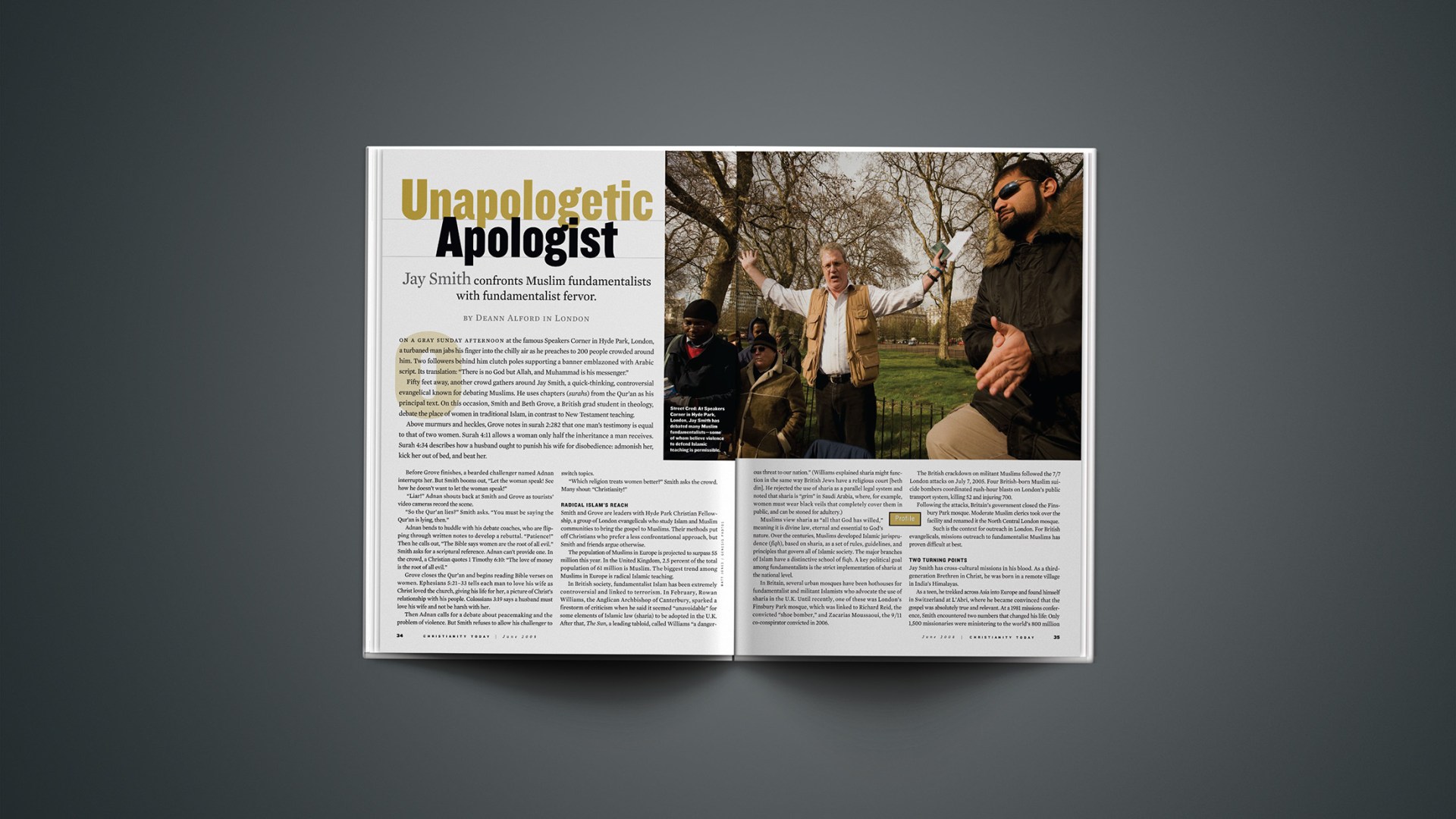

On a gray sunday afternoon at the famous Speakers Corner in Hyde Park, London, a turbaned man jabs his finger into the chilly air as he preaches to 200 people crowded around him. Two followers behind him clutch poles supporting a banner emblazoned with Arabic script. Its translation: “There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is his messenger.” Fifty feet away, another crowd gathers around Jay Smith, a quick-thinking, controversial evangelical known for debating Muslims. He uses chapters (surahs) from the Qur’an as his principal text. On this occasion, Smith and Beth Grove, a British grad student in theology, debate the place of women in traditional Islam, in contrast to New Testament teaching.

Above murmurs and heckles, Grove notes in surah 2:282 that one man’s testimony is equal to that of two women. Surah 4:11 allows a woman only half the inheritance a man receives. Surah 4:34 describes how a husband ought to punish his wife for disobedience: admonish her, kick her out of bed, and beat her.

Before Grove finishes, a bearded challenger named Adnan interrupts her. But Smith booms out, “Let the woman speak! See how he doesn’t want to let the woman speak!”

“Liar!” Adnan shouts back at Smith and Grove as tourists’ video cameras record the scene.

“So the Qur’an lies?” Smith asks. “You must be saying the Qur’an is lying, then.”

Adnan bends to huddle with his debate coaches, who are flipping through written notes to develop a rebuttal. “Patience!” Then he calls out, “The Bible says women are the root of all evil.” Smith asks for a scriptural reference. Adnan can’t provide one. In the crowd, a Christian quotes 1 Timothy 6:10: “The love of money is the root of all evil.”

Grove closes the Qur’an and begins reading Bible verses on women. Ephesians 5:21–33 tells each man to love his wife as Christ loved the church, giving his life for her, a picture of Christ’s relationship with his people. Colossians 3:19 says a husband must love his wife and not be harsh with her.

Then Adnan calls for a debate about peacemaking and the problem of violence. But Smith refuses to allow his challenger to switch topics.

“Which religion treats women better?” Smith asks the crowd. Many shout: “Christianity!”

Radical Islam’s Reach

Smith and Grove are leaders with Hyde Park Christian Fellowship, a group of London evangelicals who study Islam and Muslim communities to bring the gospel to Muslims. Their methods put off Christians who prefer a less confrontational approach, but Smith and friends argue otherwise.

The population of Muslims in Europe is projected to surpass 55 million this year. In the United Kingdom, 2.5 percent of the total population of 61 million is Muslim. The biggest trend among Muslims in Europe is radical Islamic teaching.

In British society, fundamentalist Islam has been extremely controversial and linked to terrorism. In February, Rowan Williams, the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury, sparked a firestorm of criticism when he said it seemed “unavoidable” for some elements of Islamic law (sharia) to be adopted in the U.K. After that, The Sun, a leading tabloid, called Williams “a dangerous threat to our nation.” (Williams explained sharia might function in the same way British Jews have a religious court [beth din]. He rejected the use of sharia as a parallel legal system and noted that sharia is “grim” in Saudi Arabia, where, for example, women must wear black veils that completely cover them in public, and can be stoned for adultery.)

Muslims view sharia as “all that God has willed,” meaning it is divine law, eternal and essential to God’s nature. Over the centuries, Muslims developed Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), based on sharia, as a set of rules, guidelines, and principles that govern all of Islamic society. The major branches of Islam have a distinctive school of fiqh. A key political goal among fundamentalists is the strict implementation of sharia at the national level.

In Britain, several urban mosques have been hothouses for fundamentalist and militant Islamists who advocate the use of sharia in the U.K. Until recently, one of these was London’s Finsbury Park mosque, which was linked to Richard Reid, the convicted “shoe bomber,” and Zacarias Moussaoui, the 9/11 co-conspirator convicted in 2006.

The British crackdown on militant Muslims followed the 7/7 London attacks on July 7, 2005. Four British-born Muslim suicide bombers coordinated rush-hour blasts on London’s public transport system, killing 52 and injuring 700.

Following the attacks, Britain’s government closed the Finsbury Park mosque. Moderate Muslim clerics took over the facility and renamed it the North Central London mosque.

Such is the context for outreach in London. For British evangelicals, missions outreach to fundamentalist Muslims has proven difficult at best.

Two Turning Points

Jay Smith has cross-cultural missions in his blood. As a third- generation Brethren in Christ, he was born in a remote village in India’s Himalayas.

As a teen, he trekked across Asia into Europe and found himself in Switzerland at L’Abri, where he became convinced that the gospel was absolutely true and relevant. At a 1981 missions conference, Smith encountered two numbers that changed his life: Only 1,500 missionaries were ministering to the world’s 800 million Muslims, a missiologist reported.

“Fifteen-hundred wouldn’t do diddly-squat,” Smith said. So he threw himself into apologetics and specialized in Islamic theology. Following graduation from Fuller, Smith grew a bushy beard, learned to speak French in Paris, and headed off to French-speaking Senegal, eager to engage Muslims.

Four years later, an urgent message from a London missionary redirected Smith’s focus. This friend was doing a door-to-door survey on religion and found that the average Brit cared little about faith. This researcher’s most dynamic religious conversations were with Pakistani and Indian Muslims. And this colleague uncovered a troubling trend: an increasingly radical Islamic element that Britain’s Christian leaders were apparently unaware of, let alone doing something about. He urged Smith to come to London. Smith agreed.

Soon after arriving in 1992, Smith visited Speakers Corner, where hundreds of Muslims converged each Sunday to hear virulent Islamic preachers.

At times, 10 passionate Islamic speakers, using a short ladder as a platform, roused equally passionate crowds of men in native dress, all punching the air, shouting “Allahu akbar.” These individuals were imams or educated men of high standing. Women also attended. Combative free-for-alls between followers of different Muslim clerics erupted on occasion.

Smith decided to step right up and start speaking to the crowd. But he didn’t get far. The crowd laughed at him. They pushed, punched, and cursed him, and yanked his beard (since shaved off).

“I was not expecting vitriol, aggression, physical abuse,” Smith says. “This was way out of my comfort zone.” Smith found addressing Muslims’ objections to Christianity next to impossible. These adept debaters responded with challenges that Smith’s years of apologetics and seminary studies had not prepared him to confront.

“Christians had all the best material but didn’t know how to package it,” Smith says. To reach Muslims, he needed a better way to communicate. “I just felt I didn’t know the material well enough. Muslims had much better presentation.”

Learning to Argue

Smith admitted to himself that he had mastered Islamic beliefs, but not Islamic culture.

Passionate presentation is one key to reaching Muslims, he felt. Many will not be convinced, he believes, “unless we look like we believe what we’re saying.”

Western seminaries taught Smith “friendship evangelism” as the primary way to share Christ with Muslims. Nothing should offend. Never point out contradictions, inconsistencies, or historical inaccuracies in another person’s religious beliefs. Everything aims to convert. Judge results by the number of conversions.

Smith decided to take an alternate approach:

- Defend historic, orthodox Christianity.

- Answer untruths that Islam proclaims about the Bible, Jesus, and Christians.

- Hold Islam itself accountable for the actions of its followers.

“We have to start taking Christ back to his Mediterranean roots,” says Smith. “True love confronts friends when they go wrong. Paul certainly argued. Jesus certainly argued. That’s the kind of love Muslims need to hear.

“Propositional truth confronts,” he argues, in fundamentalist fashion. “If there’s not a reaction, we’re not preaching the gospel.”

In most Muslim-Christian dialogue, Smith believes Christians typically concede on points of orthodox doctrine to make the faith palatable to Muslims. Smith asks: Why should Muslims respect any Christian who distances himself from what he claims to believe?

“I refuse to spend my time talking about the weather, talking about politics, unless the gospel is introduced,” Smith says. “The gospel by definition is confrontational. I absolutely want to stop Islam because Islam is stopping these people.”

Over the years, Smith immersed himself in the Muslim community, building relationships with Muslims in mosques and teahouses. He heard a recurring theme: Christianity is to blame for the moral, spiritual, and economic decline of the West. “Islam is the answer,” many would say, echoing the political slogan of the Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt’s infamous fundamentalist Islamic group.

Through years of trial and error, Smith trained himself in debate, apologetics, polemics, and presentation. He studied the Qur’an and the Bible, developing responses to Muslims’ objections to Christianity. “I was scared to death of getting on the ladder, making a fool of myself,” Smith says.

Foolishness didn’t seem to be the problem; not surprisingly, continued hostility was. For example, in 1995 a Muslim boxer knocked Smith unconscious. He’s also been assaulted with a knife, and has received many death threats. Overall, being on the ladder forced Smith to polish his delivery—faster, louder, and “a lot more eloquent.”

Smith’s approach remains controversial not just for Muslims, but for Christians as well.

Christian experts in Muslim outreach note that Smith’s approach is highly specialized and would work better in Western nations, not Muslim-majority countries. (Smith agrees.) But his methods are similar to the debate strategy that Father Zakarias, a Coptic Orthodox priest, uses on Arabic-language television and GodTube.com, both available in North Africa and the Middle East.

Roy Oksnevad, director of Muslim Ministries at the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College, told Christianity Today, “People like Father Zakarias and Jay Smith play a role. They hold up orthodox Islamic teaching that is not popular to hold in the international community. They are central teachings of Islam.

“This exposure is viewed as a threat and often viewed by Muslims as trying to subvert Islam. People like Jay Smith play an important role in talking about the problem in open forums that very few want to talk about.”

Another scholar, Joseph Cumming, director of the newly developed Reconciliation Program at the Yale Center for Faith and Culture, told CT that Smith and Hyde Park Christian Fellowship have done much valuable research. But if the goal is to bring urban Muslims to Christ, Cumming said that Smith’s method of criticizing the Qur’an is not nearly as effective as exclusively giving “the positive message of Christianity.” Cumming said Smith’s methods might prove more beneficial to the church in keeping nominal Christians from converting to Islam.

Smith has now become something of a celebrity in the Islamic world. At the Oxford Union and other venues, he has had 40 formal debates on subjects such as whether Islam is compatible with the West, and who the real Jesus is. His debate opponents have included Benazir Bhutto, the former Pakistani prime minister assassinated in late 2007, and Sheikh Omar Bakri Muhammad, one of the most well-known Muslim fundamentalists and allegedly a spiritual mentor for Al Qaeda terrorists. (Bakri is currently under arrest in Lebanon.)

Training Others

In recent years, Smith has begun training Christian leaders in debate strategies. While Smith has a deserved reputation for confrontational evangelism, there is more going on in his approach.

Smith said he advises Christians, “Make sure you’re not bashing Muslims. Never say Muslims are evil. They’re just like you and me.

“I have no problem with Muslims. We think they are terrific. It’s the Qur’an we have problems with.” Smith is known to pat his Muslim friends on the back, exchange cordial greetings, even coach them in debate techniques. The website of Hyde Park Christian Fellowship (debate.org.uk) offers free website space to Muslims, granting them “the right to reply” to Christian arguments. “We take Muslims seriously and acknowledge their right to argue their case,” the site says.

The new relationships with young, passionate Muslims that develop at Hyde Park Christian Fellowship can have a tragic dimension. One fellowship member befriended a Pakistani Muslim, Asif Hanif, described as a “gentle giant.” This member visited Hanif’s London home, met his parents, and attended a Muslim gathering with him.

One day, Hanif abruptly left London, supposedly to learn Arabic in Syria. But in April 2003, Hanif blew himself up in Tel Aviv, killing three Israelis. British fundamentalists praised Hanif’s suicide bombing. Afterward at Speakers Corner, Smith asked who among them supported Hanif’s actions. Thirty hands were raised. “How many would do the same in London?” Smith asked. Fifteen hands went up.

Hyde Park Christian Fellowship was founded in 2000 and currently has about 40 active members. The group, mostly students and other evangelicals in their 20s, visits Speakers Corner with Smith. Christians are often outnumbered 9 to 1 and have strict rules. “We don’t allow any of our people to fight, even if hit,” Smith says. The Sunday debates frequently play off current events, such as Pope Benedict XVI’s comments on Islam or the publication of Danish cartoons of Muhammad. Peace is a staple topic.

After sunset, fellowship members regroup nearby at a restaurant that Muslim regulars at Speakers Corner also frequent. Smith and his Muslim friends greet one another, sometimes dine together, and engage in deeper spiritual conversation. One of these friends whom Smith meets is named Mahdi. Even though Jesus has appeared to Mahdi in two dreams, he professes he will never leave Islam.

Smith also hosts advanced study groups. One is called “Codgers,” designed to train Christian debaters; another is SWAD (Scholars With a Dream), which conducts doctoral-level research on Islam.

Smith helped create the Pfander Center, which prepares missionaries for ministry among Muslims. The name Karl Gottlieb Pfander is rarely mentioned today among Christians, but Islamic historians know it well. In Agra, India, 154 years ago, Pfander debated a Muslim theologian (Rahmatullah Kairanawi) for two days of high drama on the integrity of the Bible. Both sides claimed victory afterwards.

Partly due to this debate, Protestant missions gained greater credibility among Muslims and Hindus inside colonial India, and two high-profile Indians from a Muslim background were baptized less than 10 years later.

On YouTube, Smith has a collection of videos he calls “Pfander Films” in honor of the German missionary. These films, 62 and counting, have collectively received more than 450,000 views. One video, titled “Who Hijacked Islam?” received 29,000 hits in a 12-month period.

Smith invites other Christians to join him. “If we really want to see radical Islam brought to its knees, some of us are going to have to move beyond everything we have been taught,” Smith wrote in a 2007 prayer letter.

“Rather than simply seek after converts, we must roll up our sleeves and engage publicly and passionately, knowing that we won’t initially see many converts. Down the road, we will certainly find hundreds—no, millions—brought home.”

His influence has begun to ripple into European evangelical missions. One Brussels-based missions leader spent time with Smith at Hyde Park. Via e-mail, this leader told CT that Hyde Park Christian Fellowship is “a place to go for help in unmasking Islam if it is needed in a particular case.”

The leader now supports a more straight-talking, bolder kind of Christian witness for urban Europe. He wrote, “It is better to be straightforward (and loving) about what we believe than to be overly careful. I think more people ache for authenticity than what we want to imagine.”

On occasion, Smith hears that the fellowship’s work has brought a Muslim to Christ. A few years back, an Iraqi hospital administrator received a copy of a Smith paper challenging Islam. After careful examination, the administrator was persuaded and gave his life to Christ. Today, he works in Muslim outreach. “You won’t find people of that caliber unless you go after the best and brightest,” Smith says.

Smith maintains the church is uniquely able to confront Islamic teaching. “The only way to deal with this radical form of Islam,” he asserts, “is with an equally radical form of Christianity.”

Deann Alford is a senior writer for CT and lives in Austin, Texas.

Copyright © 2008 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Videoclips of Jay Smith in action are available on YouTube.

Hyde Park Christian fellowship’s debate site has more about the organization’s purpose.

Previous articles about Islam and Christianity are in our special section on other religions.