Don’t let the title fool you. The Last King of Scotland takes place not in the Highlands but in Uganda, and the title refers not to some European monarch but to one of the most notorious African dictators, Idi Amin. So why do this film—and the Giles Foden novel on which it is based—bear this title? Partly because “King of Scotland” was one of the many titles Amin gave himself during his brutal eight-year reign; another was “Conqueror of the British Empire.” Amin, who rose through the ranks of the British colonial army under the patronage of Scottish officers before Uganda became independent, was a fan of all things Scottish, and sometimes wore kilts in public.

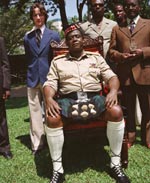

The film is also told from the point of view of Nicholas Garrigan (James McAvoy, last seen as Mister Tumnus in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe), a Scotsman who has just earned his medical degree, and who goes to Africa to get away from his stern father and to have some “fun”—having sex with total strangers, treating the odd patient, and soaking in the anti-English, anti-colonial atmosphere. When Nicholas first arrives in Uganda, he hears that Amin has just taken over the country in a coup, but the locals tell him not to worry; and the first time he sees Idi Amin (Forest Whitaker) himself, at a political rally surrounded by supporters and tribal dancers, he is impressed by the leader’s charisma.

At this point, Garrigan is working at a mission with a pair of doctors whose marriage seems to be a little strained, and for a while, Garrigan befriends and even tries to seduce the female half of this couple (The X-Files‘ Gillian Anderson). But an unexpected roadside encounter with Amin, his bodyguards, and a wounded cow quickly sends Garrigan’s life spinning in another direction. Amin, impressed by the foreigner’s willfulness—and by his Scottishness!—makes Garrigan his personal physician, and treats him to all the pleasures that come with high office.

Ironically, because he is so close to Amin, it takes Garrigan a while to realize the extent to which Amin is, in fact, a murderous tyrant. The dictator, as played by Whitaker, is so disarmingly amusing at first—swapping shirts with Garrigan, teasing him about his hair, even asking him to ensure that no one else will hear about an embarrassing minor ailment or two—that it takes some time to notice the menace lurking beneath the smile. There are moments of violence, both distant and up close, but Garrigan accepts the explanation that the blame for this lies with the previous ruler, who he never knew. A British diplomat (Simon McBurney) warns Garrigan that Amin is worse than he seems, but Garrigan dismisses the information, convinced that the English are just making it up because they resent losing their Empire.

But then Amin crosses that line that separates the amusing from the truly insane. His declaration that he cannot be killed because God revealed to him the day that he would die is one thing—a harmless show of confidence, perhaps—but then he declares that God has told him to expel all Asians (mostly Indians) from Uganda, a racist act that devastates the country’s economy. Eventually, even Garrigan can no longer avoid the fact that Amin is responsible for a series of utterly barbaric atrocities—and by then, Garrigan is basically trapped and afraid for his own life.

The Last King of Scotland is reminiscent of All the King’s Men, at least insofar as both films concern a son of privilege who forsakes his upbringing and hooks up with a charismatic leader from the lower classes—only to find that the new boss is at least as bad as the old bosses. The difference is, Garrigan is a much shallower figure; instead of an idealist who witnesses the corruption of everything he held dear, he is a hedonist who is confronted by the depths of his own self-centered naiveté.

This film marks the first dramatic feature from director Kevin Macdonald, whose work so far has been in the field of documentaries; he won wide acclaim for Touching the Void, a film about a hiking accident that could have turned out much, much worse than it did, as well as an Oscar for One Day in September, a riveting account of the Munich Olympics hostage crisis. (Incidentally, one narrative element that is common to Scotland and September is Palestinian terrorists who sought refuge in Africa.)

Macdonald brings a documentary sensibility to The Last King of Scotland, shooting almost the entire film in Uganda; at the Vancouver International Film Festival, he said it was the first film to be shot in that country in years, maybe ever, and it even makes use of the actual limousine and swimming pool that Amin himself once used. Cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle, who has worked on recent films by Danny Boyle (Millions) and Lars von Trier (Dogville), employs a sometimes jerky hand-held style that accentuates the realism and creates a sense of foreboding instability.

The performances are universally strong, as well—though the film’s documentary-like realism is arguably hampered by the fact that the story revolves around a fictitious character like Garrigan, who not only witnesses Amin’s historical deeds, but becomes actively, if unintentionally, involved in making them happen.

Yes, one of Amin’s wives met the gruesome fate depicted here, but her reputed lover at the time was a doctor named Mbalu Mukasa. And yes, Amin’s reputation (glossed over by foreign journalists who enjoyed his press-conference shtick) took a serious blow in the late 1970s, when an insider wrote a book about him—but that insider was Henry Kyemba, a former health minister. In this film, on the other hand, a black colleague tells Garrigan he wants to help him escape the country so that he can tell the world what Amin is really like: “They will believe you, you are a white man.” So for all the film’s post-colonial subtext, it does little to challenge the idea that the stories that matter are the ones in which the white man takes centre stage.

Talk About It

Discussion starters- Do you think Garrigan learns anything over the course of this story? About Uganda? About himself? What does he learn? Do you think he becomes a better person? What responsibility does he bear, if any, for the atrocities he witnesses

- Do you think the film explores the politics of that time deeply enough? Why do you think the film makes so much of the main character’s Scottishness? How are the British portrayed? Good, evil, or a mixture? What kind of mixture

- Why do you think Idi Amin is so fascinated with Scottish culture, even as he celebrates the rise of African culture?

The Family Corner

For parents to considerThe Last King of Scotland is rated R for some strong violence and gruesome images (including scenes of execution, ambush attacks, dismembered human bodies, and an animal being put out of its misery), sexual content (including male and female nudity) and language (about a dozen f-words, and a few instances of swearing.) Two characters also talk about getting an abortion.

Photos © Copyright Fox Searchlight

Copyright © 2006 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

What Other Critics Are Saying

compiled by Jeffrey Overstreetfrom Film Forum, 10/12/06Director Kevin Macdonald, who brought us the survival story Touching the Void, dramatizes the murderous malevolence of the Ugandan dictator Idi Amin in his adaptation of Giles Foden’s novel The Last King of Scotland.

James McAvoy—the actor who played Mr. Tumnus in The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe—stars as a misguided Scotsman who becomes Amin’s personal physician. But the film’s strongest virtue is the performance by Forest Whitaker as the dictator.

While Scotland gives us a behind-the-scenes look at Amin’s turbulent reign, critics aren’t exactly sure if anything profound is revealed in the process.

David DiCerto (Catholic News Service) says the film “serves as an indictment of inhumanity and hatred wrapped in a fairly compelling parable that asks: What does it profit a man if he gains the whole world—let alone a palace in Uganda—and loses his soul?” He praises Whitaker, saying that he “captures both Amin’s magnetism and megalomania, manically flipping between charm and rage and investing even a subtle eye flutter with deadly meaning. The result is a fascinating, if terrifying, portrait of monstrous cruelty that demands attention come Oscar time.”

Mainstream critics are impressed by the performances, but not so enthusiastic about the film itself.

from Film Forum, 11/16/06 “I’ve written many times before about how irritating it is that movies about Africa usually tell their stories through the eyes of white people,” says J. Robert Parks (Framing Device). “As if American audiences won’t bother with a movie that’s actually about African people. The Last King of Scotland adds to that cliché by emphasizing the strangeness of the continent. With only one exception, Africans are either monsters or saints.”

from Film Forum, 11/30/06 Sister Rose Pacatte F.S.P. (Eye on Entertainment) says, “Forest Whitaker’s stellar embodiment of the despot [Idi Amin] chills, convinces and deserves Oscar consideration. Scottish director Kevin Macdonald has crafted a masterful tale of Africa, calling us to pay attention to this suffering, emerging Third World land.”