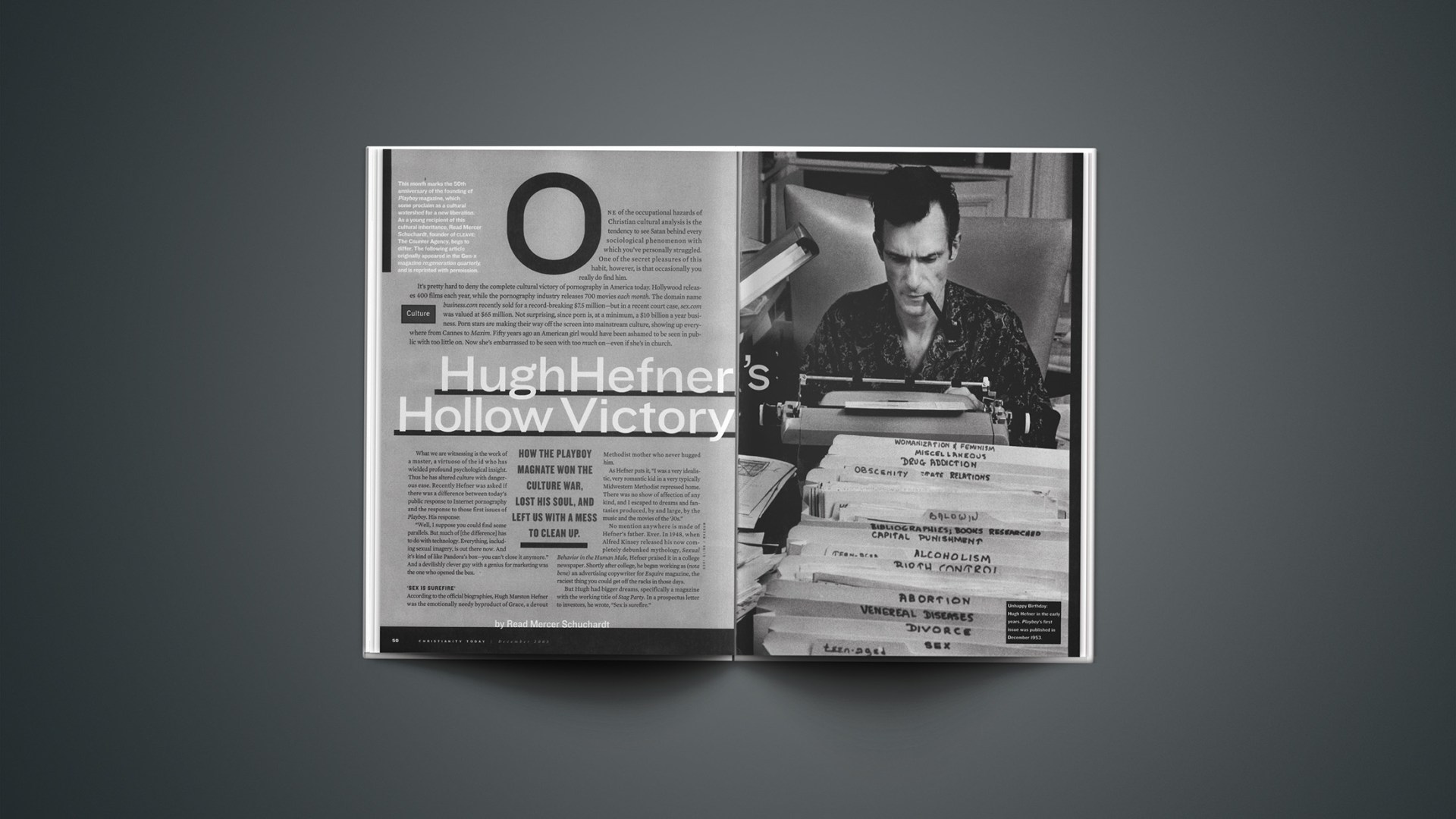

Editor’s note: This piece was published in 2003 for the 50th anniversary of the founding of Playboy magazine, which some proclaim as a cultural watershed for a new liberation. As a young recipient of this cultural inheritance, Read Mercer Schuchardt, now associate professor of communication at Wheaton College, begs to differ. The following article originally appeared in re:generation quarterly and is reprinted with permission

One of the occupational hazards of Christian cultural analysis is the tendency to see Satan behind every sociological phenomenon with which you've personally struggled. One of the secret pleasures of this habit, however, is that occasionally you really do find him.

It's pretty hard to deny the complete cultural victory of pornography in America today. Hollywood releases 400 films each year, while the pornography industry releases 700 movies each month. The domain name business.com recently sold for a record-breaking $7.5 million—but in a recent court case, sex.com was valued at $65 million. Not surprising, since porn is, at a minimum, a $10 billion a year business. Porn stars are making their way off the screen into mainstream culture, showing up everywhere from Cannes to Maxim. Fifty years ago an American girl would have been ashamed to be seen in public with too little on. Now she's embarrassed to be seen with too much on—even if she's in church.

What we are witnessing is the work of a master, a virtuoso of the id who has wielded profound psychological insight. Thus he has altered culture with dangerous ease. Recently Hefner was asked if there was a difference between today's public response to Internet pornography and the response to those first issues of Playboy. His response:

“Well, I suppose you could find some parallels. But much of [the difference] has to do with technology. Everything, including sexual imagery, is out there now. And it's kind of like Pandora's box—you can't close it anymore.” And a devilishly clever guy with a genius for marketing was the one who opened the box.

‘Sex is Surefire’

According to the official biographies, Hugh Marston Hefner was the emotionally needy byproduct of Grace, a devout Methodist mother who never hugged him.

As Hefner puts it, “I was a very idealistic, very romantic kid in a very typically Midwestern Methodist repressed home. There was no show of affection of any kind, and I escaped to dreams and fantasies produced, by and large, by the music and the movies of the '30s.”

No mention anywhere is made of Hefner's father. Ever. In 1948, when Alfred Kinsey released his now completely debunked mythology, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Hefner praised it in a college newspaper. Shortly after college, he began working as (nota bene) an advertising copywriter for Esquire magazine, the raciest thing you could get off the racks in those days.

But Hugh had bigger dreams, specifically a magazine with the working title of Stag Party. In a prospectus letter to investors, he wrote, “Sex is surefire.”

Like the budding advertising genius he was, Hefner already had the essence of his secret formula: the equation sex equals money. The Playboy.com FAQ puts it this way:

Why did [the first issue of Playboy] sell so well?

Largely because of its centerfold—a nude shot of Marilyn Monroe that Hef purchased from a local calendar printer.

Would Playboy sell so well if it didn't have naked women in it?

Probably not. We'll never know.

They'll never know because they'll never stop showing naked women, and it sells very well—Playboy has about 4.5 million “readers.” And yet this success couldn't be taken for granted when Hefner began. The photograph had been invented in 1839, and the word “pornographer” had entered the dictionary a mere 11 years later. Over the next 114 years, pornography was still very far from mainstream. The emerging soft porn carried the same stigma as the really dirty stuff, grainy black-and-white picture cards and stag reels made with old hookers and alcoholic johns. It was a vile business in an underground market. And because you had to show up to obtain it, participating in pornography meant publicly admitting that you were a pervert, even if only to a group of other perverts.

What pornography needed to be profitable on a mass scale was to be removed from the sexual ghetto and brought into the living room. It needed someone to adopt it, domesticate it, and teach it manners. As a mythmaker on the scale of Walt Disney, Hugh Hefner did for porn what Henry Higgins did for Eliza Doolittle.

As an adman, Hefner saw the need to package sexuality into aspirational categories, to tell a story about it that placed men in the narrative itself in a way that was not just acceptable but downright desirable. Thus he packaged himself as a Victorian gentleman at the hunting lodge.

Credit Hefner with popularizing the mythology that this was “adult” entertainment for “men,” adding the same aura of pseudo-sophistication that is still exploited 50 years later by bars that call themselves “A Gentleman's Club.”

“In launching Playboy, perhaps the smartest thing Hugh Hefner did was in establishing his personality as that of a witty, urbane sophisticate who enjoyed the company of many, many young women,” writes Tim Carvell on McSweeneys.net. “After all, who knows how many fewer copies the magazine might have sold, had he instead depicted himself as a solitary masturbator?”

Later, when Playboy started to succeed financially, Hefner further gentrified the perception of sexuality by hiring writers like Norman Mailer and John Updike to offer intellectual essays on the cultured life.

Hefner's medium also reinforced his message. Compared to other transmission models of the time, Playboy had several distinct advantages. First, it could be easily purchased or subscribed to—and thus enjoyed privately in the home. Second, it was positioned as a mass-market magazine—communicating in one stroke the idea that commercialized sex was acceptable in mainstream America. Third, it could attract advertisers for upscale products that had nothing to do with sex, except as an accessory to creating the ultimate bachelor's pad. Advertising was not merely a revenue stream for Playboy; by surrounding his pinups with sophisticated products, Hefner clothed the nudity in one more layer of legitimacy.

As one critic put it, “‘The 'brilliance’ of Playboy was that it combined the commodification of sex with the sexualization of commodities.”

Contra the critics

For all his brilliance, it's worth noting that Hefner didn't actually have the guts to put his name anywhere in the first issue. Quoth the Playboy.com FAQ: “If the magazine failed, he felt it would be easier to find another job in the industry.” In the era of blacklisting, he wanted to duck any moral outrage that came his way.

But he needn't have worried. Hefner's strategy included this brilliant Catch-22: any expression of moral outrage about Playboy would entail the admission that you had seen it. If it was so morally objectionable, why were you looking at it?

This is still the main reason that Christians of all stripes ignore or deny any knowledge of pornography, when it is believers who should be the most willing to discuss the glory and grandeur of sex as God designed it. Following Hefner's cue, apologists for the porn industry today love nothing more than pointing out the hypocrisy of expressing moral outrage about porn while so many—including many of the critics—are simultaneously consuming it. If everyone's secretly doing it, Hefner argued, why be so prudish and puritanical about it? Bring it out into the open and you'll feel a lot better.

Hefner also had the foresight to defeat his critics by seeming to engage them seriously. Compared to today's PR tactics of avoidance and denial, Playboy back then was genuinely intellectual if not intellectually honest. In the first installment of the “Playboy Philosophy” column, Hefner quoted his religious critics, among them Unitarian minister John A. Crane, who wrote:

It strikes me that Playboy is a religious magazine, though I will admit I have peculiar understanding of the meaning of the word. What I mean is that the magazine tells its readers how to get into heaven. It tells them what is important in life, delineates an ethics for them, tells them how to relate to others, tells them what to lavish their attention and energy upon, gives them a model of a kind of person to be. It expresses a consistent worldview, a system of values, a philosophical outlook.

Not only does Playboy create a new image of the ideal man, it also creates a slick little universe all its own, creates what you might call an alternative version of reality in which men may live in their minds. It's a light and jolly kind of universe, a world in which a man can be forever carefree, like Peter Pan, a boy forever and ever. There are no nagging demands and responsibilities, no complexities or complications.

Today, of course, this “alternative version of reality” is the world we live in. Hefner countered and absorbed his critics by going on for another 10 years in a never-ending series of installments, complete with footnotes and indexes, that gave the illusion of a genuine dialogue—as if he too cared about the moral soul of the culture. There was even a series of in-depth discussions with leading theologians and thinkers discussing the “historical link between sex and religion.” Granted, these discussions raised some valid points. But at their conclusion, Rabbi Marc Tanenbaum offered a summary that inadvertently illustrated the defeat of the religious establishment.

“We are dealing with new realities and our problem, as conscientious members of the religious community, is to try and decide to what extent our classic positions must be changed to accommodate the new realities—to what extent are we trying to impose the classic positions on contemporary society in an attempt to get it to conform more to what we have regarded in the past as the good, the true, and the beautiful.”

This turns the matter exactly upside down: what was really happening was that Hefner was imposing his new standards on society, making us conform to his new ideas of goodness, truth, and beauty.

Sexual revolution for whom?

If you're younger than 40, you might mistake Hefner's topsy-turvy world for normal, since it's the world you were born into. Hefner succeeded at inverting traditional sex roles.

First Hefner took men out of the field and stream and into the living room. As Chris Colin of Salon says, "The Playboy universe encouraged appreciation of the 'finer things'—literature, a good pipe, a cashmere pullover, a beautiful lady. America was seeing the advent of the urban single male who, lest his subversive departure from domestic norms suggest homosexuality, was now enjoying new photos of nude women every month.”

Key to this extension of bachelorhood was the need to fend off any suspicion of homosexuality, something Playboy and pornography have had in common since their inception. The supply and demand for pornography, after all, is overwhelmingly from men to men. As the porn star Annabel Chong said in Harper's magazine of her World's Biggest Gang Bang, “It's a very homoerotic thing… . I'm just there to guarantee the heterosexuality of it all.”

Thanks largely to Hefner's pioneering spirit, where women are free and equal, they are free and equal to be as promiscuous as men. Just go shopping at The Gap or pick up any women's magazine published in the last few decades. In it you will find an article, essay, or questionnaire demonstrating or demanding that women should have more sex than they are having. Is there an escape, a way out, a means by which a woman can choose not to have her social norms and sexual drives dictated by porn culture?

The Playboy philosophy, which requires women to be thin, infertile, and always available, essentially requires childlessness. And you can bet your birth control packet that abortion is the natural bedfellow of the successful playboy.

The Playboy Foundation, the (ahem) philanthropic wing of Playboy Enterprises, provides grants and donations to a wide range of projects, most involving reproductive rights and freedom of speech—industry code for promoting sexual license as a natural right, and abortion as a failsafe guarantee. Hence the heavy support of the ACLU, Planned Parenthood, NARAL Pro-Choice America, and similarly single-minded organizations.

Of course, Hugh Hefner is on the side of women's liberation—as long as it supports his “incredible machine that brings to me the most beautiful young women … already wanting to be … part of my life.” What could be better for an irresponsible and sexually aggressive male than an entire culture that considers women sex objects, treats pregnancy as a disease, and offers abortion as its cure?

Just ask Hefner himself. Here he is, in the first issue of Playboy, telling real women where to go: “We want to make it clear from the very start, we aren't a ‘family magazine.’ If you're somebody's sister, wife or mother-in-law and picked us up by mistake, please pass us along to the man in your life and get back to your Ladies Home Companion.”

This is the boys club, in other words, and you girls are not allowed.

So when Hefner says, “The major beneficiary of the sexual revolution is women, not men,” you're right to be scratching your head in confusion. Porn culture demands of women precisely what real women don't need or want: skinny bodies, huge fake breasts, no babies, and men who are unwilling to commit to anything more than a quick shag.

In a Vanity Fair cover story last March, Hefner exclaimed, “But here's the surprise—this is what they want.” If this is really what they want, why would the Playboy.com FAQ state that the average Playmate's fourth-highest ambition is “having a family”?

What softcore?

Until July 2001, Hefner could claim that he never pushed the envelope into harder or grittier pornography—a word that Playboy always resisted for its own wares. But without Hefner's initial timorous first step, which met with so little resistance, there would have been no Larry Flynt, Bob Guccione, or any of the others who pushed sex to the outer limit of acceptability, a limit that now changes almost hourly.

Playboy, once so proud of its “gentleman's” standards, has embraced the outer boundaries of what it once found to be, well, pornographic. In July 2001 it acquired three x-rated sex channels from Vivid Video, one of the largest producers of porn movies. Playboy Enterprises is now the dominant economic force in pornographic television programming.

And all of this has happened through a few reliable tricks of the trade that go right back to the serpent in the garden, who played the first game of “two truths and a lie.” Most every temptation proceeds by offering almost the whole truth. The woman in the garden was promised that her eyes would be opened, that she would be like God, and that she would know good from evil. The serpent delivered—almost. Her eyes were opened; she did know good from evil. But she did not become like God.

Hefner, too, can deliver on two of his three promises. Women, he purrs, are the refined gentleman's path to truth, goodness, and beauty. Hefner certainly did—and does—deliver beauty, albeit a two-dimensional version. And in the early days at least, his women were the good, clean, “wholesome” type that men might aspire to romantic involvement with—certainly far more so than anything pornography had previously offered (unless you count the pre-Raphaelites and Le Dejeuner sur L'Herbe).

But Hefner does not deliver truth. Bring it out in the open, Hefner said, and you'll feel better. Well, like it or not, the Playboy philosophy is now your culture's philosophy. Do you feel better?

Hefner's Playmates—and, in the culture he has done so much to shape, all women—are primarily visual objects, metaphysically truncated to their improbable physical attributes. Among the consequences: all female rock stars are now obliged to be beautiful, contributing to a dearth of quality female vocalists—not because women can't sing, but because pornographic culture won't allow any but the most beautiful women to get on the stage.

The same is true for women newscasters and waitresses, but the irony is doubly poignant in the music industry, where the melodious sound of someone's voice may never get to your ears because she lacks the visual appeal required by mass marketing.

Sexually Stunted

Hiding in plain sight in the June 2001 issue of Philadelphia magazine is Ben Wallace's essay “The Prodigy and the Playmate.” In it Sandy Bentley, the Playboy cover girl and former Hefner girlfriend (along with her twin sister Mandy), describes Hefner's current sexual practices in just enough detail to give you a good long pause:

“The heterosexual icon [Hugh Hefner] … had trouble finding satisfaction through intercourse; instead, he liked the girls to pleasure each other while he masturbated and watched gay porn.”

This statement may seem either shocking or trivial. But it points to that which Hefner's detractors have been saying for years: Pornography stifles the development of genuine human relationships. Pornography is a manifestation of arrested development. Pornography reduces spiritual desire to Newtonian mechanics. Pornography, indulged long enough, hollows out sex to the point where even the horniest old goat is unable to physically enjoy the bodies of nubile young females.

Ultimately, Hugh Hefner is an old joke: a solitary master baiter. Armed with two-thirds of the truth and a well-lubricated marketing machine, he has played a large role in manipulating society into accepting his adolescent fantasy of false desire and technological gratification—a legacy that amounts to our generation's toxic dump.

And, now in his late 70s, it's unlikely that Hefner will ever grow out of his self-serving, adolescent phase. You and I will have to wipe up his mess.

Read Mercer Schuchardt is the founder of CLEAVE: The Counter Agency.

Copyright © 2003 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

Schuchardt earlier wrote about the effects of pornography for Breakpoint Online.

See more of Schuchardt's work at Cleave.com.

Other CT articles on pornography include:

Tangled in the Worst of the Web | What Internet porn did to one pastor, his wife, his ministry, their life. (Feb. 23, 2001)

Resources for the Ensnared | Christ-centered help for those struggling with Internet pornography and sexual addiction. (Feb. 23, 2001)

We've Got Porn | Online smut is taking its toll on Christians. What is the church doing about it?(July 5, 2000)

Internet Pornography Use Common in many Libraries, Report Says | Librarian-researcher claims American Library Association thwarted study. (March 20 , 2000)

Christian Singer Shares Struggles with Pornography | Secret sin of Clay Crosse's youth reappears in midst of ministry (Feb. 7, 2000)

Amazon.com Pulls Book Targeted as 'Kiddie Porn' | But critics say other pedophilia books are still offered. (Jan. 24 , 2000)

Smut Magazine Publishers Convert | (April 26, 1999)

Curbing Smut Legally | Tough ordinances shut down porn outlets. (Feb. 8, 1999)

Christian Leaders Target Cyberporn | (Jan. 6, 1997)

Advice and experience from Leadership magazine:

Hooked | First he turned on the computer, then the computer turned on him. (Winter 2001)

Alone with my lust | Until my pastor held me accountable. (Summer 1996)

The War Within Continues | An update on a Christian leader's struggle with lust. (Fall 1988)

Battle Strategy: Some Practical Advice | An update on a Christian leader's struggle with lust.(Fall 1982)