In november of last year George Barna came home disheartened. He had been on the road for most of 2001, giving all-day seminars in 54 cities to pastors and church leaders. Barna, who is 47 and has large, soulful eyes, is to evangelicals what George Gallup is to the larger culture. Pastors frequently cite his statistical findings in sermons, and his many books about church ministry sell consistently. For the past six years he has been keeping a fierce pace, spending more than half his time away from home (he always travels with his wife and two small children). He is an intensely introverted personality who dislikes public speaking. Something apart from road weariness discouraged him, however.

“Increasingly the question was emerging: I can keep doing all this, and probably make a living for a long time, but so what? Ultimately I stand before a holy and righteous God who placed me here to serve him with the gifts and vision that he entrusted to me. He’s going to ask, ‘What did you do?’ . …I can’t imagine standing before him and saying, ‘Well, I sold out. I knew that what I was doing didn’t work, but it would have been too big, too hard to do something different. I didn’t want to admit that what I thought might work had failed.’ ” An expert pollster and market researcher, Barna prides himself on realism. Sometimes he angers people with his apparent pessimism, but the truth must be faced, he believes. God had called Barna “to serve as a catalyst for moral and spiritual revolution in America.” He had hoped to push church leaders to revitalize the church, to make it as beautiful and powerful as God meant it to be. His ten-year campaign had failed.

“The strategy was flawed because it had an assumption. The assumption was that the people in leadership are actually leaders. [I thought] all I need to do is give them the right information and they can draw the right conclusions . …Most people who are in positions of leadership in local churches aren’t leaders. They’re great people, but they’re not really leaders.”

With that chilling assessment Barna changed his course. He’s not about to quit—he believes with all his heart in God’s calling to “moral and spiritual revolution.” He has concluded it won’t happen in this decade, though. He’s now beginning to chart a course that looks 20 to 30 years ahead for results.

More Than Selling Kleenex

Barna grew up in Princeton, New Jersey, a cradle Catholic who went to Mass daily when he started college at Washington and Lee University. After finishing at Boston College, where he majored in sociology with a minor in religion, he went to work on the campaign staff of a Boston politician. Idealism attracted him to politics but soon caused his disenchantment. His liberal Democrat boss cared about people, Barna was delighted to learn. But when his boss wanted to “solve” a messy pregnancy by arranging an abortion, Barna quit, one month before the primary election.

Shaking the dust of politics from his feet, Barna went to graduate school. Beginning at Rutgers University in urban planning, he grew interested in political polling and ended up earning a second M.A. in political science. Meanwhile, he had married his hometown girl, and together they began what they referred to as their search for God.

The way Barna describes it, neither one of them knew much about religion outside of their native Catholicism. It wasn’t working for them, they concluded, but nevertheless they believed in God and talked often of their search for him. Eventually their pilgrimage led them to a small, fundamentalist Baptist church. The pastor, a Bob Jones University graduate, introduced them to Bible study and a personal relationship with God. Unfortunately, he also ushered them out of the church within a few short months, because he demanded that the newly converted Barna shave his beard and cut his hair.

Despite that confusing beginning, something momentous had happened to the Barnas. Upon graduation George took a job with a media research firm in Los Angeles. His new employers put him on an account working with televangelists Rex Humbard and Oral Roberts. To Barna, “Oral Roberts” was a basketball team. The first time he watched an Oral Roberts television special, “words of knowledge” and faith healing utterly confounded him. He loved working for a Christian cause, however, and soon quit his secular job to work for a Christian media company headquartered in Wheaton, Illinois. “I loved the people, loved the ability to get out of bed in the morning and do something [more significant than] another ad to sell Kleenex.” The work involved fundraising campaigns, which for Barna “wasn’t even about raising money” in itself but about “knowing that there’s money there to see a kid’s life changed” and “alerting a constituency to the potential to use the resources that God has given them to good ends.”

Marketing the Church?

The Barnas tried dozens of churches in Southern California and later in Wheaton, coming away unsatisfied until they visited an upstart congregation in the Chicago suburbs known as Willow Creek. The church, led by Bill Hybels, sought to communicate the gospel on seekers’ terms, even if that meant abandoning some church traditions. It was dynamic and savvy. Its leaders seemed to apply good marketing strategy to church life, in just the way that Barna had learned to apply it to television or fundraising. “That gave us a whole new understanding of what the local church could be,” he says.

In 1984 Barna moved back to Southern California to launch his own company, Barna Research. He intended to offer his research and marketing expertise as a service to Christian ministry.

Jim Engel, who taught marketing at Wheaton Graduate School and Eastern College, says that Barna “does very good work, and his work can be trusted. He is a very competent researcher, and he has integrity.” Similarly, pollster George Gallup says that Barna has “a really good research mind.”

Market research does, however, see the world from a particular angle, which is both Barna’s strength and his blind spot. Marketing begins by analyzing the target audience and trying to understand what communicates effectively. As Leadership Network’s Carol Childress points out, good missionary anthropology offers many parallel insights. How do we reach a particular group of people with our message and draw them into appropriate action? For example, if you learn that your target audience finds church robes repellent, you will consider other clothes. If movies are a fount of meaning for your audience, you will bring movies into your message.

Market research is not a neutral tool, however. It grew as a business technique, and reflects some of the biases of business. While missionary anthropology knows a lot about spontaneous revivals, business focuses on planned action: strategy, market segmentation, and communication techniques. While acknowledging the unplanned and unexpected, business concentrates on what it can control. Market research thus tends to project a closed system where every action has a consequence, and mysteries are rare. Some refer to this approach as “scientific,” but genuine science leaves plenty of room for the awe and mystery at the center of things. Market research rarely inspires wonder.

It does, however, inspire innovation and action. It wants results and is impatient with excuses. It thinks hard about culture and communication, and it works hard to stay abreast of change. In an offhand reflection on his frustration with the American church, Barna says, “We’re spending $50 to $60 billion a year on domestic ministry. Tell you what—you give the ceo of ibm $50 to $60 billion this year, and see what he can do.” Whatever the shortcomings of that perspective, it has the strength of boldness. It’s willing to consider total reorientation for the sake of effectiveness. What’s more, market research offers useful ways of evaluating possible action, and testing whether current programs have their intended effect.

You cannot understand George Barna’s analysis of the American church without grasping that marketing forms its essential grid—as, indeed, it forms the essential grid for much of American evangelicalism. When Barna first heard fundamentalist Bible teaching during his graduate student years, he told his wife with great excitement, “That, I really believe, is marketable!” A market research mindset was also implicit in his reasons for leaving the Catholic Church: “They’re saying don’t you dare question it.” Market research leaves no place for authority; it assumes everything can be taken apart and analyzed.

In 1988 Barna published Marketing the Church, his second book. From his point of view it was noncontroversial, urging churches to do their best to communicate the gospel effectively. Some critics reacted strongly, however, as though the title was equivalent to “selling the church.” They understood marketing as pandering, watering down the message, accommodating the gospel to the “felt needs” of sinful people. Barna was blindsided by the criticism. “It shocked me; it depressed me; it hurt me,” he says. “The intensity of the anger really surprised me.”

That kind of criticism has diminished. Nowadays most pastors probably accept marketing as a means to effective communication, something all good communicators do, consciously or not. When Barna says that Jesus used marketing, he probably still causes hair to stand up on many necks, but he merely means that Jesus geared his communication to the capacity of his audience. That’s not in dispute.

Nevertheless, some people believe the marketing mindset has serious shortcomings. In a forthcoming book, Habits of the High-Tech Heart (Baker, 2002), Calvin College’s communications professor Quentin Schultze writes: “Information technologies foster statistical ways of perceiving and systematic modes of imagining. … a closed system that elevates the value of control over moral responsibility . …We imagine cultures not as organic ways of life, but instead as computer-like networks—closed systems that persons can objectively observe, measure, manipulate and eventually control.”

In short, the view is only a slice of reality, and overrates the possibility of human control. Schultze quotes Václav Havel, the president of the Czech Republic: “The feeling that ‘if nothing is happening, nothing is happening’ is the prejudice of a superficial, dependent, and hollow spirit, one that has succumbed to the age and can prove its own excellence only by the quantity of pseudo-events it is constantly organizing, like a bee, to that end.”

That is a bit strong. Coming from one of the leaders of a genuine revolution, however, it makes this point at least: When “nothing is happening,” a great deal may be happening. Market research has no way to measure that. It happily evaluates a Billy Graham crusade because that is a planned activity with articulated aims. It cannot tell you, however, where and how the next Billy Graham will appear. Nor can its imagination fathom Antony of the Desert (also known as Antony of Egypt)—who inspired the monastic movement when he went into the desert to pray—and thus changed the course of European history.

Turning Down Disney

Within weeks of starting Barna Research in a bedroom of his home, Barna got a call from an old colleague. A vice president with the Disney Channel, she offered him a contract to do market research. For the next seven years, Disney offered steady, profitable work that kept the company afloat to do Christian ministry. Ironically, considering “all the flak that Disney gets from the Christian community,” Barna says, “Disney built Barna Research.”

By 1991, however, Disney had begun to pressure Barna to give its business his full attention. At the same time, Barna’s research was painting a discouraging picture of the church. “There was just such a radical gap between what we heard Christians professing they believed and the values and the lifestyle that grew out of the values,” Barna says.

Marriages, for example, were as likely to come unglued for believers as for unbelievers. Churchgoers didn’t seem to have any real understanding of the Bible’s distinctive message; many practicing Christians believed that the Bible teaches that “God helps those who help themselves.” A morally relativistic American culture was shaping Christians more than Christians were shaping the culture.

More frustrating yet, churches seemed barely aware of the problem. “You go talk to pastors, and hear them talk about all the programs and all the numbers and the money and all the buildings,” Barna says. “But you almost never hear them talk about how the lives of their people were so demonstratively different that people had to pay attention to the cause of Christ and take it seriously.”

Marketing is Barna’s grid, his way of seeing, but Barna goes beyond bloodless research and analysis. He never seems to forget his own plight, when he was searching blindly for God despite the scores of churches in his neighborhood. “I got to the point where I realized we cannot be a place that provides information to ministries and says good luck,” he says. “We’ve got to help them take it to the next step, because most of the information users in ministries don’t know how to use information. We kill ourselves to give them good information, good research, and they nod their heads approvingly and then they don’t do anything with it. Disney, we give them the information and the next day they’ve got a policy; they’ve got a program; they’ve got something to convert that into practical action.”

Barna spent much of a Hawaiian vacation in 1991 praying about the direction of his company. He considered dropping ministry research and focusing on Disney, but then, “For the first time in my life I heard the Lord clearly speak to me, no doubt. ‘George, you idiot, do you really believe I’ve allowed that funky little company of yours to exist all this time, building up contacts in the Christian world, building up your facilities, being profitable, understanding things about the church, only to turn your back on my church because they’re tough to work with? Go back and read the Old Testament.’ ” When he returned to California, Barna cut ties with Disney and began to concentrate all his energies on a campaign to change the church.

His plan for the church was summed up in his next three books. The first was The Frog in the Kettle (Regal, 1990). The title image is the familiar story of the frog that doesn’t react as the kettle gradually heats to boiling. Barna tried to impart dramatic urgency to the church: change or die!

Another book, User Friendly Churches (Regal, 1991), told about the qualities he observed in the several thousand American churches he considers healthy and vital. It’s not that they are all identical, nor that they form a blueprint for everybody, but that they serve as inspirational examples.

In 1992 came The Power of Vision (Regal), a departure from Barna’s usual presentation of statistics. The business world had made vision a catchword, and during his Hawaiian vacation Barna realized that he lacked vision for himself. By vision Barna means a burning call to a specific ministry: not evangelism in general but, for example, outreach to truck drivers through truck-stop chapels. “Vision is specific, detailed, customized, distinctive and unique to a given church,” he writes. At Willow Creek he had experienced the difference that a clear, articulated vision could make, but most church leaders only seemed to grasp for a program that “worked.” Vision comes from God, Barna was sure, and church leaders need to actively seek it.

Bad News for the Church

Barna does not have a script for the American church. He admires some megachurches but doesn’t think the future necessarily lies with them. Each leader or team of leaders must discover their own vision, Barna thinks. He emphatically does not believe that polling can give it to them.

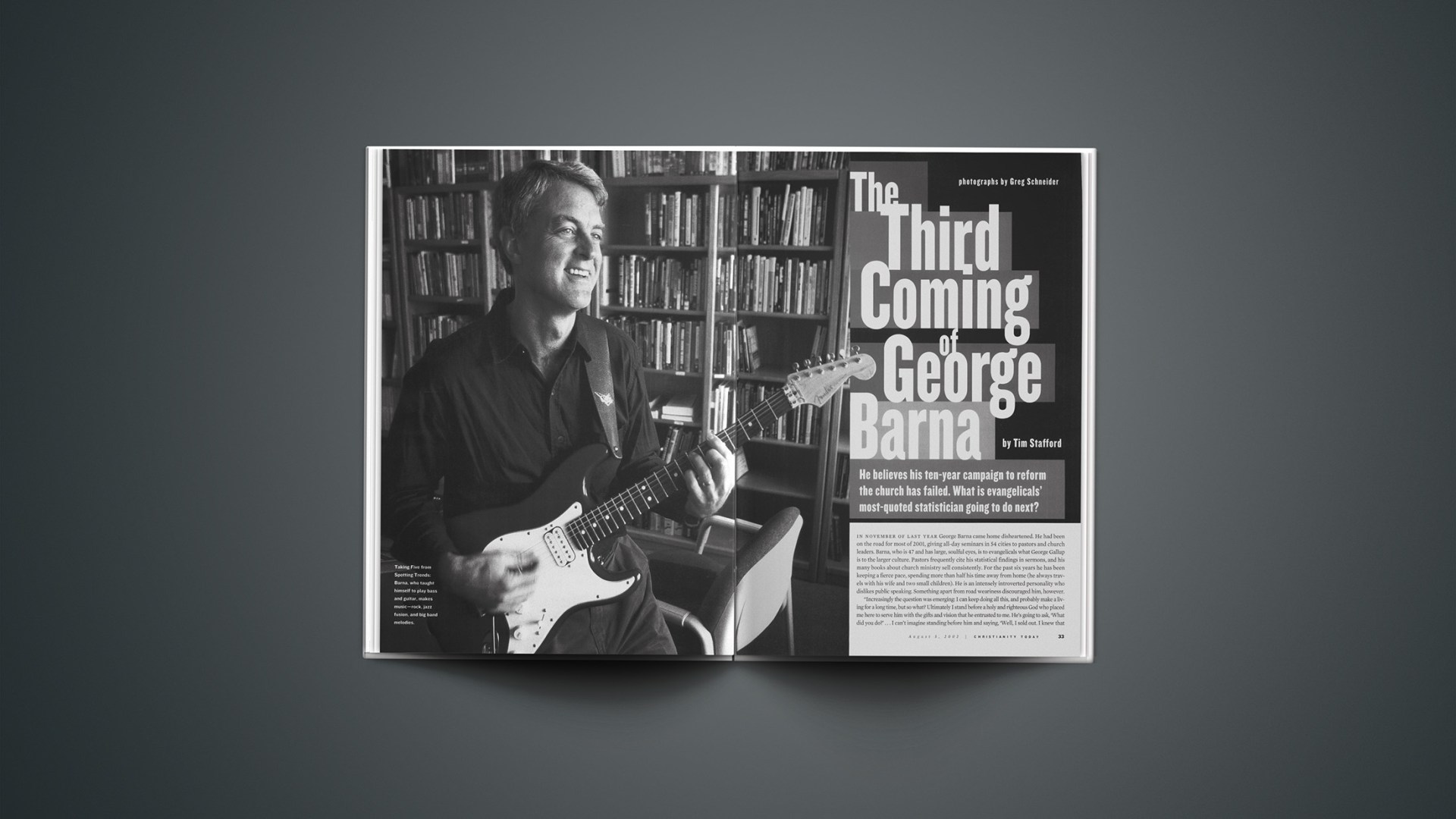

Throwing himself into his crusade to change the church, Barna began a grueling schedule of all-day seminars. In addition to his seminars and continuing research, he wrote books, consulted with churches, and launched a website (www.barna.org). To learn more, he served on the staff of a church—a short-lived experiment as executive pastor and later teaching pastor—and helped to launch another church, an attempt that ultimately failed.

Barna thought that by impressing on church leaders the urgency of the situation, by providing them with hopeful models, and by imploring them to find God’s vision for their own ministries, he could surely mobilize at least part of the church. All such hopes came crashing down last November, when he concluded that his strategy was flawed and that he had failed.

In 1998 George Barna published what he considers his most important book, The Second Coming of the Church. It offered the most dramatic ultimatum yet: “At the risk of sounding like an alarmist, I believe the Church in America has no more than five years—perhaps even less—to turn itself around and begin to affect the culture, rather than be affected by it. Because. … our central moral and spiritual trends are engulfed in a downward spiral, we have no more than a half-decade to turn things around.”

Before the five years were up, Barna knew the answer. “Nothing’s changing, and the change that we see is not for the better,” he says. His constant surveying of the American public reveals no turning back from moral and spiritual relativism.

The aftermath of September 11 settled it for him. He had thought perhaps it would take persecution or war to shock America into spiritual reflection. As a traumatized nation streamed into churches, the church had a moment of opportunity. “The sad outcome is that when we needed great leadership, we didn’t have any guts,” he says. “That moment of opportunity was squandered.”

It’s not really courage that Barna identifies as crucial, though. He’s spent untold hours interacting with pastors and church leaders, and he’s convinced that the majority of them aren’t leaders. Most are admirable people whose gifts lie in Bible teaching or pastoring. Those are valuable gifts, Barna affirms, but they are not leadership. By leadership he means the ability to motivate and lead institutional change.

Barna found that those who attended his seminars didn’t come back when he visited their city a second time. “If you’re not a leader and you hear this stuff, it’s incredibly threatening, depressing, and unproductive. Because it gets interpreted through the lens of ‘I’m a failure.’ That’s not what I’m saying. A lot of pastors don’t want to have anything to do with me, because they think I’m against them. I’m not against them. I’m not saying they shouldn’t be in the ministry. I’m saying they need to understand what God designed them to do in ministry, and not try to do something that God didn’t call them to be.”

One might question Barna’s analysis. Drawn from the business world, it assumes an entrepreneurial model of the church, which requires a certain kind of leadership. “Once pastoring meant shepherding,” says Leadership journal editor Marshall Shelley, “knowing your people by name, being able to inquire as to their spiritual condition, being involved in the cure of souls.” He says church history makes him doubt “we’re a step and a half away from extinction.”

“The church is amazingly resilient,” he says. “Think of the Soviet Union, think of China, think of Africa. Spiritual vitality is not going to become extinct just because we don’t have a certain kind of leader. The evidence is overwhelming on the other side. We have the privilege of cooperating with an irresistible force in God’s grace.”

The sheer logic of Barna’s position is hard to refute, though, so long as you accept his terms. Taking a marketing mindset to its logical end, the conclusion for American Christianity is drastic. A business that can’t sell its product has to change its approach. If it won’t or can’t, it’s dead.

Search for a New Strategy

George Barna is not a quitter. He is tenacious, determined, and focused. We live in a world of rapid change, he says, and most churches don’t have the capacity to adapt. Having concluded that today’s church can’t make a difference, his next question is, What can?

He’s doing research to identify the top influences on Americans’ lives. He already knows the church isn’t on the list. Movies, TV, contemporary music, the Internet, books, parents, and politicians are. In the short term, he’s looking for ways to affect what he calls the SSI, or Strategic Sources of Influence. In the long run, he hopes to cultivate a new generation of leaders, locating them as early as high school and challenging them to participate in strategic development of their capacities to lead for Christ. Twenty or 30 years from now, he hopes to see the result in a healthy, dynamic church.

While he carries on research, he is exploring new strategies. He’s been visiting “key leaders” (mostly heads of parachurch ministries, to judge by those he names) to find allies for the next step. He’s realized he cannot do it alone, so he’s looking for partners who share his passion and anguish.

Again and again Barna returns to Acts 2, with its description of the vitality of the early church in Jerusalem. He’s captivated by that elemental account of a church beginning to change the world.

However, he identifies less with Peter and Paul than he does with Jeremiah and John the Baptist. Of all the biblical characters, “I resonate with them,” he says. “I feel their pain.”

It may seem odd to think of a prophet wielding numbers from market research. Yet one has the sense that truth would burn inside Barna, as it did with Jeremiah, whatever his training and career.

There’s plenty of room to criticize his way of analyzing the church. He has restricted vision, and his definition of a church leader seems very demanding. Yet he unmistakably has a vision, a strong commitment that longs to see the American church transform our society, and grieves that it has not. It bothers him deeply that the church is soft, and possesses no urgency to change. Like most prophetic types, Barna is consumed by his vision and, likewise, sees little fruit to his labor.

Tim Stafford is a senior writer for Christianity Today.

Copyright © 2002 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

A ready-to-download Bible Study on this article is available at ChristianBibleStudies.com. These unique Bible studies use articles from current issues of Christianity Today to prompt thought-provoking discussions in adult Sunday school classes or small groups.

Also appearing on our site today:

Barna’s Beefs – His nine challenges for American Christianity—prophetic words, or sweeping generalizations?

The official site of Barna Research includes research archives, ministry resources, and more information.

Barna’s The Second Coming of The Church, User Friendly Churches, The Power of Vision, Boiling Point, and The Habits of Highly Effective Churches are available at Christianbook.com. Frog in the Kettle is available at Amazon.com.

Reviews of Barna’s books in Christianity Today sister publications include:

Barna’s Kettle is BubblingAfter ten years, this frog is well done. (Leadership Journal, Spring 2001)

Barna & BaileyThe Greatest Research Show on Earth? (Books & Culture, May 22, 2000)

Christianity Today articles about Willow Creek Community Church include:

Willow Creek’s Place in HistoryIt turns out that the church that made “seeker-sensitive” a part of our vocabulary is not as revolutionary as its critics have said. (Nov. 7, 2000)

The Man Behind the MegachurchThere would be no Willow Creek—no small groups, no women in leadership, no passion for service—without Gilbert Bilezikian. (Nov. 6, 2000)

Community Is Their Middle NameAs Willow Creek Community Church turns 25, it is bigger than ever, drawing 17,000 a weekend. But what really makes Willow tick is what comes after the seeker services. (Nov. 3, 2000)

Recent articles by Tim Stafford include:

How to Build Homes Without Putting Up WallsHabitat for Humanity strives to keep its Christian identity—a tricky task, when everybody wants to join. (May 31, 2002)

Whatever Happened to Christian History?Evangelical historians have finally earned the respect of the secular academy. A few critics say they’ve lost their Christian vision. Hardly. (March 22, 2001)

The First Black Liberation Movement | The untold story of the freed slaves who brought Christ—and liberty— to West Africa. An interview with Lamin Sanneh (July 14, 2000)

Taking Back FresnoWorking together, churches are breathing new life into a decaying California city. By Tim Stafford (Mar. 10, 2000)

CT Classic: Ron Sider’s Unsettling Crusade | Why does this man irritate so many people? (originally published Apr. 27, 1992; posted online Mar. 13, 2000)

How God Won When Politics FailedLearning from the abolitionists during a time of political discouragement. (Jan. 28, 2000)

CT Classic: Bethlehem on a BudgetPlanning a church budget and the Christmas story share surprising similarities (originally published Dec. 15, 1989; posted online Dec. 23, 1999)

The Business of the KingdomManagement guru Peter Drucker thinks the future of America is in the hands of churches (Nov. 8, 1999)

Anatomy of a GiverAmerican Christians are the nation’s most generous givers, but we aren’t exactly sacrificing. (May 19, 1997)

God’s Green Acres | How DeWitt is helping Dunn, Wisconsin, reflect the glory of God’s good creation. (June 15, 1998)

God Is in the BlueprintsOur deepest beliefs are reflected in the ways we construct our houses of worship. (Sept. 7, 1998)

The New TheologiansThese top scholars are believers who want to speak to the church (Feb. 8, 1999)

The Criminologist Who Discovered ChurchesPolitical scientist John DiIulio followed the data to see what would save America’s urban youth. (June 14, 1999)