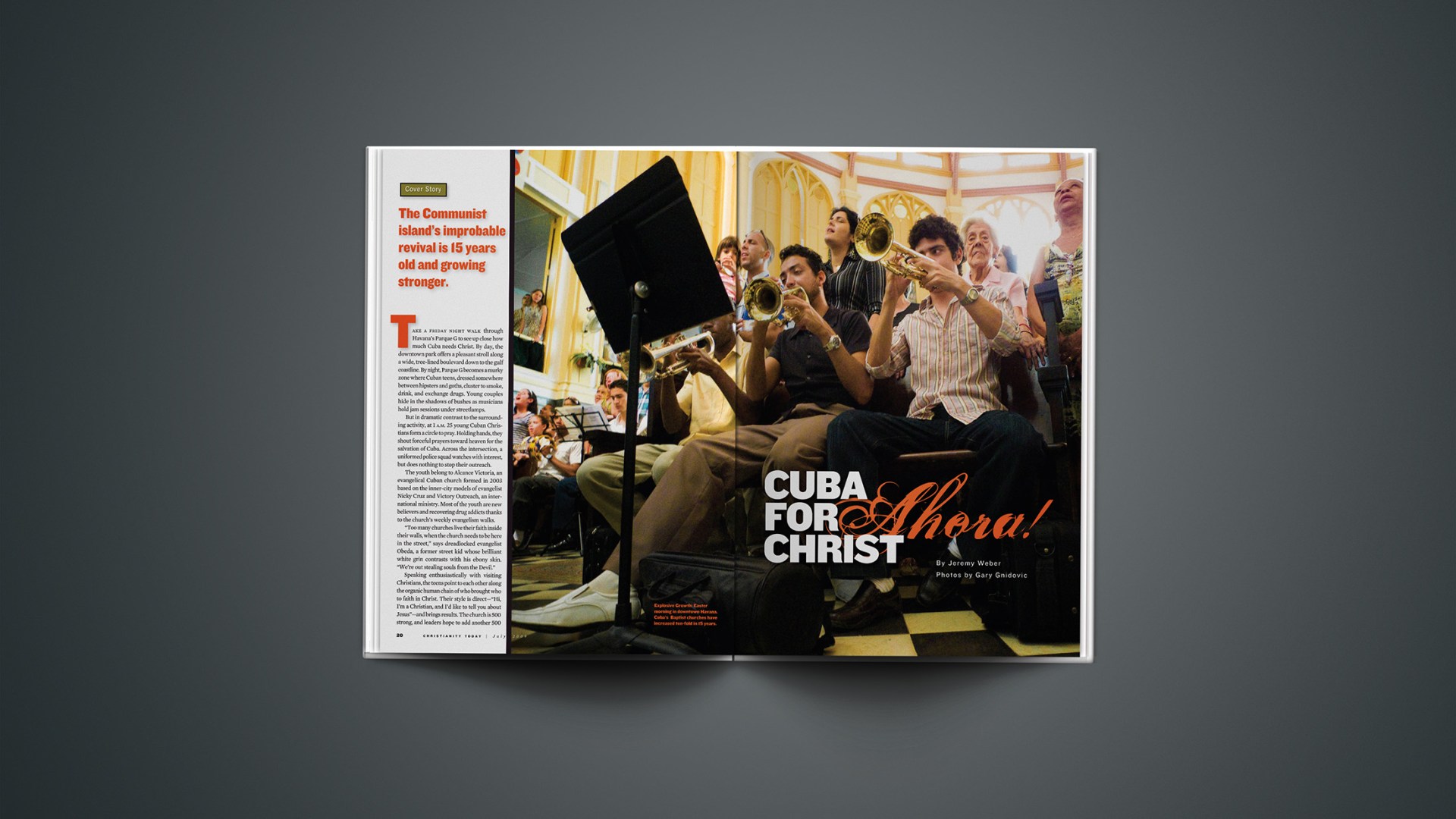

Later on Palm Sunday and across town, the afternoon service of Alcance Victoria offers an arresting example of this kind of believer multiplication. In the hours before and after the service, a multiracial mix of youth arrives in waves as public buses pass by, and eventually 250 pack out the pink sanctuary. The towering charismatic pastor frequently towels off his head as he preaches on the "si se puede" ("yes, it can be done") power of the gospel to change lives.

The crowd bursts into enthusiastic handclapping for the salsa-flavored worship song "Gozo en Tu Presencia" ("Joy in Your Presence"), and jumps in unison to a resounding Cuban rendition of "I'm Trading My Sorrows." Obeda and Manuelito, with fists pumping in the air and faces bursting in smiles, have clearly done just that.

Academics may point to the Special Period and televised state celebrations of Protestants in 1999 as giving first impetus, then tacit permission, to the largely atheist populace to convert to Christianity, but evangelical leaders disagree. "The revival in the church can solely be attributed to the movement of the Spirit of God and the witness of the Cuban church," said a leading Cuban evangelical.

Other factors include hundreds of pastors receiving specialized training in evangelism and church planting in recent years. House churches offer a more accessible environment than formal sanctuaries. And after Cuba's devastating hurricanes in 2008, local churches repaired the roofs of their non-Christian neighbors first before repairing the roofs of church members. This won evangelicals new respect.

"It's important that the gospel be lived out," said a leading Cuban evangelical. "This is what makes people notice that there is something different about Christians."

More Harvest Than Workers

Driving east from Havana into the heartland, the sun lingers on the horizon of Cuba's solitary highway, highlighting sugar cane, banana, and tobacco crops. How does one drive at night on a six-lane autopista with no lane markings and nearly as many bicycles and cows as cars?

"Por fe," replies a local pastor. By faith.

The highway passes through central cities where seminaries have established extension campuses to cope with record enrollments spurred by burgeoning churches' needs. Most seminaries have opened their doors to pastors from outside their own denomination, and now offer niche training in youth ministry, worship, and missions. "The church is still growing faster than we can produce leaders," said a seminary leader. "But we are closer to keeping pace."

The Western Baptists, historically linked to the Southern Baptist Convention, have a record 94 students at their hilltop seminary in Havana, and almost 400 more at seven satellite locations opened in the past three years. The Nazarenes send distance-learning modules to 200 students from Pinar del Rio in the far west to Guantanamo in the far east. Last year's graduation of 73 students was the largest in the denomination's 100-year history.

Extension campuses alleviate space constraints at main seminary campuses and reach students who can't afford to relocate or attend full-time. Local pastors volunteer to assist the students in their region.

In one central city, CT stopped off to interview Mario, a 33-year-old pastor who on Tuesdays leaves his wife and two daughters and hitchhikes the 35 kilometers from his rural Western Baptist church of 70 to a Bible institute to teach New Testament. The trip can take three hours each way. "It's a miracle that I arrive," said Mario. "It's a sacrifice to leave my flock alone, but it's worth the pain. We must train new pastors well."

Tourists driving through Cuban cities may be struck by the number of local residents who seem to spend their days idling on porches. But the average Cuban pastor works 12-hour days, kept busy by weddings, funerals, and pastoral visits. "We have two kinds of pastors: those who are burnt out and those who are burning out," said an Eastern Baptist leader whose denomination has 202 ordained pastors for 390 congregations. "But it's a good problem when too many people want Bibles and too many places want preaching."

Capitol Contrasts: Above: Government, commerce, and poverty intersect in Havana. Right: Palm Sunday worship at Alcance Victoria. Below: Santeria shrines are common in Cuban shops.

Such rapid church growth has forced Cuban pastors to abandon traditional leadership models and delegate responsibilities to newly active lay leaders. "The church is growing because pastors have loosened power," said a 34-year-old pastor in central Cuba. Pastors in his rural network of nine house churches are allowing lay missionaries to plant churches and even conduct baptisms and weddings because the pastors can't travel enough to keep up with demand.

Cuban seminary leaders regard the pastor shortage as a challenge, but also as divine confirmation of their work. "A shortage of pastors is what the Lord tells us will happen," said a seminary leader, citing Matthew 9:37. "The problem would be if there was an abundance of workers and no harvest. Hopefully there will always be a lack of pastors—it means God's work is marching on."

Taking Risks, Making Mistakes

On a tranquil weekday evening during Holy Week, the cinema in a central town features a Cuban film of mystery vignettes. A short 10 blocks away, an evangelical church is hosting a film night of its own. About 25 people spread out on the worn wooden pews in the lime-green sanctuary as the 37-year-old lay leader delivers an evangelistic message before screening Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ.

Between the two screenings, the streets echo with salsa music, motorcycles, and a pastor's booming voice as a Western Baptist church concludes a special evening service to prepare for its first-ever outdoor Good Friday service and Easter Sunday street distribution of 35,000 hand-stamped tracts.

These efforts exemplify the new generation of evangelical leaders who deeply respect their predecessors who guarded the faith through tougher decades, but who have a new agenda.

"The church before was asking, 'How do we survive?' " said an evangelical leader in Pinar del Rio. "Now the church is asking, 'How do we multiply?' "

Today evangelicals are taking full advantage of their rights and probing the boundaries of the fuzzy gray area the government has given them for evangelism. In the words of one leading evangelical, "It's better to ask forgiveness than permission."

Cuban evangelicals say they are allowed to evangelize in public but not proselytize. This comes down to—as in many countries—a matter of interpretation, seemingly based on magnitude. Thus, evangelicals cannot use a stadium or TV program for an outreach event, but can pass out free evangelistic tracts or DVDs in the streets.

From west to east, Cuban evangelicals are testing new methods of outreach. A network of house churches in western Pinar del Rio sends young pastors on bicycles to new towns to find new believers and turn their homes into casas cultos. A Western Baptist church in Havana offers music and dance classes for local children. Alcance Victoria has launched Thursday evening prayer circles 100-strong on the Malecon, Havana's iconic seaside promenade.

Baptist churches in eastern Cuba, an area long resistant to evangelization due to widespread poverty and Santeria but today quickly becoming a Protestant center, are using an "Operation Andrew" approach: members write down on cards the names of 10 people, then pray for two months over the names before inviting those listed to a special service. Other churches host Sunday afternoon baseball games with gospel messages beforehand.

This effort to maximize the space between legality and toleration requires patience. After local authorities shut down a bold public screening of the Jesus film on the Malecon, a Western Baptist leader gave this advice to the evangelist organizer: "The Bible says we are to preach every day, so don't blow it all in one night, brother."

Today's younger generation of pastors take more risks as they advance the gospel. They also make more mistakes. "The old have experience, and the young have enthusiasm," said a leading Cuban evangelical. "You need both."

Global Training Ground

Traveling east, the palm trees get stouter as the land gets hillier. The highway narrows to two lanes with cactus fences on either side as farmers with straw hats, open shirts, and weathered faces travel by horseback across their fields.

This central area between Cienfuegos and Camaguey was for decades an evangelical no man's land far removed from denominations in major cities. Now missionaries come from all over Cuba to work in the numerous little villages that lack churches or sound preaching.

A popular-level view about Cuban Christians is that these believers live out their faith trapped inside an isolation box due to Communist Party control of information and travel. But the Cuban church has a robust view of its role as a cross-cultural, missionary-sending church. An intricate woodcarving on a seminary chapel wall captures this global perspective. The carving shows Cuba with arrows flying out from the island and planting a Christian cross on every continent—including Antarctica.

"The Great Commission is our responsibility as much as the church's in America," said an evangelical leader in central Cuba.

Pastors across denominations believe Cubans are well equipped to be missionaries. They know how to live on little, possess a well-honed apologetic theology, and would find greater welcome in nondemocratic or developing countries than Americans would. Given that many churches have a majority of members with advanced academic and professional degrees, the Cuban missions model would be a missionary who works by day as a doctor or engineer and plants churches at night.

This vision is in its infancy because both money to travel and government permission to go abroad remain hard to obtain. But Cuban Christians are also training foreign nationals to spread the gospel. Cuban universities have hundreds of foreign medical and engineering students. Some of these students come to Christ in Cuba.

After graduation, these students return to their home nations and spread the gospel. An Eastern Baptist pastor cites the example of a visiting medical student from Benin who became a Christian and has now planted seven churches while working at a Benin hospital. "They may not be Cuban," says the pastor. "But we are sending them to reach the world."

For now, Cuban missionaries are traveling to communities in the mountains of central Santa Clara and eastern Santiago. They are also removing the geographic boundaries that used to demarcate their denominations.

Island of Opportunity: One leader says, 'We have much more room to grow.' Above: Salsa in the Havana streets. Below: Lunch for two in Havana. Right: A sunrise Easter service.

For years the Western Baptists only worked east to the town of Santa Espiritu, and the Eastern Baptists only worked westward to Hativoco City. In 2000, they decided that "Cuba is one because Cuba is for Christ" and agreed to expand throughout the island. The Eastern Baptists are even changing their official name from "the Baptist Convention of Eastern Cuba" to "the Eastern Baptist Convention of Cuba," a subtle yet symbolic rebranding.

Denominational leaders say they have no concerns about competing with other church groups in a given city because the percentage of active Christians is so small. "What are two churches in a city of one million people?" said one leader. "We have plenty of space to work without bumping into each other."

On the Wednesday morning before Easter, CT watched as 22 Santiago pastors from nine denominations gathered in a pale peach chapel for their first interdenominational prayer breakfast. They encircled the room holding hands and sang as a small Yamaha keyboard played "En Cristo Somos Unos" ("In Christ We Are One").

"In the past our denominations were developing in cocoons," said an evangelical leader in central Cuba. "Today we have a shared vision of being the same body and are conscious of our common purpose: the abundant harvest at hand."

Evangelism Trumps Politics

At one highway checkpoint in the Cuban heartland, an evangelical leader received an unexpectedly positive reaction when the questioning officer discovered he was a pastor. The officer shared his appreciation for a group of pastors who delivered aid recently to the area heavily damaged by last fall's hurricanes.

After Cuba's devastating hurricanes in 2008, local churches repaired the destroyed roofs of their non-Christian neighbors first before repairing the roofs of church members. This won evangelicals new respect.

It was another indication of how public perception of Christians has changed. "They saw we remained steadfast to our faith through those hard years," said an Eastern Baptist leader. "Now we are seen as good people that contribute to society."

The history of the Cuban church after the 1959 Revolution can be told in three movements:

- The 1960s were a decade of persecution; the church declined in size as many Christians left Cuba or left the faith.

- The '70s and '80s were decades of discrimination; the church was consolidated to the faithful few.

- The '90s—when Cuba's Soviet support system fell apart—became a decade of revival that continues today.

Most of the pastors CT interviewed have had opportunities to leave Cuba, but said God has called them to stay and serve their native country. "The best place in the world for me is the center of God's will," said one 33-year-old Western Baptist pastor. "If you are there, you can withstand anything."

"All things have a divine purpose behind them," said a Pentecostal leader. "Our limitations have caused the church to grow."

For example, government restrictions on new church buildings have caused the Cuban church to multiply all the faster, expanding organically from house to house versus the years it would take—because of shortages of money and materials—to construct a bigger sanctuary. A prime case in point: In the lush valley leading down from the Sierra Maestra mountains to the eastern port city of Santiago, an Eastern Baptist nursing home—another new method of outreach—has been under construction for seven years with no end in sight.

"We would like to have permission to build templos [sanctuaries], but if having a templo would limit our vision for evangelism, we would rather not have them," said an Assemblies of God leader. "We would rather keep going out into the streets and reaching out to people than remain in the templo and wait for people to come to us."

Cuban evangelicals are quick to express gratitude to the American missionaries who brought them the gospel in the late 1800s. Many evangelicals said their greatest desire is not for more political and economic freedom, but for active faith. "Of course I want more freedom, but I wouldn't want it to come at the expense of our current passion for the gospel," said a leading Cuban evangelical.

"Perhaps God is limiting our freedom to teach us," said an Eastern Baptist leader. "To strengthen the church so that when more freedoms are granted to us, we will be better prepared to serve."

Harvest Time—After Decades of Prayer

During the dry season, the drive from eastern Cuba back to Havana winds through vast stretches of parched brown farmland and blackened fields, the only color being the bright purple flowers of the bougainvillea bushes that line the roadside. A former local pastor insists the land will burst into green in the post-Easter rains of coming months.

His statement seems an apt metaphor for the future of Cuban evangelicals. Back in Havana, at a drama and dance-filled Good Friday service, an Assemblies of God pastor explains how his church has doubled in size since launching public outreaches, including hospital visits and a puppet ministry. Today 200 will crowd into its small basement sanctuary on Sundays.

"We are changing our focus," says the mid-30s pastor. "People think our church is doing well because we are bursting out the doors. But compared to the neighborhood, we have much more room to grow."

Walking west along Havana's Malecon late Saturday night during Easter vigil hours, one passes eroding buildings and a virtually unbroken string of Cubans of all ages and ethnicities sitting on the seawall, overlooking the crashing waves as they fish, smoke, drink, or cuddle. Upon reaching the iconic National Hotel, the sound of salsa emanates not from the nearby nightclubs but from a circle of 34 Christian teens, all recent converts, exuberantly playing worship songs on two guitars, a bongo, and a tambourine.

When asked what denomination they represent, a 19-year-old Afro-Cuban girl demurs, saying, "We are all one in Jesus. Denominations aren't important." Further questioning reveals they are from the Assemblies of God church that hosts Alcance Victoria. The street evangelism model is spreading.

Hours later, at an Easter sunrise service in an ocean-side Havana suburb, 60 believers sit on white patio chairs on a third-floor rooftop and sing the Easter hymn standard "He Lives" as tropical birds sing and morning traffic thunders. The rising sun casts a strong orange light on the pastor's face and long shadows on the backs of his congregation. They pause and turn to watch through rusted chain links as the bright sun crests the wall of rooftops on the horizon.

On Easter Sunday, most evangelical denominations began campaigns of 50 days of prayer for the evangelization of all of Cuba. Their enthusiasm is palpable and infectious, and perhaps well founded given that this—a most improbable revival—has lasted 15 years and is still going strong. "This is God's time for Cuba," said a seminary professor. "Cuba for Christ. It's time to pick up the harvest."

"It is the movement of God," said an Eastern Baptist leader whose grandparents spent decades praying for such a revival. "And the greatest revival is yet to come. In the end, we want to see all of Cuba for Christ."

Jeremy Weber is CT's news editor. Download a companion Bible study for this article at ChristianBibleStudies.com.

Copyright © 2009 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Christianity Today July's cover package on Cuba includes "Audio Slideshow: Easter in Cuba" and "More Freedom But Not Free."

CT also has a special section on Cuba on our site, including:

Bearing the Cross: Freedom's Wedge |What you can do to help persecuted Christians. (October 7, 2002)

Cuba: After Castro | Church leaders worry that aid chaos will follow dictator's death (October 1, 2001)

Cuba's Next Revolution | How Christians are reshaping Castro's Communist stronghold. (January 12, 1998)