Job and his wife became Christians the same way most Chinese do: A friend who was visiting the couple in their home simply shared the gospel. “She came for 24 hours, and she preached the gospel for 20,” Job says of an evening five years ago.

This is how Christianity spreads in China: person to person. Until recently, churches didn’t sponsor public evangelistic outreach or anything else that officials might perceive as disrupting order.

As quickly as Job and his wife became Christians, the couple, both medical doctors and professors, encountered the biggest obstacle to Christianity in China. Where was the church? Job now knows there are plenty of churches in his city, but he knew of none five years ago. So under the advice of their friend, they started a Bible study. Within four months they had 100 attendees, and it was time to start a church.

Job was accustomed to working with government officials, security officers, and other influential people in his city of 7.8 million people. As a doctor, he regularly treated local Party officers. He saw no need for his church to meet clandestinely. Rather, Job met with officials monthly, keeping them informed of the church’s activities, even inviting them to Christmas and Easter services. Job and his wife now rent office space and do not hide the fact that it’s for church services.

Job is consciously avoiding the traditional approach that unregistered house churches once used. “The old house-church movement’s relationship with the government is confrontational,” he says. “We are looking at coexisting. For them to ask anything of us, we will look at it, and if it’s proper, we will do our best to cooperate.” Last Christmas, Job’s church, together with urban house churches across China, worked with local officials to deliver “parcels of love” to needy families.

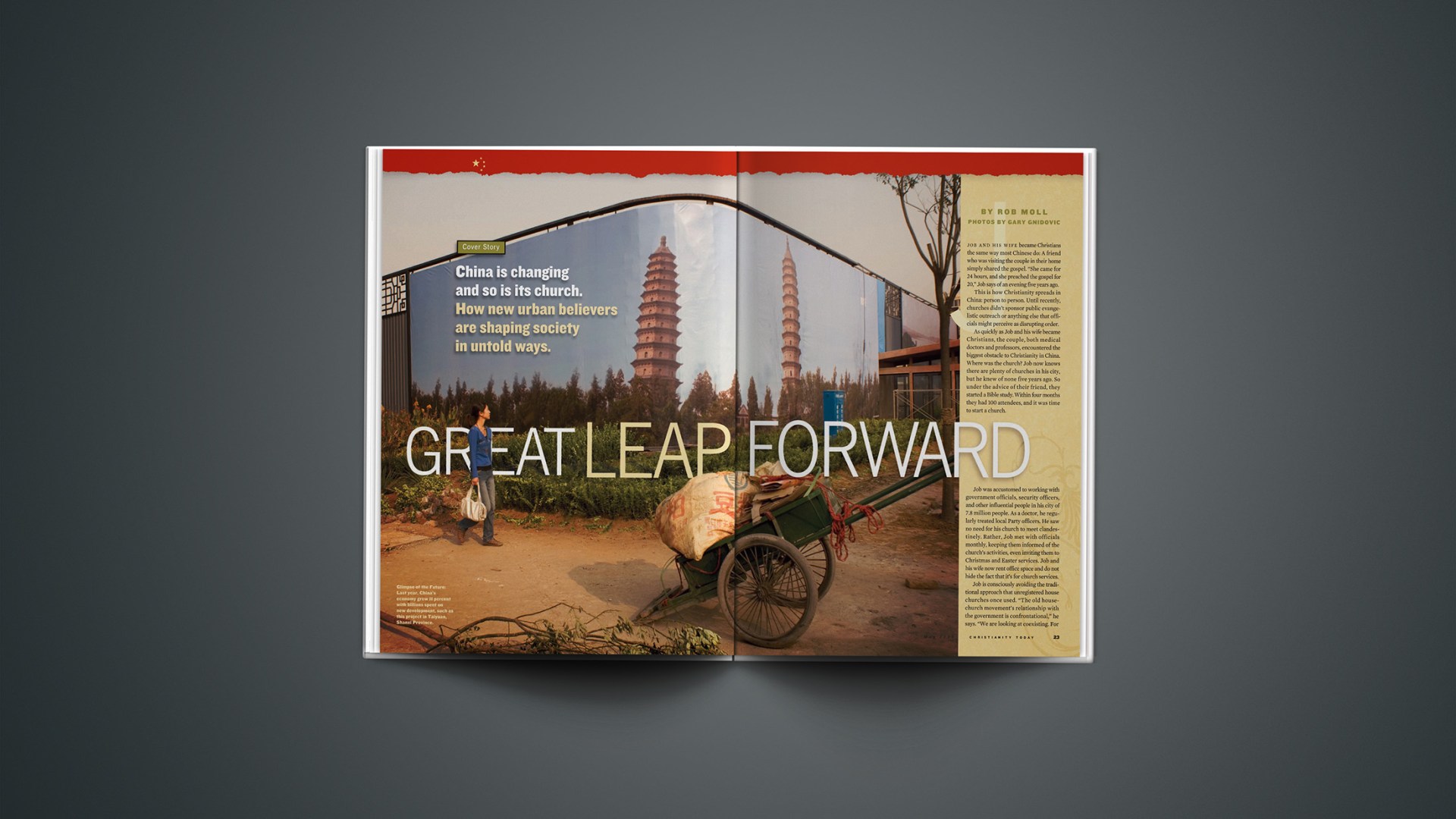

It’s a strategic gesture, a great leap forward for Christians eager to express God’s love for their neighbors. “Government acceptance of us depends on our community contribution,” says one pastor.

The success of these new churches, which have never been underground, is having a ripple effect on traditional house churches. “The churches are tired of hiding,” says John Davis, elder at the Beijing International Christian Fellowship, the city’s main church for English-speaking expatriates. “They have been hidden for so long. They are ready to rise up and be seen, to be salt and light in society.”

In Wenzhou, a southeastern city known as the Jerusalem of the Orient, urban church buildings are rising up like bamboo shoots. One Wenzhou pastor, known as Uncle Daniel, led his rural church as it morphed into an urban one as the city expanded. During that time, he became a business owner, and now drives an Audi and owns two homes. He says, “We are becoming both spiritual and sophisticated.”

Uncle Daniel is keenly aware of the poverty and persecution of the past, especially during the extremely repressive Cultural Revolution (1966–76), when Party officials banned all religious activity. He also knows the opportunities that have come as a result of the country’s spectacular economic growth. It has given Christians in China access to wealth, education, and influence, and they are using those advantages to make China a more welcoming place for Christian witness. Urban church members are taking the gospel not just to the rest of China, but across Asia and around the world as well. “We want to be part of the global church,” he says. “We want to be part of the reinforcement for world missions.”

The growing influence of Christians comes as a result of cooperating with the once, and sometimes still, brutally repressive government. “God has his eyes set on China,” Uncle Daniel says. “I am seeing that in the policy of the government. I am seeing that in the change of the politics and economics. I’m seeing change in our morality. I believe God will allow China to become strong not just for political reasons, but far more for his kingdom purpose.”

China’s human-rights track record remains poor. In mid-March, the U.S. government dropped China off its list of the 10 worst violators of human rights. But that same week, China launched a deadly crackdown against pro-democracy Tibetan protesters.

The Third Church

The dazzling growth of Christianity inside China began in the late 1970s at the end of the Cultural Revolution. During that period, up to 7 million people died from widespread violence and famine.

At that time, there were an estimated 3 million Catholics and Protestants in China. Three decades later, estimates of the number of Christians vary widely, anywhere from 54 million to 130 million, the higher number representing a 43-fold increase, which would be one of the largest growth spurts in the history of Christianity.

Scholars have debated for decades about the number of Christians in China. But the new estimates both come from government sources. The higher number of 130 million reportedly comes from Ye Xiaowen, the head of China’s State Administration of Religious Affairs. According to reliable reports, he used the 130 million head count at two government briefings in 2006. Bob Fu of China Aid Association has cited 130 million as a credible estimate. Other experts believe any statistic reporting over 100 million Christians is not credible.

The greatest new growth of Christianity is in urban areas. China’s economic explosion over the last 20 years has profoundly changed this country of 1.4 billion people, not least its Christians.

Many analysts now see three (often overlapping) groups of Christians inside China:

First, the official associations (subdivided into Three-Self Patriotic for Protestants, and Catholic Patriotic) that are registered with the government, which must approve pastoral, academic, and top-level administrative appointments.

Second, the traditional house-church movement that has rejected oversight and registration. It has been the strongest in rural areas. When the government loosened religious and economic restrictions starting in the late 1970s, the house-church movement exploded in size.

Third, the urban house church, which is not part of either the state church or the traditional “underground” church.

Along with Chinese Christians’ strong emphasis on church planting, several additional factors are driving huge changes in the makeup of Christians in China. First, rural Christians have moved to the cities, causing the growth of the once-burgeoning peasant Christian movement to level off. A second factor is the Chinese who have been educated overseas. As China opened up, many went abroad to study, and in the West, many became Christians. These students have returned to China with prized degrees from universities in America and Europe, and are ready to use their influence for the good of society and the church.

A third factor feeding Christian growth is Westerners who have taught English in Chinese schools. Through individual relationships, these teachers shared the gospel with their students, who became Christians and are now part of China’s elite.

A final factor is China’s moral vacuum. The Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989 left many people questioning government values. The killing of unarmed protestors destroyed China’s pro-democracy movement, but it also destroyed the nation’s soul, says one Chinese leader. As a result, the academic study of Christianity became a maverick discipline in intellectual circles and a curiosity for others.

A Turning Point

In April 2007, 70 leaders of the urban house-church movement gathered in Wenzhou to discuss their common identity and challenges.

The Hong Kong–based missions agency Asian Outreach, and particularly its former president David Wang, have taught many of these new urban leaders. At their conference last year, the leaders identified seven core values:

• Practice “kingdom first.” They acknowledge and work with other churches in each city and across China. Urban Christians, like most Chinese believers, are intentionally nondenominational.

• Be “Bible based.” Theologically, they are conservative and evangelical.

• Believe in the “five-fold ministries.” They acknowledge the roles of apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors, and teachers as spelled out in Ephesians 4:11.

• Equip the saints. Rather than relying on the emergence of charismatic leaders, they follow a mentoring model to disciple people.

• Receive the “abundant life.” While rejecting the prosperity gospel, they believe God can bless Christians materially, and that blessing can be used to influence others to build the kingdom.

• Desire to “establish the church.” They are missionary, including a strong desire to take the gospel “back to Jerusalem.”

• Seek “to bless the society.” They are newly engaged in social ministry.

While this movement existed 20 years ago, 2003 was a defining moment. That year, the release of the book Jesus in Beijing and The Cross video series exposed the house-church movement to the glare of public scrutiny and triggered new government crackdowns. But the book and videos also gave new credibility and influence to house-church Christianity.

One pastor in Guangzhou city says that “quite a lot” of the 400 members of his church are Communist Party members. Professors, doctors, lawyers, and business owners are now seeking more freedom as Christians, while also hoping to openly influence society with the values of the gospel.

Last October, Christianity Today spent two weeks in Hong Kong and Beijing speaking with many of the leaders of this urban church movement. While many of these leaders were eager to tell Western Christians of their new freedoms and growing churches, they still operate in a gray area, legally speaking. Much of their activity has been considered illegal in the past, and though the government seems to be loosening restrictions, churches have no guarantee this will last.

Indeed, while CT was in country, a high-profile Christian human-rights lawyer was beaten and arrested, and church leaders were jailed. As a result, most of those interviewed asked to remain anonymous. As much as things have changed in China, much remains the same.

God, the Party, and Freedom

Hsu, a former television journalist for the state-sponsored CCTV, is a telling example of how a member of China’s educated elite moves to Christianity.

Hsu told his story to CT over a meal at a crowded Beijing KFC. It began with his search for freedom—politically and personally. The search led him to European history. “Westerners are not more interested in freedom than anyone else,” he says.

Yet the West has achieved and sustained a greater degree of liberty than any other culture. Hsu wondered what the West had that China didn’t. “Before freedom comes, you have to have a foundation. In the West that foundation is Christianity.”

Hsu’s vision for a new China parallels his readings on the march of freedom in the West. From the 10th to 12th centuries, Hsu reasons, Europe developed legal studies, hospitals, and universities, all of which grew out of the church. These developments resulted in breakthroughs in human liberty, as seen in the Reformation, the Renaissance, and the Enlightenment. Today, Hsu says, the church is an incubator for similar developments in China.

“After the country adopted Western science and philosophy, it left a value vacuum,” Hsu says. “After Tiananmen Square, some scholars lost hope. They wanted to start asking the ultimate questions about the purpose of life. People in China have lost faith in human wisdom. The Cultural Revolution was a disaster, but this spiritual awakening is an unexpected result.” Hsu’s quest led him to the Bible. There, he learned that “faith in God as the Lord is the beginning of freedom.”

Recently, he delivered a paper on freedom to a local gathering of the American Political Science Association. In it he wrote, “The more I knew about the growth of freedom in the West, the more I was captivated by the role of faith in God as the Lord.”

“You need a standard of absolute truth,” Hsu told CT. “You have to convince people that the God of the Jews and Christians is the God of the universe.”

For Hsu and those like him, the hope of the Chinese church is not political change. “The essence of the problem is human salvation,” he says, “not politics.” Hsu wants Western liberty in his own country, seeking its growth through the development of China’s civil sector, something Christians are creating anew (it having been lost in the Cultural Revolution). Hsu says churches are starting orphanages and community centers, youth activities, and marriage seminars.

But Hsu counsels patience, noting that such advances in the West took centuries to develop. “In China, it will take the same kind of time.” Observers say China is already changing its policies on religion. At the latest National Party Congress, held every five years, the highest Communist Party officials gathered to chart China’s future. In a lengthy two-and-a-half-hour address, President Hu Jintao delivered this line:

“We will fully implement the Party’s basic principle for its work related to religious affairs and bring into play the positive role of religious personages and believers in promoting economic and social development.”

China observers believe this is a significant shift. Five years ago, officials said the government would “encourage the adaptability of religions to the Socialist society.” About Hu’s speech, one China analyst told CT, “Such an explicit recognition of religion’s potential to positively contribute to society hasn’t been made before.”

Today, it is not unheard of to find Christians within the Party. Jesson Tian grew up in the hometown of Confucius, and before he entered college, his father encouraged him to join the Party. Jesson was accepted for Party membership. But while in college, he became a Christian.

If forced to choose between his faith and his political loyalties, Tian said he would choose his faith. But he sees no contradiction. “Every time I share the gospel,” he says, “I say, ‘I’m a member of the Party.’ They are surprised, but I think they will trust me more.”

Tian worships occasionally at a house church as well as at the Beijing Three-Self church, Haidian, which reopened last May in a new building with tall white pillars. “The government supported Haidian church’s new building,” Jesson says. “The government is part of the church. The government controls the church, not to take charge, but to be a part of it.”

Lack of Social Balance

In Hong Kong, ministry leader David Wang looks across the cafeteria of the Ecclesia Bible College. More than 70 urban church leaders from across China have gathered to study the Holy Spirit’s role in the New Testament.

But Wang’s thoughts are already on the ministry horizon. He discusses future training events with two New Zealand pastors. He asks, “Can you teach about the Great Commandment?”

Wang explains that the rural house church, hiding and persecuted, has developed its evangelistic muscles, but that it’s still weak in “love-your-neighbor” care for society. The urban church, he says, is eager to learn more about ministry outreach. Its members know the church gains legitimacy—and thus opportunities to witness—by being good citizens.

Max Wang, a seminar leader in Beijing, shares a telling example of this dynamic. In 1997, he became a Christian. Within a few months, he was leading a Bible study group. A few years later, he was reading John Ortberg’s If You Want to Walk on Water, You’ve Got to Get Out of the Boat. Inspired, he quit his job to become a full-time pastor.

Max concentrates on community development. On Saturday afternoons in the high-rise residences of Beijing, he holds seminars on marriage, parenting, physical and mental health, management, and finance. His dream is to have seminars in every one of Beijing’s high-rise residences.

He says that economic prosperity has brought twin social evils—divorce and official corruption—and that young people only care about money and career success. “The government has only paid attention to the economy,” Max says. “That is unbalanced.

“Only Jesus can make a harmonious society,” Max adds. “We don’t preach the Bible, but people are free to do that at home.” Max says a high rate of participants in his seminars become Christians.

Christians are also influencing the fields of law and economics. Ark Church in Beijing is home to several influential lawyers working to advance human rights in China. Two lawyers were part of a group that met with President Bush in May 2006.

One member of that group, a writer, explained to a reporter, “Our church wants social equality. And we happen to have a lot of lawyers, so they can provide free services to people who have suffered harm, whether or not they are Christian.”

Zhao Xiao is a young, highly influential economist who has gained a reputation for arguing that China’s economy needs Christianity. He wrote an essay in the Chinese edition of Esquire magazine entitled, “God Is My CEO,” and a more academic paper, “Market Economies With Churches and Market Economies Without Churches,” which was published before Zhao became a Christian. He is the former director of the macro-strategy department at the research center of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, an adviser to China’s Central Committee.

During a recent visit to the U.S., Xiao told CT that Christianity is the backbone of Western economic success. “Christian faith provides the power for economic growth. Everybody wants to make more money, from the ancient time till now. And from history we see that only Christians have a continuous creative spirit and the spirit for innovation.”

A Visible Model

China’s vast population has many ethnic subgroups. The 2 million or more ethnic Korean Chinese, mostly in the northeast, are turning to Christ in significant numbers.

In fact, the largest public gathering of unregistered Christians has an ethnic Korean pastor, and he is an impatient innovator. Pastor Quan attended David Wang’s training session in Hong Kong, but after days of intensive instruction, he was visibly on edge while sitting in a student lounge. A major building project at his church was under way, and it was constantly on his mind.

Quan wants to adapt Korean church-growth ideas to China’s house churches. (Korea has some of the largest churches in the world.) He plans to make his 700-member congregation into a model for the rest of China’s urban churches.

The traditional house church has always been small, subdividing itself frequently. Church members bring their friends to church and it grows. If a house church gets too large in China, it attracts attention and often runs out of room to continue growing. So when a church reaches around 100 people, it splits. Quan argues this traditional model spread the gospel, but didn’t spread Christian influence. “I think the church should grow,” Quan says. “So I bought a factory, then a hotel, then built my own building.”

Over the last few years, he says, “I’ve learned one important thing. Church growth has nothing to do with the government or the environment. It has to do with the enthusiasm of the gospel.”

He believes his growing congregation will evolve into a “flagship” for creative church growth. Quan, a graduate of a Three-Self seminary, believes government officials will be tolerant of his ambitious project. “I think the government wants healthy, normal growth that spreads the gospel and blesses society. For this kind of church, the government will relax its regulations.”

He sees problems with the existing house-church model. “They are teaching in conflict with each other. They are confused, marginalized, and not transparent,” Quan says. Cults, charismatic leaders, and aberrant teachings have devastated many house churches.

With the resources of a large church, Christians can visibly operate and be a blessing to others. Quan tells CT, “If we don’t go mainstream, what’s the point? Urban churches must have an open assembly, a visible model.”

Other leaders are pursuing these same goals. In Beijing, one house church opened in June 2007 in a building next to a nightclub. When CT visited in October, the church had 220 people attending. “There’s still some risk to coming out,” said the pastor as he brewed tea in his office. “But when people can worship openly, they like it.” One of the biggest draws the church has is an electric guitar.

Elsewhere in Beijing, Quan and his partners run six Christian bookstores. One, set on the ground floor of one of the city’s high-rise residential buildings, holds 2,000 volumes, videos, and art. Every book has been approved for publication by the government, though the store itself has received no such approval. Books by C. S. Lewis, Gary Smalley, and Robert Schuller sit beside volumes of theology written by Chinese theologians and published by exclusive academic presses.

Quan and his partners estimate that between 180 and 200 Christian bookstores have opened in the last four years. He trained many of the owners. The store is more than a place for Christians to buy spiritual literature: at one bookstore next to a university, Quan says new people turn to Christ almost every day.

From China Back to Jerusalem

Following the Cultural Revolution, David Wang says, China ministry meant ministry to China. Years ago, Wang broadcasted readings from Streams in the Desert into China twice daily. Others smuggled Bibles or simply prayed. As China opened up in the ’80s, it became ministry in China. English teachers became the face of that ministry.

In the 1990s, Wang discovered the traditional house church was like the Book of Acts, with signs and wonders. “But they were drifting very fast into the church of Corinth, with corruption and immorality.”

Wang felt it was time for ministry with China. “Eugene Peterson’s teaching of spirituality as being real in Christ, allowing Christ to be real in you, became the hallmark of my training in China.”

Today, Wang says, the church is more mature. “I see these young leaders. They are preparing their co-workers to come out of China. I see the young leaders from the house church in China planting churches in southern Europe, western Europe, and Calgary and Toronto. I see them everywhere. So it’s now the era of ministry from China.

“We the Chinese church are the ones who are going to bring the gospel back to Jerusalem,” he says. “Probably every one of these leaders has been to Jerusalem. Why? Because somehow this crazy Chinese church could never forget that if we could bring the gospel back to Jerusalem, we will complete Matthew 24:14—that this gospel must be preached around the world. So we Chinese have the mandate to complete the gospel circle and usher in the return of Jesus.”

The “back to Jerusalem” movement is capturing the imagination of new believers. The owner of an automotive-parts factory in east-central China is a case in point. Four years ago, the factory owner, Ruth, gave her life to Christ.

A devout Buddhist, she had been hearing a voice in her mind telling her to believe in Jesus. “I wasn’t willing to listen,” she says. Eventually she asked a business associate who had once told her about Jesus to tell her more. “That evening I decided to believe in Jesus.”

Today, not only does Ruth pastor a church that meets in her factory, but all of her employees are Christian. And all are in training to be missionaries. This year, Ruth plans to open a factory on China’s border with Pakistan. Her employees will move there and run the business, which will fund a missionary outreach. She plans to do the same thing inside Pakistan, then Iran, and eventually Jerusalem.

It takes more than evangelical fervor to successfully operate a missionary enterprise, and it’s yet to be seen if the efforts of individuals like Ruth will be able to carry the gospel to one of the most gospel-resistant regions of the world. But everything that happens in China does so on a grand scale.

Less than 50 years ago, Party members talked not only of God being dead, but also of his burial in China. Now Party members like Jesson Tian are comfortable practicing their faith and evangelizing, while being loyal citizens of this officially atheistic country. “I love the Party,” he says. “It saved us from the war, from starvation, from disease. But I love God more, because he made all things himself.”

Rob Moll is a CT editor at large.

Copyright © 2008 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Our May 2008 China coverage also includes:

Hungry for Jesus | A Chinese pastor on how he was ‘called out of Egypt’ to a thriving urban ministry. (May 9, 2008)

Inside CT: The China Paradox | ‘Embattled and thriving’ Christianity in China. (May 9, 2008)