|

Take a mother camel with a heartbreaking case of post-partum depression. Add—slowly—her wobbly rejected newborn, and a family of resilient shepherds who will go to great lengths to make the mother accept her child. Set them all in Mongolia’s arid Gobi desert where a TV set costs, oh, maybe 20 to 30 sheep, and the splendorous sight of sun setting over the brushed horizon seems to stop time. Let the camera linger, as does every minute of life in this far-off land. If it’s a true story—better yet, one caught as it unravels—you’ve got yourself a visual oasis that will rest eyes wearied of choosing in the land of plenty.

This is the fine idea of Mongolian-raised filmmaker Byambasuren Davaa, inspired by a drama she saw as a girl, one that depicted an old Mongolian legend in which nomadic herders reunite a mother camel and a baby she’d rejected. Some legends are true, of course. Knowing that the story—according to which an ancient musical ritual can undo a mother camel’s rejection of her colt—is based in reality, Davaa partnered with Luigi Falorni to direct the old fable playing out in real life. For their seemingly natural and simple cinematography, the two credit as their teacher the vanguard documentary maker Robert Flaherty (Man of Aran, Nanook of the North).

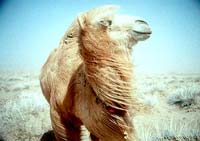

At the time when camels are having their young ones and nothing but a sand storm interrupts the herders’ watchful care over them, the filmmakers took their crew to the Gobi desert. Fortunately, they found what they were looking for: one red-coated dromedary, after going through a harrowing two-day labor, was so worn out she wanted nothing to do with a rare white colt that finally made his way out of her womb. The cameras capture the heartrending attempts that the colt (named Botok) makes at getting a drink of his mother’s milk. But snuggling up to his mommy’s belly is out of the question.

The weakling’s endeavors to catch up with Mom after she leaves him in the dust in spite of his moans of disappointment contrast with scenes of tenderness between the human mother and her children. Craving parental care is a good instinct God gave to both animals and people. Those who have experienced abandonment by a parent will instantly feel a bond with the unwanted colt. But this quirky docudrama speaks a more universal language: Who does not feel for a child abandoned by his mother?

The herders certainly do. In scenes that are partly a documentation of the unscripted young camel’s drama and partly re-enacted true-to-life situations, a hard-working, yurt-dwelling family of nomads playing themselves come to Botok’s defense. Young Odgoo (Odgerel Ayusch) and her husband, Ikchee (Ikhbayar Amgaabazar), send their two young sons on camels to the nearest village (about 30 miles away) to ask a violinist to accompany the animal mother and son into harmony.

As the two boys gallop away on camelback, leaving behind three generations of their ancestors in the tents they set up in the middle of nowhere, we witness the way globalization is inching its way even to the remote Mongolian settlement. The curiosity of the youngest boy, Ugna, guides the camera into a hut where children sit hypnotized in front of a TV with, incidentally, a cartoon that any child who grew up under Communism will recognize as the Russian Wolf and Hare, the saga of the stupid wolf and the hapless but fast hare. Later, the boy will ask his family for a TV set, and even though the grandpa will echo many American grandpas in saying that watching glass images is no good, his heart will be as soft toward his grandson as those of good grandfathers everywhere.

The satellite dishes, the motorcycles, the adidas hat Ugna wears on his trip, and even the batteries that the boys buy at the village store signal the unavoidable infringement of civilization on a lifestyle of simplicity and what we in the West view as inconvenience. But so far the modern inventions haven’t overtaken the cultural treasures of ritual and community.

In the local school, the two boys find a music teacher who agrees to play the Mongolian violin—an instrument that’s played like a cello but looks more like a banjo. Back at the steppe, the nomads gather for a worship ceremony to summon the blessing of the spirits, “remember that we are not the last generation on earth” and ask for forgiveness for their trespasses. The official faith of Mongolia is Tibetan Buddhist Lamaism, which dictates that people and animals live in harmony.

Once the violinist arrives from the village, the wooing of the mother camel begins. It is not surprising that the people who (along with their neighbors the Tuvans) brought us throat singing can harmonize so well with a haunting tune induced by a bow from two strings made from horse’s tail. Odgoo’s and the violin’s concert is soon amplified by the moans of the mother camel, who bats her long eyelashes as she deliberates whether to give in to the herders’ prayers and wishes. One waits with bated breath to see if indeed she will become the title’s weeping camel, whether she will repent and right the wrong she had done, leaving her witnesses wanting to do the same.

Talk About It

Discussion starters- Do you know anyone who has struggled with the idea of parenting—a young mother with post-partum depression, a woman who doesn’t want to have children because career comes first, a man who leaves his wife or girlfriend after fathering a child? What legitimate and illegitimate motives lie at the core of their behavior? How is God unlike the parents who abandon their children?

- Movies like The Story of the Weeping Camel remind us that the absence of modern trappings removes many temptations. When have you experienced simple living, without the distractions of a fast-paced Western culture? In those times, have you depended more on God than at other times, or has there been no difference? Why?

- What part of the movie moved you the most? Could you identify with any of the characters in the film at the time?

- The herders did not worship the Christian God. Do you think the one true God answered their prayers anyway? Or do you think the camel’s softened heart was just a response to the soothing power of music?

- Have you ever unjustifiably rejected a needy creature that depended on you—a human or animal? Has the Holy Spirit spoken to you about your action? Have you made up for it?

The Family Corner

For parents to considerThis movie is likely to arrest—and rest—the eyes of adults and children who are used to much faster editing in what they see. They do have to be able to read subtitles, which are typed in a relatively large font and change at a fairly slow pace. The movie’s content is pure. Some parents may decide that the labor scene, which shows the legs and head of the colt being born, may be difficult for younger children.

Photos © Copyright ThinkFilm

What Other Critics Are Saying

compiled by Jeffrey Overstreetfrom Film Forum, 07/22/04Last week, Film Forum featured reviews of The Story of the Weeping Camel. I have to lend my own applause to the roar of approval from other critics: This is one of the year’s finest films. Unfortunately, the film is only playing in a few theatres around the country. If the camels come to your town, don’t miss them.

from Film Forum, 09/02/04Denny Wayman and Hal Conklin (Cinema in Focus) say, “It is difficult to imagine all that has been lost as we have moved from the quiet depth of agrarian life, but it is clear that the relationships between family members and between humans and their animals has been injured by the change to modern life. It is a lesson the ‘weeping camel’ helps us remember.”

Copyright © 2004 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.